Draghi Asset Buying Deepens the Hole in Europe’s Pension Funds

by Oliver Suess

BLOOMBERG

As he tries to jump start the economies of today, European Central Bank President Mario Draghi is punching holes in the retirements of tomorrow.

Draghi on Thursday said the ECB may continue asset buying beyond March 2017 until it sees inflation consistent with its targets. The purchases, along with low and negative interest rates from the ECB and the region’s national banks, are pushing more and more bond yields below zero, hurting European pension managers that are already struggling to fund retirement plans.

“Pension funds can’t meet their future obligations if interest rates remain as low as they currently are,” said Olaf Stotz, a professor of asset management at the Frankfurt School of Finance and Management. “Some sponsors will have no choice but to add more capital” to their pension plans.

Funds that supply retirement income of millions of European workers face a growing gap between the money they have and what they must pay out. To make up the shortfalls, they may have to tap their sponsoring companies or institutions, reduce or delay payouts or try to boost returns by investing in riskier assets. That mirrors the dilemma faced by pension managers from the U.S. to Japan who are also being affected by central bank monetary policy.

Money Shortage

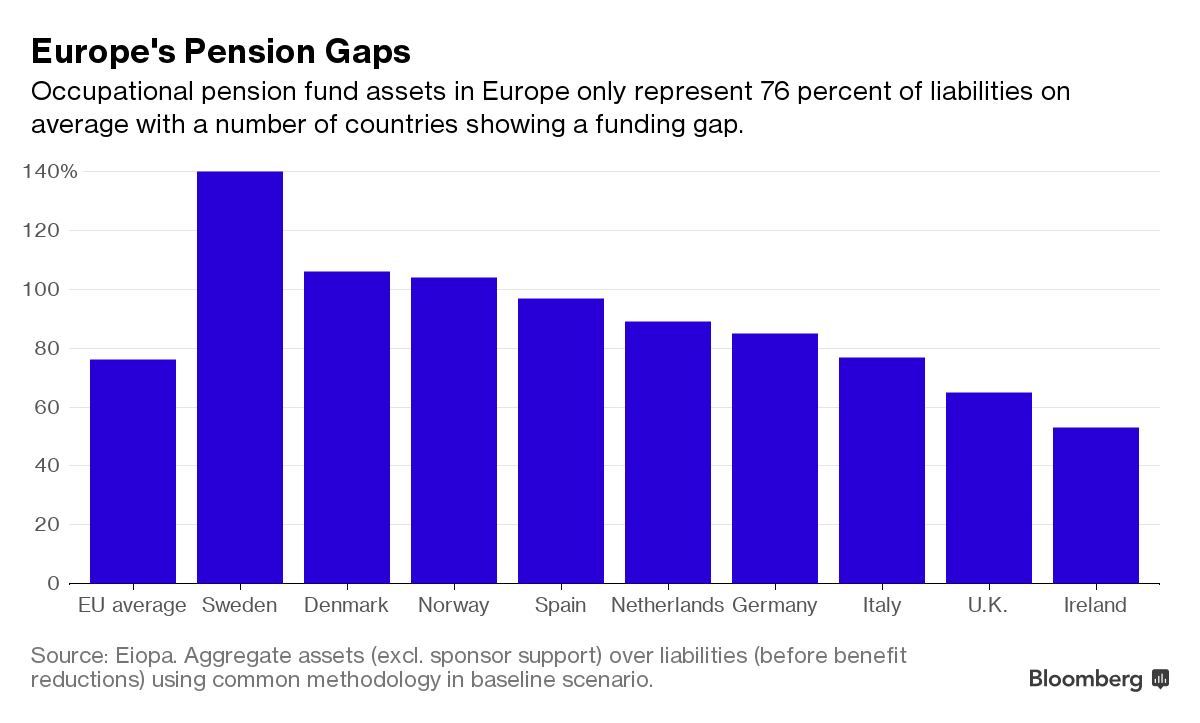

Low yields force funds to buy a greater variety of bonds or diversify their investments to generate a long-term income for their retirees. While some are profiting now by selling bonds purchased at lower prices in the past, they will struggle to get the same kind of returns from any new bonds they purchase. Occupational funds in Europe currently have resources to pay only about 76 percent of their commitments on average, according to the European insurance and pensions regulator Eiopa.

“Pension funds are more liberal in their investment decisions than insurers,” said Martin Eling, a professor of insurance economics at the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland. “Regulators will need to closely watch them as they are driven into higher-return assets such as corporate bonds and emerging markets investments.”

Risks Underestimated

EU regulations on the industry “might underestimate the risks,” Eiopa said by e-mail. It recommends measures including improved public disclosure so more beneficiaries know how their funds are investing. While pension systems and controls differ from country to country in Europe, regulators typically approve a pension plan’s design and set limits for certain investments. They also can intervene to make sure a fund can meet its obligations.Eiopa’s first stress test of the industry in Europe, published earlier this year, showed that occupational pension fund assets were 24 percent short of liabilities, a deficit of 428 billion euros ($484 billion) even before applying a shock scenario.

Central banks in Europe and Japan are relying on stimulus packages that include negative deposit rates to fuel inflation and revive the economy. That has pushed yields in countries such as Germany and Japan below zero, bringing the global pile of bonds with negative yields to about $8.9 trillion.

Pension liabilities for the 30 members of the benchmark DAX Index in Germany rose by about 65 billion euros this year to a record 426 billion euros as interest rates declined, according to consulting firm Mercer.

Investment Alternatives

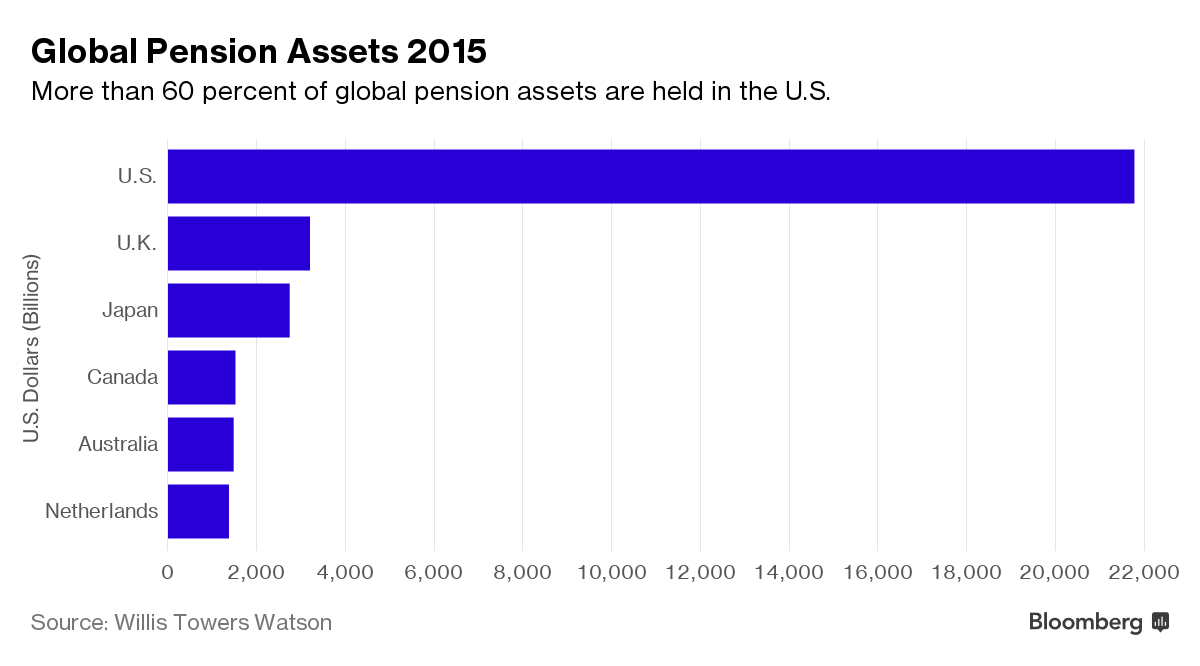

To help bolster returns, pension funds globally have boosted their investments in alternative assets to 24 percent from 5 percent in 1995, especially adding real estate and, to a lesser extent, hedge funds, private equity and commodities, according to consultant Willis Towers Watson Plc.

PFA in Copenhagen, Denmark’s biggest commercial pension fund, overseeing about $88 billion, plans to grow alternative assets to 40 billion kroner ($6 billion) from 10 billion kroner with a focus on renewable energy, infrastructure, private equity and direct lending, according to co-chief investment officer Christian Lage.

“It’s very tempting to crawl down the credit ladder and the liquidity ladder to hunt yield with QE artificially supporting markets, but you should always remember that the risk comes at a price,” Lage said.

PGGM, the investor for Europe’s second-largest pension fund, plans to increase its infrastructure assets by about 3 billion euros by the end of next year to boost returns. The Netherlands-based company is also making direct investments in areas including real estate, structured credit and private equity.

Defined Benefit

To tame future liabilities caused by low yields and aging populations, pension funds are moving away from the traditional defined benefit system, where payouts are fixed, to defined contribution plans where future pensions aren’t pre-determined. That moves the risk from the pension fund or company to the members or policy holders.

An aging Europe will have fewer workers to fund state pensions, which may mean higher taxes for employees. Last year, there were four workers for every person aged 65 or more in the European Union. By 2050, there’ll be just two, according to Eurostat estimates.

Stichting Pensioenfonds ABP, Europe’s biggest pension fund overseeing more than 370 billion euros, has told its members that it may need to cut pensions by 1 percent next year. The plan for Dutch public employees told its members that assets represented 90.6 percent of liabilities at the end of the first half. The company considers 90 percent a “critical level,” spokesman Jos van Dijk said.

Any payment reductions are likely to spark a backlash and in some countries it would be an illegal move.

“In Switzerland, the problem seems to be especially huge as pension funds need to pay a guaranteed conversion rate that’s defined by law,” said Eling of the St. Gallen University. “Several attempts to relieve that burden by increasing the retirement age or lowering the rate have failed so far.”

Political Resistance

Under Swiss law, any reduction of the minimum payments on mandatory occupational pensions must be approved in a public vote. If the current rate isn’t changed, Swiss pension funds will have a 73 billion-Swiss-franc ($75 billion) funding gap by 2030, according to Eling.

“In an aging society like the Swiss, older people are a large group; why should they vote to cut of their pensions?” Eling said. “Pension funds are in a slowly evolving crisis. Adjusting them today would be much easier and less costly than a radical rescue in ten years or so.”

The worst could still be ahead for pension funds in Europe according to Stotz of the Frankfurt School of Finance and Management.

“So far, pension funds have also been profiting from falling interest rates that kept bond prices rising,” he said. “As soon as the decline of interest rates ends or even reverts, pension funds will face their real test.”