Polish pensioners Krystyna Trzcińska, 68, and her husband Józef Trzcinski, 72, at their home in the village of Zaraszów

PIOTR MALECKI FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

WSJ

Europe Faces Pension Predicament

Mismatch of lifespans and birthrates means too few workers are paying into state pension plans

ZARASZÓW, Poland— Krystyna Trzcińska, 68 years old, has farmed a strip of land in this corner of eastern Poland for more than four decades. Retired now, she grows clover between neat rows of raspberry bushes to feed her rabbits. The rabbits she eats, the berries she sells.

The berries bring in the equivalent of about $1,300 a year. To survive, she and her husband depend on pensions provided by Poland’s government.

State-funded pensions are at the heart of Europe’s social-welfare model, insulating people from extreme poverty in old age. Most European countries have set aside almost nothing to pay these benefits, simply funding them each year out of tax revenue. Now, European countries face a demographic tsunami, in the form of a growing mismatch between low birthrates and high longevity, for which few are prepared.

Europe’s population of pensioners, already the largest in the world, continues to grow. Looking at Europeans 65 or older who aren’t working, there are 42 for every 100 workers, and this will rise to 65 per 100 by 2060, the European Union’s data agency says. By comparison, the U.S. has 24 nonworking people 65 or over per 100 workers, says the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which doesn’t have a projection for 2060.

While the problem has long been building, it is gaining urgency as European countries’ debt troubles, growing out of the 2008 crisis, push governments to reassess their priorities. Greece, the worst off, has had to reduce the generosity of its pension system repeatedly. Though its situation is unusually dire, Greece isn’t the only European government being forced to acknowledge it has made pension promises it can ill afford.

“Western European governments are close to bankruptcy because of the pension time bomb,” said Roy Stockell, head of asset management at Ernst & Young. “We have so many baby boomers moving into retirement [with] the expectation that the government will provide.”

Even the U.S., with a Social Security trust fund of $2.8 trillion, faces criticism for promising more than it can afford. That is because the fund—which is mostly in the form of IOUs from the Treasury—is projected to fall short of the sums needed to cover all benefits in a dozen years or so, and run out in 2035. Europe’s situation is much worse.

The demographic squeeze could be eased by the influx of more than a million migrants in the past year. If many of them eventually join the working population, the result could be increased tax revenue to keep the pension model afloat. Before migrants are even given the right to work, however, they require housing, food, education and medical treatment. Their arrival will have effects on public finances that officials have only started to assess.

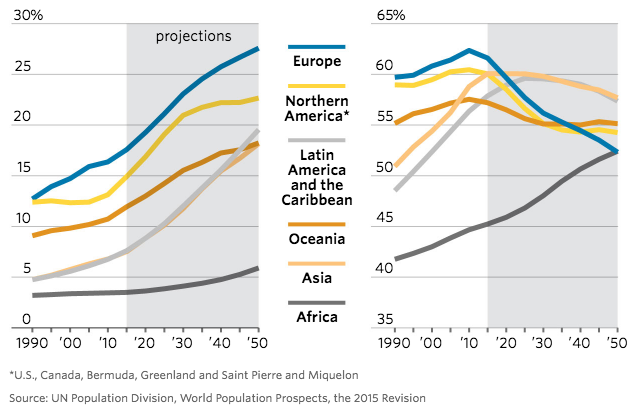

A Growing Mismatch

The share of Europe’s population 65 years and older is and will be larger than in any other region (first chart) and the share of Europe’s population 20–64 years old is shrinking. (second chart)

The pension squeeze doesn’t follow the familiar battle lines of the eurozone crisis, which pits Europe’s more prosperous north against a higher-spending, deeply indebted south. Some of the governments facing the toughest demographic challenges, such as Austria and Slovenia, have been among those most critical of Greece.

Germans, meanwhile, “are promoting fiscal rules in Spain and other countries, but we are softening the pension rules” at home, said Christoph Müller, a German academic who advises the EU on pension statistics. He pointed to a recent change allowing some workers to collect benefits two years early, at 63. A German labor ministry spokesman called that “a very limited measure.”

Europe’s state pension plans are rife with special provisions. In Germany, employees of the government make no pension contributions. In the U.K., pensioners get an extra winter payment for heating. In France, manual laborers or those who work night shifts, such as bakers, can start their benefits early without penalty.

While a few countries—including Norway, the U.K. and the Netherlands—have considerable savings in public funds or employer-sponsored pension plans, many others have little. Governments’ annual costs for public pensions equal a tenth of gross domestic product, according to the EU data agency Eurostat. That GDP percentage should be stable in coming decades, Eurostat estimates, though its forecast depends on numerous economic assumptions.

Across Europe, the birthrate has fallen 40% since the 1960s to around 1.5 children per woman, according to the United Nations. In that time, life expectancies have risen to roughly 80 from 69.

In Poland, birthrates are even lower, and here the demographic disconnect is compounded by emigration. Taking advantage of the EU’s freedom of movement, many Polish youth of working age flock to the West, especially London, in search of higher pay. A paper published by the country’s central bank forecasts that by 2030, a quarter of Polish women and a fifth of Polish men will be 70 or older.

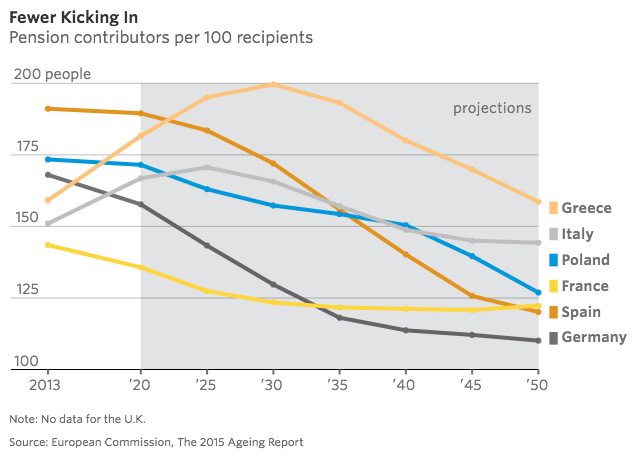

Fewer Kicking In

Pension contributors per 100 recipients

In 2012, the Polish government launched a series of changes in its main national pension plan to make it more affordable. One was a gradual rise in the age to receive benefits. It will reach 67 by 2040, marking an increase of 12 years for women and seven for men. The changes mean the main pension plan now is financially sustainable, said Jacek Rostowski, a former finance minister and architect of the overhaul.

The party that enacted the changes lost an election in October, however, and a central promise of the winning party is to undo them. Recently, Poland’s president introduced a bill to reverse some of the measures.

“You have to take care of people, of their dignity, not finances,” said Krzysztof Jurgiel, agriculture minister in the current Law & Justice Party government.

Ms. Trzcińska, the retired grower of berries and rabbits, doesn’t follow politics too closely. She switches channels when political debates such as the one over pensions appear on her TV screen. “They are all yelling at each other, I don’t understand it, and it’s unpleasant,” she said.

When she was young and living under communist rule, she recalls, her family worked the fields with horse-drawn plows and rarely left the village. She remembers winters so cold that a glass of hot tea placed on a window sill would freeze. For decades Ms. Trzcińska tilled a tiny farm of about 17 acres with her husband, Józef, retiring at 55, then the age when women could start collecting state pensions. They eventually gave most of their land to their son and two daughters.

For most of her working years, Ms. Trzcińska made no contributions to Poland’s special pension scheme for farmers. Modest though its payouts are—she receives the zloty equivalent of about $225 a month—barely a tenth of the plan’s benefits are covered by contributions from current farmers. Government budgets fill the gap.

Because her husband worked in a shop in addition to farming, he draws his benefit from the main national pension plan. After taxes, it equals about $200 a month. With their berry sales, the two have a combined posttax income equal to $6,400, about 60% of Poland’s median for two people.

“I’m not worried about myself,” Ms. Trzcińska said. “They already decided about my pension. But sometimes I see the debate and worry about what [my children’s] pensions will be.”

Her first daughter, 46-year-old Anna Mazurek, lives across the lane in Zaraszów. She teaches school—earning about $1,375 a month—cares for two children and spends many hours minding a shop she and her husband built. He too works at the shop, as well as growing wheat, barley and oats on their piece of the farm. “To live in the countryside, you have to have five jobs,” Ms. Mazurek said.

Once a year, the pension plan sends her an estimate of her benefits when she retires. The most recent was about $138 a month. A spokesman for the plan said it would provide at least $224 before taxes, a legal minimum the calculator doesn’t take into account.

An hour’s drive away in Lublin, a picturesque medieval town close to the Ukrainian border, her sister, Małgorazata Olechowska, works as an office manager for an EU-funded nonprofit for about $1,600 a month. She pays at least a third of her income in taxes, including 9.76% that is earmarked for retiree pensions. Her employer chips in an equal amount. The government pays all of that straight out to current pensioners, supplementing it with other tax revenue.

The system is “a mysterious machine,” Ms. Olechowska said. To her, it feels as if “there’s a huge black hole, and our money is going inside, and we get nothing from it.”

What both sisters do understand is that they will have to work long past the age at which their parents stopped, contribute more and likely retire with a less-generous pension.

It may be a more secure one, however, thanks to the 2012 overhaul that made the plan financially sounder. The changes mean that contributions from current workers and their employers now fund 84% of benefits provided by Poland’s national social security system, which includes not just pensions but also health-care and disability benefits.

Ms. Olechowska, 41, has considered investing in property to help fund her retirement but has taken no action. Her older sister, Ms. Mazurek, doubts she will be up to managing schoolchildren in her 60s but isn’t sure what to do about it. When the government raised the age for receiving a pension, she said: “I wasn’t angry, but I felt helpless.”

The EU has pressed European governments to be more upfront about their pension costs. They are required to publish forecasts of each year’s pension payouts. Only a few countries estimate the total debt burden of the pension promises they have made. In political discussion, most governments treat this as a kind of costless debt held off public balance sheets.

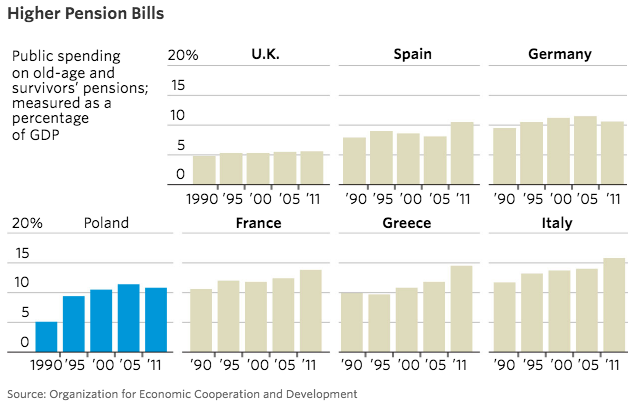

Higher Pension Bills

Starting in 2017, EU rules will require European governments to calculate the total amount they must pay current and future pensioners. Making this obligation more visible could spur them to deal with it, said Hans Hoogervorst, chairman of the International Accounting Standards Board and a former Dutch finance minister. “It will make clear that the current situation is unsustainable.”

That realization could trigger some tough decisions. Moritz Kramer, chief ratings officer for sovereigns at Standard & Poor’s, said European governments will have to admit at some point that current workers won’t receive as much from public pension plans.

Ernst & Young’s Mr. Stockell says he regularly asks a son in his 20s how much he is saving for his retirement. The answer is nothing. Mr. Stockell, who is 57, says even he hasn’t saved enough. “My expectation was that the company I worked for would provide,” he said.

—Martin Sobczyk and Andrea Thomas contributed to this article.

___

http://www.wsj.com/articles/europe-faces-pension-predicament-1457287588