THE ELUSIVE ARYANS: Who were they and where did they come from?

The Cradle of Indo-EuropeansThe dawn of Indo-Europeans on the Ukrainian steppes

|

|

The rise of the Trypillian culture on the right bank of the Dnieper 7,000 years ago overshadowed the birth of Indo-European peoples on its left bank. The Indo-Europeans were a group of around 200 related peoples that inhabited Europe and Western Asia from India to Great Britain and the Pyrenees. They created the European civilizations whose cultural accomplishments contributed greatly to the progress of humankind over the past centuries.

In April 1786, Sir William Jones, a polyglot and a Supreme Court judge in Calcutta, India, made a great discovery. When reading Rigveda, a compilation of sacral hymns of the Aryan conquerors of India, he found that the predecessors of modern Indo-European languages, including Sanskrit, Latin, Ancient Greek, Germanic and Slavic languages, were related.

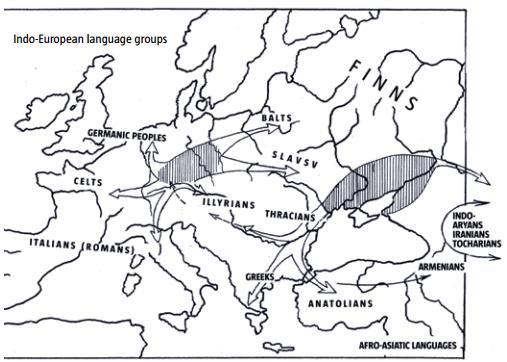

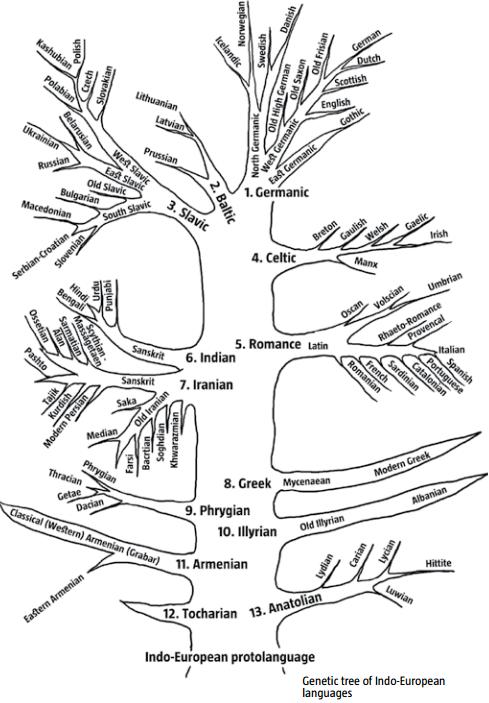

19th-century linguists – most of them German – took up his cause, developing comparative linguistic analyses and proving that Indo-European languages shared a common origin. Their research resulted in a classification of Indo-European languages comprised of 13 ethno-linguistic groups, including Anatolian, Indian, Iranian, Greek, Italian, Celtic, Illyrian, Phrygian, Armenian, Tocharian, Germanic, Baltic and Slavic.

READ ALSO: Terra Sudorum

According to researchers, all of these languages are closely related because they developed from the Indo-European protolanguage – a common ancestor. The next challenge was to find the territory where its speakers lived and trace their migration that began in the 4th millennium B.C.

In pursuit of a homeland

The search for the Indo-European proto-homeland has a dramatic history spanning two centuries. Following William Jones’ discovery, India was declared the proto-homeland and Sanskrit from Rigveda was interpreted as the origin of all languages, arguably preserving all features of the proto-language. According to the common belief at that time, the favourable climate of Hindustan enabled demographic booms and caused migration westward to Europe and Western Asia from the overpopulated subcontinent.

Soon, however, it turned out that the language in the Iranian Avesta was nearly as old as the Sanskrit in Rigveda. Thus, the common ancestor of all Indo-European peoples could have lived in Iran or somewhere in the Middle East where important archaeological discoveries were being made at that time.

In the 1830-1850s, researchers thought that the Indo-Europeans had come from Central Asia, then considered the “forge of peoples”. This concept relied on historical data about regular waves of migration by the Sarmatians and Turkic-Mongolian tribes of Huns, Bulgars, Avars, Khazars, Pechenegs, Cumans, Tatars, Kalmyks and others from Central Asian steppes to Europe over the last two millennia. The Russian and English colonization of Central Asia that began at that point further fuelled European interest in Central Asia.

However, the rapid development of linguistic palaeontology in the mid-19th century revealed that the Asian environment and climate did not match those described in the protolanguage. Reconstructed by the researchers, the common Indo-European protolanguage seemed to originate from a region with a temperate climate, flora rich in birch, aspen, pine and beech trees, and fauna teeming with grouses, beavers and bears. It also revealed that most Indo-European languages were localized in Europe, not Asia: a majority of old Indo-European river and lake names come from between the Rhine and the Dnieper.

READ ALSO: Linguistic Insights into Ukrainian History

From the late 19th century, Europe was widely considered the home of the Indo-European peoples. When German patriotism surged following the country’s unification, it could not but affect Indo-European studies since most researchers were ethnic Germans. This facilitated the concept that Indo-Europeans had come from Germany, especially given linguistic references to the temperate climate of the proto-homeland. The northern-European appearance of the oldest Indo-Europeans was another aspect in favour of this idea. Both Aryans in their Rigveda and ancient Greeks in mythology treated fair hair and blue eyes as symbols of aristocracy. Eventually, researchers concluded that the German language was a direct descendent of the proto-Indo-European language while other Indo-European languages emerged as Indo-Germans from the north of Central Europe migrated and mixed with aboriginals.

German linguist Gustaf Kossinna analysed archaeological findings and published Origin and Spread of the Teutons in Prehistory and Early History in 1926. The Nazis used it as a scientific argument for their aggression in Eastern Europe. Kossinna referred to Indo-Europeans as Indo-Germans and traced “14 colonial raids of megalithic Indo-Germans eastward through Middle Europe to the Black Sea” based on archaeological findings from the Neolithic Era and Bronze Age. Eventually, this politically motivated scenario of Indo-European settlement collapsed along with the Third Reich.

The steppe theory

The South Rus or steppe theory of the Indo-Europeans’ origin emerged alongside the Central European one, founded by German researcher Oswald Schrader. He summarized the findings of linguists and archaeological materials from kurgans (funeral mounds) on the southern Ukrainian steppe between 1880 and 1920, and stated that proto-Indo-Europeans were pastoralists that inhabited the Eastern European steppes in the 3rd-2nd millennia B.C. Since Indo-European languages are spread throughout Europe and Western Asia, Schrader believed that the common proto-Indo-European homeland had to be somewhere in the middle, i.e. the steppes of Eastern Europe. Other researchers from Great Britain, Poland, Lithuania, Russia and Ukraine also concluded that Indo-Europeans originated from the Ukrainian steppes. The Yamna or Pit Grave culture of the Pontic steppe shaped the assumptions of the 20th-century Indo-Europeanists. They interpreted it as the birthplace of the Indo-European protolanguage.

In this steppe version, the earliest Indo-Europeans emerged in Southern Ukraine in the 4th-3rd millennia B.C. after pastoralism split into a separate branch of the early economy. The process accelerated as the climate grew more arid and the steppes expanded, resulting in a crisis for the agriculture-based economies of the Balkans and the Danube area and creating favourable conditions for cattle breeding.

READ ALSO: The Land of Oium

The separation began in Southern Ukraine, on the frontier between the fertile right bank of the Dnieper inhabited by Trypillian farmers and the Eurasian steppes, which from then on became home to agile and warlike pastoral peoples. In the 4th millennium B.C., the territory of Ukraine became a buffer zone between the settled and peaceful farmers of Europe and the aggressive nomads of the Eurasian steppe. This defined Ukraine’s turbulent history for the next 5,000 years, up to the 18th century.

Cattle breeding skills inherited from the Trypillians quickly evolved into a separate industry in the steppes and forest-steppes of left-bank (eastern) Ukraine. Herds of cows and flocks of sheep were constantly relocating in search of pastures, making the pastoralists very flexible. In turn, this facilitated the spread of wheel transportation and the domestication of horses, which were initially used to pull wagons alongside oxen. This constant search for pastures led to violent conflicts among neighbouring groups and the militarization of these communities. Unlike the farmers who had matriarchal societies, the pastoralists’ leaders were male, since shepherds and warriors provided for life. The opportunity to own many cattle triggered stratification. In the militarized society, warlords emerged. Early fortresses were built, and cults of warriors and shepherds as supreme gods spread, along with common symbols such as chariots, weapons, horses, the sun cross (later appropriated by the Nazis) and fire.

The steppe economy of the 4th-3rd millennia B.C. was based on seasonal livestock grazing. The families settled in river valleys and grew barley and wheat, bred pigs, hunted and fished, while men spent more and more time with the herds of cows, sheep and horses at summer pastures. In spring, shepherds and armed warriors would take the cattle far into the steppes and return home in the fall. As pastoralism developed, this lifestyle grew more nomadic.

Early semi-nomadic pastoralists from the Ukrainian steppes left few settlements but numerous tombs behind. They belong to the Seredniy Stih (Sredny Stog), Yamna, Catacomb and Zrubna (Srubna or Timber-grave) cultures of the 4th-2nd millennia B.C. They are distinguished by their steppe graves with a kurgan over the grave and the body laid on the back with bent legs, covered with red ochre. Many graves had weapons (stone battle hammers and clubs) and rough clay pots decorated with rope imprints. Some had wheels in the corners to symbolize burial carts. Archaeologists are now finding stone anthropomorphic steles of family patriarchs with elements depicting chief warriors or shepherds.

From Rhine to Donets, India and Iran

Apparently, the homeland of proto-Indo-Europeans was not limited to the Ukrainian steppes and forest steppes since this does not explain why most Indo-European river and lake names are between the Rhine and Middle Dnieper in Central Europe. Some other elements of the Indo-European protolanguage, such as mountains and swamps, aspen, beech, yew, heather, grouse, beaver and the like do not fit into the steppe flora and fauna. These are more typical in parts of Europe that are cooler and damper than Southern Ukraine.

READ ALSO: The Predecessors of European Knights

Ukraine may have been an eastern wing of the Indo-European proto-homeland. The earliest Indo-Europeans probably emerged in the in the 4th millennium B.C. in the forest-steppe Dnieper valley on the eastern wing of the community that, given the territory with Indo-European hydronyms, covered the temperate part of Europe from the Dnieper to the Rhine.

The anthropological type of the earliest Indo-Europeans suggests that they come from the temperate zone of Europe. They were tall Northern Europeoids with strong bodies and fair hair, skin and eyes. These facts are proven by anthropological examinations of bones from the kurgans dating back to the 5th-3rd millennia B.C., as well as folklore and written sources.

Rigveda referred to the Aryans as Svitnya, meaning light or white-skinned. The heroes of The Mahabharata, a well-known Aryan epic, often had eyes like “blue lotuses”. In the Vedic tradition, a real Brahmin had to have brown hair and grey eyes. In the Iliad, the Achaeans – Achilles, Menelaus and Odyssey – had golden blond hair. Achaean women and even the goddess Hera and the god Apollo were fair-haired. Egyptian reliefs of the times of Thutmose IV (1420-1411 B.C.) portrayed Nordic-looking Hittite chariot riders and their Armenoid squires. In the mid-1st century B.C., the fair-haired descendants of the Aryans supposedly came to the Persian court from India. Ancient Chinese chronicles also mention blue-eyed blond men inhabiting Central Asian deserts.

READ ALSO: The Rise of the Celts

In search of pastures, nomadic pastoralists from the Pontic steppes travelled eastward to Asia and Altai, India and Iran, and westward to the Danube valley and the Balkans. At the lower Danube, migration split into three directions. One went southeast to Anatolia. The other headed to the Balkans and Greece, and the third moved westward to Central Europe. Thus, the pastoralists that inhabited the Black Sea steppes in the 4th-2nd millennia B.C. became the distant ancestors of Indo- and Iran Aryans, and the Anatolian, Greek, Armenian and Phrygian branches of the Indo-European language family. As they reached the upper Danube, they shaped the Central European epicentre of the Indo-European ethnogenesis from which the ancestors of Celts, Italics, Illyrians, Germans, Balts and Slavs emerged.

Thus, the Ukrainian steppes played a pivotal role in the emergence of Indo-European peoples. Their pastoral economy, the spread of wheeled transportation, the use of horses and oxen as draft animals and horseback riding gradually turned them into aggressive nomads and launched the unprecedented spread of the earliest Indo-Europeans from Southern Ukraine in the vast steppes all the way from the Upper Danube in the west to Altai and India in the east.

BIO

Leonid Zalizniak is a historian, Director of Stone Age Archaeology at the Archaeology Institute, National Academy of Sciences; and representative of Ukraine on the Palaeolithic Commission at the International Association of Protohistorians. He has published several books, including Essays on the Ancient History of Ukraine («Нариси стародавньої історії України», 1994); The Swidrian Reindeer-Hunters of Eastern Europe (1995); From Sclaveni to the Ukrainian Nation («Від склавинів до української нації», 1997); The Earliest Past of Ukraine («Найдавніше минуле України», 1997); Protohistory of Ukraine in the 10-5th Millennia B.C. («Передісторія України Х–V тис. до н. е.», 1998); Final Paleolithic Age of North-Western Eastern Europe («Фінальний палеоліт північного заходу Східної Європи», 1999); The Early History of Ukraine («Первісна історія України», 1999); The Origin of Ukrainians: Between Science and Ideology («Походження українців: між наукою та ідеологією», 2008), and more.