CONSPIRACY ART: From JFK to 9/11 and Other Real Conspiracies that Shaped America

Everything Shall Be Revealed:

“Conspiracy Art” in Times of Disclosure and Apocalypse

“There is nothing hidden that will not be disclosed.”

(Luke 19:40)

Byron Belitsos

Political mistrust is so extreme and the pace of disclosure of deep state secrets is so slow that today’s America seems awash in conspiracies or rumors of conspiracy. That’s why we shouldn’t be surprised that these times of paranoia have given birth to a sub-genre of conceptual art that some curators are now calling “conspiracy art.” Apparently, the truth-telling process, now on hold in the mainstream media, has had to jump tracks to find another vehicle for its expression: independent artists. Especially since 9/11, art related to government conspiracy has become so preponderant that two large exhibits appeared in prestigious venues in New York City in the fall of 2018.

In this essay I review these two shows, “Everything Is Connected,” now on exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (through January 15), and “9/11: The Collapse of Conscience,” by Fredric Riskin, which was on display at Feldman Gallery in the SoHo through October. Today’s political gridlock has clearly opened up a space for artists willing to step through the looking glass to put their ideas in the service of a great unveiling of hidden truth. Sometimes their art even enacts the unveiling, but in a different dimension. Most of my review covers the show by Riskin, whose heroic effort offers renewed hope that “everything shall be revealed.”

Conspiracy Art, Emergent

I’ll start with the “Everything Is Connected” exhibit at the Met, which is significant for its wide sweep of highly original art by thirty artists that covers American conspiracy theories (so-called) going back to the JFK assassination—although the virtual absence of art that references 9/11 is a disturbing omission.

The first half of the show highlights artists such as Mark Lombardi, Jenny Holzer, and Hans Haacke who have engaged with public records in an effort to graphically portray criminal networks or political conspiracies that can be precisely documented. For me the most compelling installation of this sort at the Met show was a huge drawing by Mark Lombardi (1999), who has been called by the New York Times “the arch-conspiracist of contemporary American art.” The piece depict the Clintons’ alleged conspiratorial connections in Little Rock, Arkansas. Lombardi provides an elaborate flowchart that links up scores of financiers, drug smugglers, politicians, and criminals in a web of financial and political patronage that, we are told, the artist spent years researching. This and the other pieces in this section are graphical representations of publically available facts that might comprise the narrative of a lengthy expose in a book or a long piece in Vanity Fair.

In another genre entirely, I can’t help but give a very honorable mention in this connection to the 2017 Tom Cruise movie, “American Made,” that shocked many by alluding to Governor Clinton’s complicity in the CIA’s drug-running covert op headquartered in Mena, Arkansas during the Reagan era. (Cruise plays the role of CIA pilot Barry Seal.)

Some state crimes of this sort are becoming much better known, but what if a significant covert or criminal action is suspected, but the cover-up is elaborate and the accessible public documentation is scarce? Then we move to a more surreal realm of speculation that begins to fit the hackneyed stereotype of conspiracy theory. The Met show moves much more quickly toward this world than it needed to, in my estimation, but the pieces they curated are nonetheless compelling and often fascinating, though a few border on the absurd or caustic.

A section devoted to art related to the Black Panthers featured a rare video loop of a Panther named Fred Hampton, an articulate young black man widely thought to be the most brilliant leader emerging in the movement in the late 1960s. Hampton rants rather lucidly about police conspiracies and many other topics concerning repression of the black power movement (which in the case of the Panthers mainly consisted of humanitarian activities directed at supporting poor urban blacks). A short time later Hampton died in what was then described to be a Panther shoot-out with the police. But a criminal trial held much later proved that his death was a deliberate, pre-mediated police raid intended to kill him. All the bullet holes pointed inward toward Hampton’s bedroom; he had been shot while sleeping in his bed. Hampton’s conspiracy paranoia was justified.

I especially liked Rachel Harrison’s installation “Snake in the Grass” (1997). This consisted of photographs that the artist took at Dallas’s infamous grassy knoll. These images hang on drywall fragments suspended from the ceiling on wires in a large room; sound effects broadcast in the room are actual tapes of radio or TV reports from that day. The installation eerily raises questions still not answered about whether there was a second shooter on the far side of the knoll behind a wall, as numerous eye-witnesses have alleged.

There is just one allusion to 9/11 in a set of paintings by Sue Williams. One of her color-saturated works actually depicts the destruction of the World Trade Center; this canvas includes the word “nanothermite,” a military-grade explosive that has been proven in peer-reviewed scientific journals to have been found in the dust was shed from the collapse of the towers. Truly this is art in the services of disclosure.

Riskin’s Breakthrough Exhibit at the Feldman

A more ambitious effort by a single major artist, this time limited mainly to the 9/11 theme, was Feldman Gallery’s exbihit by Fredric Riskin that ran from September 11 to October 23.

Riskin is a Los Angeles-based conceptual artist and fine arts painter. Riskin’s first conceptual art exhibit at the Feldman, mounted in 1987, was extensively reviewed in art periodicals and the popular press, including New York Magazine, ARTnews, Artforum, The Village Voice, and Washington Times. National Public Radio did a lengthy interview with him.

Mounted thirty years later, Riskin’s newest show, “9/11: The Collapse of Conscience,” is based on 14 years of reflection, Fredric told me. This large immersive multimedia exhibit is a heroic attempt to get us to return with fresh eyes to the events of that day—including its somber aftermath of war, surveillance, secrecy, and torture.

Perhaps because the stakes are much higher and the truth-telling is much greater, Riskin’s work received only one published review—an inaccurate hit-piece by a young art critic named Zachary Small that appeared, of all places, in The Nation, entitled “Conspiracy Theories Are Not Entertainment: New York’s art world explores the paranoia haunting American politics.” Sorry to say, but Mr. Small comes across as small-minded, for in his haste to serve the public by warding us off from damaging “conspiracy theories” he entirely misses the point of Riskin’s work. Small goes so far as to accuse Riskin of being “Islamophobic,” when the obvious purpose of his show is to awaken our collapsed consciences, especially in regard to Muslim victims of torture. Small also laughably claims that the artist “baldly ignores the available evidence” about the collapse of the towers, but the evidence Small offers was itself entirely ruled out in the 9/11 Commission. Small, and his wantonly ill-informed editors at The Nation, are the ones doing us a public disservice. Small’s piece is demolished in an article by Ted Walter of ae911truth.org, entitled “Scolding the Art World for Showcasing ‘Conspiracy Theories,’ The Nation Doubles Down on Its Defense of the Official 9/11 Narrative.”

By publishing this hack piece, The Nation, once a prominent left-leaning magazine, shows how it has lost its critical edge. Small’s review continues the left’s long tradition of ridiculing those who question 9/11 orthodoxy—in this case even mocking a distinguished artist being exhibited at one of New York’s premier galleries. Then again, maybe Small’s piece is a step forward in a journalistic desert bereft of critical thinking, seeing that the rest of the left simply ignores voices like Riskin’s or David Ray Griffin.

Gallery owner Ronald Feldman shared with me that, after he had decided to mount the show at some point, a vivid dream led him to open on September 11. A man like Feldman has deep sensitivities about who he exhibits and when, as his experience in the art world is vast. Once Andy Warhol’s art manager, Feldman has by all accounts remained at the frontier of contemporary art. Feldman sees Riskin’s work as ahead of its time, pointing out to me how Riskin’s radical vision reminds him of similar instances in art history over the centuries. It will take a good while, Feldman explained, for Riskin’s intended audience among art collectors to catch up sufficiently for the gallery to sell prints from this collection, even in today’s white-hot art market.

According to the gallery, Riskin’s multimedia exhibit “reflects on the mystery, unseen political nuances, and dark pain of the 9/11 attack.” I would add that it especially heralds the fact that 9/11 and the chaos and violence that has followed it remain an unhealed wound in the American psyche. Riskin points to the need for empathy and healing for the victims of our wars and torture, but the exhibit also rouses us to an activist stance through an intense encounter with jarring visual imagery and visceral truths that in too many cases are hiding in plain sight. Riskin wants us to get that we have been massively deceived about 9/11—and even about such events as the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing.

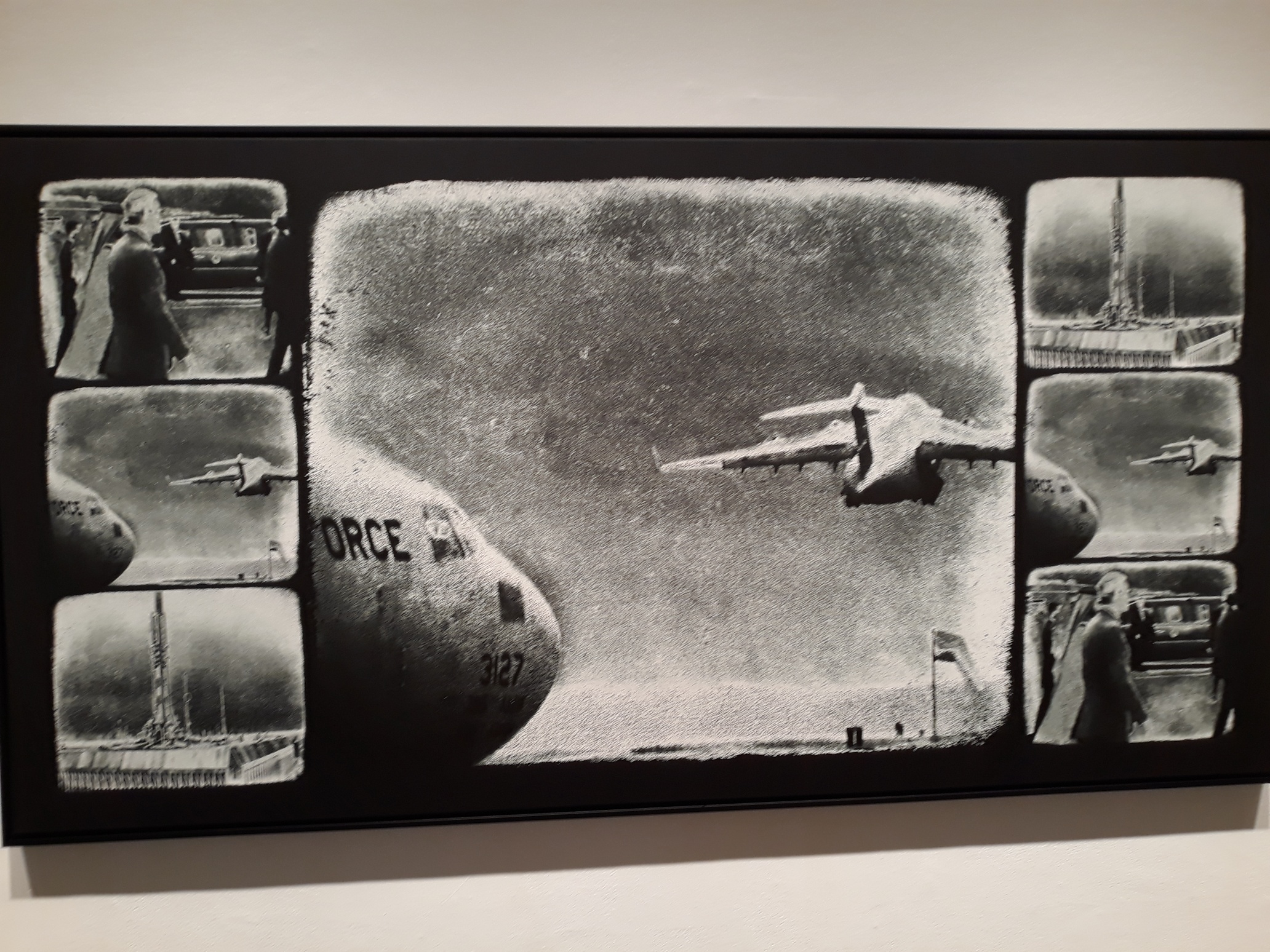

The entrance to the show is a contained space where you face at eye-level a row of five HDTV closed-circuit TV monitors playing a 20-minute video loop accompanied by a piped-in soundtrack. This footage plus the eerie audio track sets a harrowing tone for the entire exhibit. Riskin wants, I think, to induce a liminal state of consciousness, one marked by feelings of mystery but also of foreboding. His footage strings together short excerpts from actual events of 9/11 sliced into a montage of rare footage of political activities from that period. While some of the video materials are merely suggestive, other sequences are excerpted from hard news footage covering political figures such as Bush, Cheney, and Saudi princes. Riskin’s drone-like soundtrack blends a light background beat with unsettling bells tones and tingles, sounds of a Muslim call-to-prayer, even a hint of collapsing buildings. Our immersion in this entryway space has the effect of defamiliarizing us with respect to any preconceived ideas we may have had about 9/11. For me it induced a sense of sadness and some disorientation, but also an indignant feeling about the dark side of human nature on display.

As you enter the main body of the show you encounter 43 wall-mounted panels of images (20” x 27”) paired with text boxes and other forms of text display, plus 5 large, striking prints on canvas (43” x 82”). Almost all of these 48 images have a grim, grainy, black-and-white look that feels like out-takes from surveillance photography you were never meant to see. This is a multimedia installation, so the exhibit rooms are also pervaded by a second uncanny soundtrack created by Riskin. This audio loop, like the first one, is a dense, hypnotic, and eerily titillating soundscape.

Riskin’s prints and panels present strategically chosen images depicting disturbing aspects of 9/11 and its aftermath. Most are altered to varying degrees with a complex granularity as well as ghostlike or shadowy distortions that add a sense of secrecy and intrigue. To get these effects, the artist told me that he started by digitizing images (mainly journalistic or government photos), which he then reconstructed by rendering the pixels in innumerable photoshop layers, as many as 150 in some cases!

Representative panels of the show include: aerial shots of the twin towers after being hit by planes; shots of the collapse of Building 7; an ominous image of a drone aircraft; a shot of Dick Cheney hugging a Saudi prince overlaid with a fish-eye lens; a close-up of Bin Laden juxtaposed with an LA Times headline about his death; an image of a hijacker crossing security clearance at an airport; and a close-up of the military-grade explosive thermite found in the dust around the collapse towers. Most important, I think, are disturbing Abu Ghraib torture scenes that are carefully selected, cropped, and rendered, plus actual intelligence agency memos obtained by FOIA requests that concern torture. Others of Riskin’s images are harder to describe. Let’s say they are enigmatic symbols that are meant “to engage that which hovers at the borders of being invisible [so as to] to bring those elements into view,” as Riskin told Zackary Small.

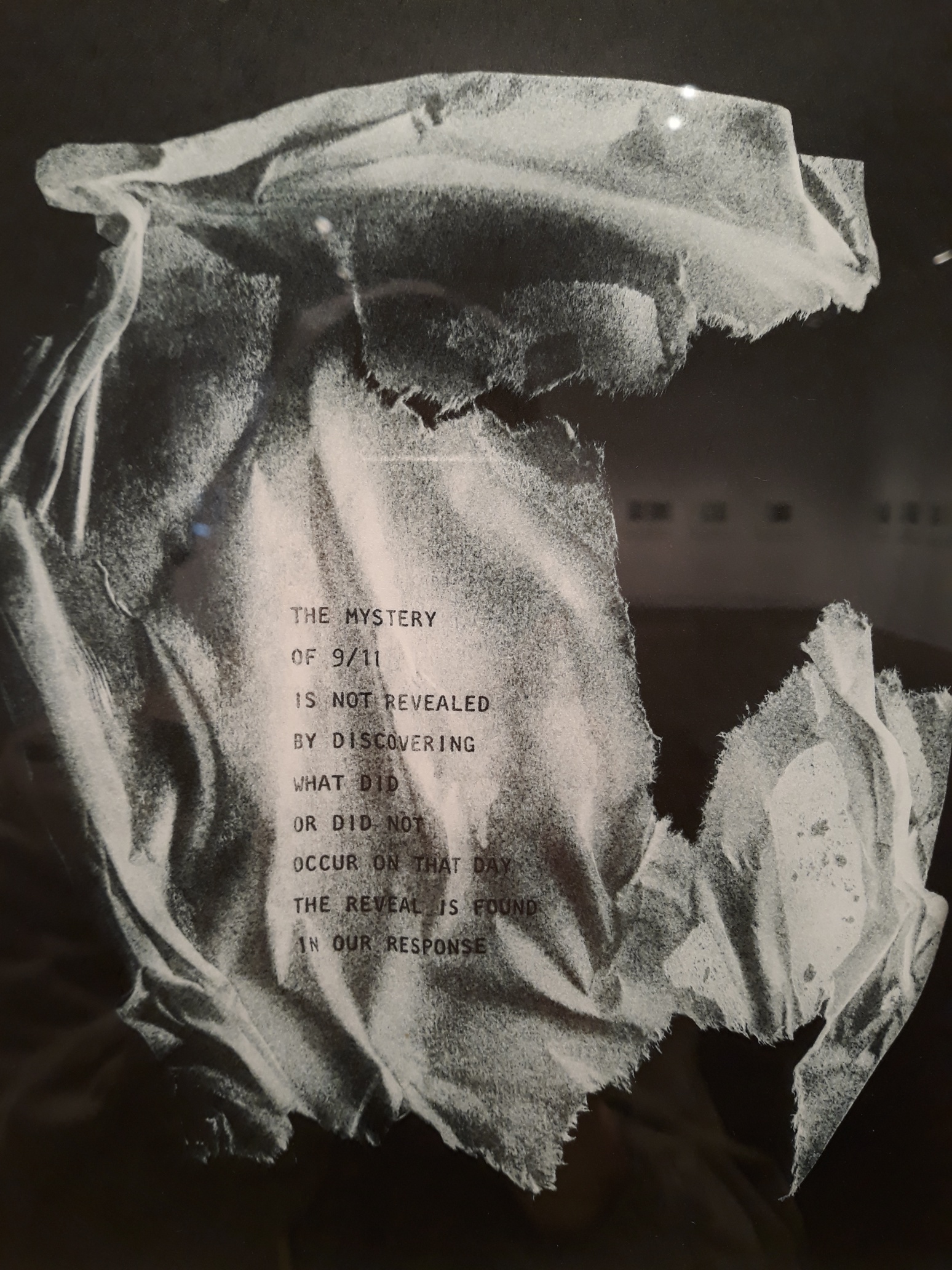

An equally essential aspect of this immersive show are the text boxes and text images that accompany most of the images, some rendered to look like they were retrieved from the waste basket of an intelligence operative. These are mainly written by the author, and some are only tangentially related to the image they accompany, thus giving a sense of the multi-dimensional nature of the phenomenon under observation. Many of Riskin’s epigrams evoke spiritual principles and moral exhortations in the face of the brutality and nihilism of 9/11’s perpetrators, who he clearly thinks are very close to home. Others of his texts contain notions drawn from quantum physics, esoteric religion, and energy psychology that seem to exalt these ideas if considered against the dark backdrop.

Aside from Riskin’s cryptic commentaries, I found very compelling a quote from the 1990 Geneva Convention Against Torture, and a few well-chosen scientific statements by experts, including from the inventor of the neutron bomb who states that the fertilizer bomb that destroyed the Oklahoma City Federal Building could not account for that explosion.

As you circulate through the show, the text materials serve to guide and elevate your internal dialogue, ultimately pointing you back to exhibit’s overarching message of the need for greater awareness, justice, compassion, and disclosure—or the lack thereof.

Upon my first viewing, I was so moved that I proposed a public event that would bring this work to the attention of a larger audience, especially my own colleagues in the 9/11 truth movement in the New York region. Riskin and Feldman consented to the idea, and so the gallery created a second opening of “9/11: The Collapse of Conscience,” which occurred on Saturday, October 17. I recruited several distinguished panelists to comment on the artist’s message and the gallery and I engaged in a massive outreach in the New York region with the assistance of 9/11 activists. Also present on the panel was the artist, Frederic Riskin and the gallery owner Ron Feldman, and I acted as the emcee. A crowd of about 80 showed up to our surprise.

The members of the panel were as follows:

Richard Squires, an actor, director, and distinguished writer. His work has been featured or reviewed in dozens of publications, including The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, Art Forum, the Village Voice, the Washington Post, and PBS. In addition to his play about 9/11, “A Handful of Dust,” four of his previous plays have been produced. He has written and directed three films.

Panelist Mark Crispin Miller, a distinguished professor of media studies at New York University. Miller is best known for his writing on American media and for his activism on behalf of democratic media reform. He is the author of the Loser Take All: Election Fraud and The Subversion of Democracy (2008) and Fooled Again, How the Right Stole the 2004 Elections (2005). His other books include Boxed In: The Culture of TV and Seeing Through Movies.

William Brinnier, a retired architect licensed to practice architecture in New York State since 1984. Bill lost his best friend, Frank DiMartini, on the 88th floor of the North Tower on 9/11. Frank was the construction manager of the World Trade Center. Bill shared his personal journey from uneasy acceptance of the official 9/11 narrative to questioning it, and to now challenging it.

To conclude, and to gain greater perspective in the face of a grim subject, let’s turn to a bit of theology and psychology—and entertain a glimmer of hope.

A Concluding Note on the Phenomenology of Light and Darkness

For the sake of sanity and balance, we should bear in mind that light ultimately is more powerful than darkness, despite appearances. Even Harvey Weinstein discovered that the light of truth, like physical light, is inescapable and insistent, as did Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman. According to its nature, the divine light—if you can admit that such a thing exists—seeks out and exposes falsehood, deception, and oppression, working through its many actors, especially its prophets and artists and courageous journalists. The divine spirit is, after all, ancestral to the human mind, if you can accept the theory according to which spirit is supervenient in relation to mind.

And this is why repressed truth has an inconvenient way of being unbearably difficult to force down below the surface, as Lady Macbeth discovered. Her need to “out” the stain of her “damned spot” illustrates the psychological truth that many criminal cover-ups will out themselves, at some point, consciously or through bizarre slips. Truth is dynamic and more buoyant than falsehood. If pushed down, it rises up with proportional force and goes an unstoppable journey back to the light of day, like a bubble down deep in a dark ocean that rises to the sunlit surface.

In Freud’s theory of dreams, the individual’s deep unconscious takes advantage of the weakened ego during sleep. It incessantly produces dream images representing thoughts that have been censored during waking life. The psyche seems to wrestle with suppressed material the way the biblical Jacob wrestled with angels, revealing its hidden plenty. Freud and his successors, especially Jung, have shown that untreated trauma, falsehood, and self-deception—seeking a way to release their charge—can distort the mind (and body) as a means of urgent self-expression, creating grotesque dreams and fantasies, even eventually derangement. Those with eyes to see can behold the disfigurement that sets in on the faces of perpetrators like Dick Cheney.

Criminologists know that human conscience acts like the hydraulic pressure that moves water through a pipe. Perpetrators of crimes instinctively feel the pressure of truth forcing its way up and out; that’s why many confess in the end and serve time, and it’s one reason why reluctant witnesses and whistleblowers with little to gain eventually do come forward.

In theological terms, all will be revealed when the time is propitious. Conspiracy art has become one crucial step in the uncovering of monstrous political deception, making the day closer when everything will be revealed. “For, there is nothing hidden that will not be disclosed, and nothing concealed that will not be known or brought out into the open.” (Luke 19:40)

Examples of Conspiracy Art :