The GOOGLE CONSPIRACY Laid Bare Unwittingly By An ‘Insider’

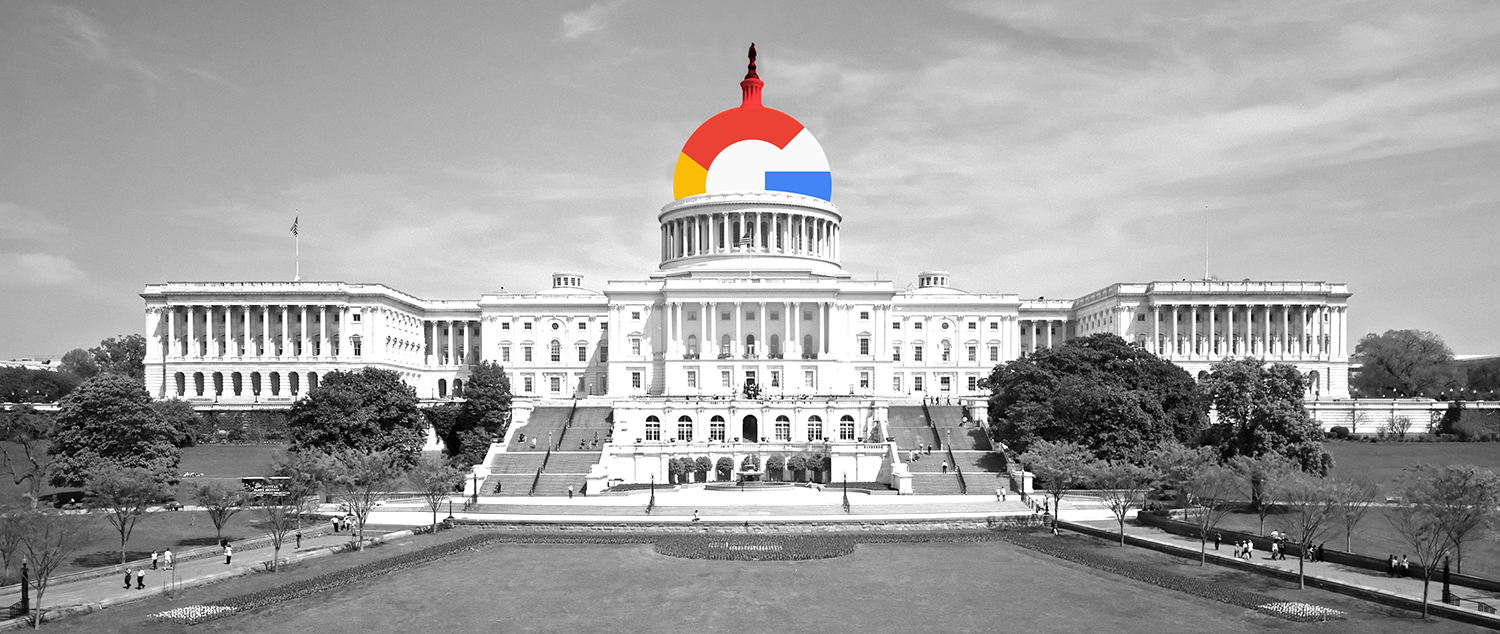

Google.gov

Amid growing calls to break up Google, are we missing a quiet alignment between “smart” government and the universal information engine?

The New Atlantis

Google exists to answer our small questions. But how will we answer larger questions about Google itself? Is it a monopoly? Does it exert too much power over our lives? Should the government regulate it as a public utility — or even break it up?

In recent months, public concerns about Google have become more pronounced. This February, the New York Times Magazine published “The Case Against Google,” a blistering account of how “the search giant is squelching competition before it begins.” The Wall Street Journal published a similar article in January on the “antitrust case” against Google, along with Facebook and Amazon, whose market shares it compared to Standard Oil and AT&T at their peaks. Here and elsewhere, a wide array of reporters and commentators have reflected on Google’s immense power — not only over its competitors, but over each of us and the information we access — and suggested that the traditional antitrust remedies of regulation or breakup may be necessary to rein Google in.

Dreams of war between Google and government, however, obscure a much different relationship that may emerge between them — particularly between Google and progressive government. For eight years, Google and the Obama administration forged a uniquely close relationship. Their special bond is best ascribed not to the revolving door, although hundreds of meetings were held between the two; nor to crony capitalism, although hundreds of people have switched jobs from Google to the Obama administration or vice versa; nor to lobbying prowess, although Google is one of the top corporate lobbyists.

Rather, the ultimate source of the special bond between Google and the Obama White House — and modern progressive government more broadly — has been their common ethos. Both view society’s challenges today as social-engineering problems, whose resolutions depend mainly on facts and objective reasoning. Both view information as being at once ruthlessly value-free and yet, when properly grasped, a powerful force for ideological and social reform. And so both aspire to reshape Americans’ informational context, ensuring that we make choices based only upon what they consider the right kinds of facts — while denying that there would be any values or politics embedded in the effort.

Follow The New AtlantisAddressing an M.I.T. sports-analytics conference in February, former President Obama said that Google, Facebook, and prominent Internet services are “not just an invisible platform, but they are shaping our culture in powerful ways.” Focusing specifically on recent outcries over “fake news,” he warned that if Google and other platforms enable every American to personalize his or her own news sources, it is “very difficult to figure out how democracy works over the long term.” But instead of treating these tech companies as public threats to be regulated or broken up, Obama offered a much more conciliatory resolution, calling for them to be treated as public goods:

Follow The New AtlantisAddressing an M.I.T. sports-analytics conference in February, former President Obama said that Google, Facebook, and prominent Internet services are “not just an invisible platform, but they are shaping our culture in powerful ways.” Focusing specifically on recent outcries over “fake news,” he warned that if Google and other platforms enable every American to personalize his or her own news sources, it is “very difficult to figure out how democracy works over the long term.” But instead of treating these tech companies as public threats to be regulated or broken up, Obama offered a much more conciliatory resolution, calling for them to be treated as public goods:

I do think that the large platforms — Google and Facebook being the most obvious, but Twitter and others as well that are part of that ecosystem — have to have a conversation about their business model that recognizes they are a public good as well as a commercial enterprise.

This approach, if Google were to accept it, could be immensely consequential. As we will see, during the Obama years, Google became aligned with progressive politics on a number of issues — net neutrality, intellectual property, payday loans, and others. If Google were to think of itself as a genuine public good in a manner calling upon it to give users not only the results they want but the results that Google thinks they need, the results that informed consumers and democratic citizens ought to have, then it will become an indispensable adjunct to progressive government. The future might not be U.S. v. Google but Google.gov.

“To Organize the World’s Information”

Before thinking about why Google might begin to embrace a role of actively shaping the informational landscape, we must treat seriously Google’s stated ethos to the contrary, which presents the company’s services as merely helping people find the information they’re looking for using objective tools and metrics. From the start, Google had the highest aspirations for its search engine: “A perfect search engine will process and understand all the information in the world,” co-founder Sergey Brin announced in a 1999 press release. “Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information, making it universally accessible and useful.”

Google’s beginning is a story of two idealistic programmers, Brin and Larry Page, trying to impose order on a chaotic young World Wide Web, not through an imposed hierarchy but lists of search results ranked algorithmically by their relevance. In 1995, five years after an English computer scientist created the first web site, Page arrived at Stanford, entering the computer science department’s graduate program and needing a dissertation topic. Focusing on the nascent Web, and inspired by modern academia’s obsession with scholars’ citations to other scholars’ papers, Page devised BackRub, a search engine that rated the relevance of a web page based on how often other pages link back to it.

Because a web page does not itself identify the sites that link back to it, BackRub required a database of the Web’s links. It also required an algorithm to rank the relevance of a given page on the basis of all the links to it — to quantify the intuition that “important pages tend to link to important pages,” as Page’s collaborator Brin put it. Page and Brin called their ranking algorithm PageRank. The name PageRank “was a sly vanity,” Steven Levy later observed in his 2011 book In the Plex — “many people assumed the name referred to web pages, not a surname.”

Page and Brin quickly realized that their project’s real value was in ranking not web pages but results for searches of those pages. They had developed a search engine that was far superior to AltaVista, Excite, Infoseek, and all the other now-forgotten rivals that preceded it, which could search for words on pages but did not have effective ways of determining the inherent importance of a page. Coupled with PageRank, BackRub — which would soon be renamed Google — was immensely useful at helping people find what they wanted. When combined with other signals of web page quality, PageRank generated “mind-blowing results,” writes Levy.

Wary of the fate of Nikola Tesla — who created world-changing innovations but failed to capitalize on them — Page and Brin incorporated Google in September 1998, and quickly attracted investors. Instead of adopting the once-ubiquitous “banner ad” model, Google created AdWords, which places relevant advertisements next to search results, and AdSense, which supplies ads to other web sites with precisely calibrated content. Google would find its fortune in these techniques — which were major innovations in their own right — with $1.4 billion in ad revenue in 2003, ballooning to $95 billion last year. Google — recently reorganized under a new parent company, Alphabet — has continued to develop or acquire a vast array of products focused on its original mission of organizing information, including Gmail, Google Books, Google Maps, Chrome, the Android operating system, YouTube, and Nest.

In Google We Trust

Page and Brin’s original bet on search has proved world-changing. At the outset, in 1999, Google was serving roughly a billion searches per year. Today, the figure runs to several billion per day. But even more stark than the absolute number of searches is Google’s market share: According to the JanuaryWall Street Journal article calling for antitrust action against Google, the company now conducts 89 percent of all Internet searches, a figure that rivals Standard Oil’s market share in the early 1900s and AT&T’s in the early 1980s.

But Google’s success ironically brought about challenges to its credibility, as companies eager to improve their ranking in search results went to great lengths to game the system. Because Google relied on “objective” metrics, to some extent they could be reverse-engineered by web developers keen to optimize their sites to increase their ranking. “The more Google revealed about its ranking algorithms, the easier it was to manipulate them,” writes Frank Pasquale in The Black Box Society (2015). “Thus began the endless cat-and-mouse game of ‘search engine optimization,’ and with it the rush to methodological secrecy that makes search the black box business that it is.”

While the original PageRank framework was explained in Google’s patent application, Google soon needed to protect the workings of its algorithms “with utmost confidentiality” to prevent deterioration of the quality of its search results, writes Steven Levy.

But Google’s approach had its cost. As the company gained a dominant market share in search … critics would be increasingly uncomfortable with the idea that they had to take Google’s word that it wasn’t manipulating its algorithm for business or competitive purposes. To defend itself, Google would characteristically invoke logic: any variance from the best possible results for its searchers would make the product less useful and drive people away, it argued. But it withheld the data that would prove that it was playing fair. Google was ultimately betting on maintaining the public trust. If you didn’t trust Google, how could you trust the world it presented in its results?

Google’s neutrality was critical to its success. But that neutrality had to be accepted on trust. And today — even as Google continues to reiterate its original mission “to organize the world’s information, making it universally accessible and useful” — that trust is steadily eroding.

Google has often stressed that its search results are superior precisely because they are based upon neutral algorithms, not human judgment. As Ken Auletta recounts in his 2009 book Googled, Brin and then-CEO Eric Schmidt “explained that Google was a digital Switzerland, a ‘neutral’ search engine that favored no content company and no advertisers.” Or, as Page and Brin wrote in the 2004 Founders Letter that accompanied their initial public offering,

Google users trust our systems to help them with important decisions: medical, financial, and many others. Our search results are the best we know how to produce. They are unbiased and objective, and we do not accept payment for them or for inclusion or more frequent updating.

But Google’s own standard of neutrality in presenting the world’s information is only part of the story, and there is reason not to take it at face value. The standard of neutrality is itself not value-neutral but a moral standard of its own, suggesting a deeper ethos and aspiration about information. Google has always understood its ultimate project not as one of rote descriptive recall but of informativeness in the fullest sense. Google, that is, has long aspired not merely to provide people the information they ask for but to guide them toward informed choices about what information they’re seeking.

Put more simply, Google aims to give people not just the information they do want but the information Google thinks they should want. As we will see, the potential political ramifications of this aspiration are broad and profound.

“Don’t Be Evil,” and Other Objective Aims

“Google is not a conventional company. We do not intend to become one.” So opened that novel Founders Letter accompanying Google’s 2004 IPO. It was hardly the beginning of Page and Brin’s efforts to brand theirs as a company apart.

In July 2001, after Eric Schmidt became chairman of the board and the month before he would become CEO, Page and Brin had gathered a small group of early employees to identify Google’s core values, so that they could be protected through the looming expansion and inevitable bureaucratization. As John Battelle describes it in his 2005 book The Search:

The meeting soon became cluttered with the kind of easy and safe corporate clichés that everyone can support, but that carry little impact: Treat Everyone with Respect, for example…. That’s when Paul Buchheit, another engineer in the group, blurted out what would become the most important three words in Google’s corporate history…. “All of these things can be covered by just saying, Don’t Be Evil.”

Those three words “became a cultural rallying call at Google, initially for how Googlers should treat each other, but quickly for how Google should behave in the world as well.” The motto exerted a genuine gravitational pull on the company’s deliberations, as Steven Levy recounts: “An idea would come up in a meeting with a whiff of anticompetitiveness to it, and someone would remark that it sounded … evil. End of idea.”

To Googlers, Levy notes, the motto “was a shortcut to remind everyone that Google was better than other companies.” This also seems to have been the upshot to Google’s rivals, to whom the motto smacked of arrogance. “Well, of course, you shouldn’t be evil,” Amazon founder Jeff Bezos told Battelle. “But then again, you shouldn’t have to brag about it either.”

Google’s founders themselves have been less than unified about the motto over the years. Page was at least equivocally positive in an interview with Battelle, arguing that “Don’t Be Evil” is “much better than Be Good or something.” But Brin (with Page alongside him) told attendees of the 2007 Global Philanthropy Forum that the better choice indeed would have been “Be Good,” precisely because “ultimately we’re in a position where we do have a lot of resources and unique opportunities. So you should ‘not be evil’ and also take advantage of the opportunity you have to do good.” Eric Schmidt, true to form as the most practical of Google’s governing troika, gives the slogan a pragmatic interpretation in his 2014 book How Google Works:

The famous Google mantra of “Don’t be evil” is not entirely what it seems. Yes, it genuinely expresses a company value and aspiration that is deeply felt by employees. But “Don’t be evil” is mainly another way to empower employees…. Googlers do regularly check their moral compass when making decisions.

As Schmidt implies, “Don’t Be Evil” has never exactly been self-explanatory — or objective. In a 2003 Wired profile titled “Google vs. Evil,” Schmidt elaborated on the motto’s gnomic moral code: “Evil,” he said, “is what Sergey [Brin] says is evil.” Even at that early stage in the company’s life, Brin recognized that the slogan was more portentous for Google itself than for other companies. Google, as gateway to the World Wide Web, was effectively establishing the infrastructure and governing framework of the Internet, granting the company unique power to benefit or harm the public interest. As the author of the Wired article explained, “Governments, religious bodies, businesses, and individuals are all bearing down on the company, forcing Brin to make decisions that have an effect on the entire Internet. ‘Things that would normally be side issues for another company carry the weight of responsibility for us,’ Brin says.”

“Don’t Be Evil” is a catchy slogan. But Google’s self-conception as definer and defender of the public interest is more revealing and weighty. The public focus on the slogan has distracted from the more fundamental values embodied in Google’s mission statement: “to organize the world’s information, making it universally accessible and useful.” On its face, Google’s mission — a clear, practical goal that everyone, it seems, can find laudable — sounds value-neutral, just as its organization of information purportedly is. But one has to ask: Useful for what? And according to whom?

What a Googler Wants

There has always been more to Google’s mission than merely helping people find the information they ask for. In the 2013 update of the Founders Letter, Page described the “search engine of my dreams,” which “provides information without you even having to ask, so no more digging around in your inbox to find the tracking number for a much-needed delivery; it’s already there on your screen.” Or, as Page and Brin describe in the 2005 Founders Letter,

Our search team also works very hard on relevancy — getting you exactly what you want, even when you aren’t sure what you need. For example, when Google believes you really want images, it returns them, even if you didn’t ask (try a query on sunsets).

Page acknowledged in the 2013 letter that “in many ways, we’re a million miles away” from that perfect search engine — “one that gets you just the right information at the exact moment you need it with almost no effort.” In the 2007 Founders Letter, they explain: “To do a perfect job, you would need to understand all the world’s information, and the precise meaning of every query.”

To say that the perfect search engine is one that minimizes the user’s effort is effectively to say that it minimizes the user’s active input. Google’s aim is to provide perfect results for what users “truly” want — even if the users themselves don’t yet realize what that is. Put another way, the ultimate aspiration is not to answer a user’s question but the question Google believes she should have asked. Schmidt himself drew this conclusion in 2010, as described in a Wall Street Journal article for which he was interviewed:

The day is coming when the Google search box — and the activity known as Googling — no longer will be at the center of our online lives. Then what? “We’re trying to figure out what the future of search is,” Mr. Schmidt acknowledges. “I mean that in a positive way. We’re still happy to be in search, believe me. But one idea is that more and more searches are done on your behalf without you needing to type.”

“I actually think most people don’t want Google to answer their questions,” he elaborates. “They want Google to tell them what they should be doing next.”

Let’s say you’re walking down the street. Because of the info Google has collected about you, “we know roughly who you are, roughly what you care about, roughly who your friends are.” Google also knows, to within a foot, where you are. Mr. Schmidt leaves it to a listener to imagine the possibilities: If you need milk and there’s a place nearby to get milk, Google will remind you to get milk. [Emphasis added.]

Or maybe, one is tempted to add: If Google knows you’ve been drinking too much milk lately, and thinks you’re the sort of person who cares about his health — and who doesn’t? — it will suggest you get water instead.

As Stanford’s Terry Winograd, Page and Brin’s former professor and a consultant on Gmail, explains to Ken Auletta, “The idea that somebody at Google could know better than the consumer what’s good for the consumer is not forbidden.” He describes his former students’ attitude as “a form of arrogance: ‘We know better.’” Although the comment was about controversies surrounding Gmail advertising and privacy — until June 2017, Gmail tailored its ads based on the content of users’ emails — the attitude Winograd describes also captures well Google’s aim to create the perfect search engine, which, in Schmidt’s words, will search “on your behalf.”

Fixing Search Results

Overshadowed by the heroic story of Google’s triumph through objective engineering is the story of the judgments of the engineers. Their many choices — reasonable but value-laden, even value-driven — are evident throughout the accounts of the company’s rise. And the history of Google’s ongoing efforts to change its search results to suit various needs — of foreign governments, of itself — indicates what Google might someday do to advance a particular notion of, in Barack Obama’s words, the “public good.”

As the story goes, Page and Brin designed Google to avoid human judgment in rating the relevance of web pages. Recounting Google’s original design, Steven Levy describes the founders’ opinion that “having a human being determine the ratings was out of the question,” not just because “it was inherently impractical,” but also because “humans were unreliable. Only algorithms — well drawn, efficiently executed, and based on sound data — could deliver unbiased results.”

But of course the algorithms had to be well drawn by someone, in accord with someone’s judgment. When the algorithms were originally created, Page and Brin themselves would judge the accuracy of search results and then tweak the code as needed to deliver better results. It was, Levy writes, “a pattern of rapid iterating and launching. If the pages for a given query were not quite in the proper order, they’d go back to the algorithm and see what had gone wrong,” then adjust the variables. As Levy shows, it was by their own account a subjective eyeball test: “You do the ranking initially,” Page explains, “and then you look at the list and say, ‘Are they in the right order?’ If they’re not, we adjust the ranking, and then you’re like, ‘Oh this looks really good.’”

Google continues to tweak its search algorithms. In their 2008 Founders Letter, Page and Brin wrote, “In the past year alone we have made 359 changes to our web search — nearly one per day.” These included “changes in ranking based on personalization” — Google had introduced its “personalized search” feature in 2004 to tailor search results to users’ interests. In newer versions, results are tailored to users’ search history, so that previously visited sites are more likely to be ranked higher. In 2015, Google’s general counsel told the Wall Street Journal, “We regularly change our search algorithms and make over 500 changes a year to help our users get the information they want.”

Sometimes Google adjusts its algorithms to make them “well drawn” to suit its own commercial interests. Harvard business professor Benjamin Edelman, an investigator of online consumer fraud and privacy violations, published findings in 2010 indicating that Google “hard-coded” its search algorithms, responding to queries for certain keywords by prioritizing its own web sites, such as Google Health and Google Finance. And in 2012 the Federal Trade Commission’s Bureau of Competition compiled a reportdetailing Google’s pattern of prioritizing some of its own commercial web pages over those of its competitors in search results.

Edelman’s and the FTC’s conclusions seem well founded, but even more striking are the 2007 words of Google’s own Marissa Mayer, then one of its senior executives. In a public talk, she was asked why searches for stock tickers had begun to list Google Finance’s page as the top result, instead of the Yahoo! Finance web site that had previously dominated. Mayer (who, ironically, would later leave Google to become CEO of Yahoo!) told the audience bluntly that Google did arrange to put Google Finance atop search listings, and that it was also company “policy” to do likewise for Google Maps and other sites. She quipped, “It seems only fair, right? We do all the work for the search page and all these other things, so we do put it first.”

Censorship and the Public Good

Some of the changes Google has made to its search results have been for apparently political reasons. In 2002, Benjamin Edelman and Jonathan Zittrain (also of Harvard) showed that Google had quietly deleted from the French and German search engines 113 pro-Nazi, anti-Semitic, white supremacist, or otherwise objectionable web sites — some of them “difficult to cleanly categorize.” Although the authors found “no mention of government-mandated (or -requested) removals,” it seemed clear that these were pages “with content that might be sensitive or illegal in the respective countries.”

Google also has accommodated governmental demands for much less laudable reasons. In 2006, Google attracted strong criticism for censoring its search results at Google.cn to suit the Chinese government’s restrictions on free speech and access to information. As the New York Times reported, for Google’s Chinese search engine, “the company had agreed to purge its search results of any Web sites disapproved of by the Chinese government, including Web sites promoting Falun Gong, a government-banned spiritual movement; sites promoting free speech in China; or any mention of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.”

Google’s entry into China under these conditions spurred significant debate within the company. Would bowing to an authoritarian regime’s demands to limit freedom empower the regime, harming Google’s mission? Or would continuing to make the search engine available — even under the restrictions imposed by the government — ultimately empower the Chinese people?

Andrew McLaughlin, then Google’s director of global public policy, urged his colleagues against partnering with the Chinese government because of how it would change Google. Steven Levy recounts McLaughlin’s reasoning: “My basic argument involved the day-to-day moral degradation, just dealing with bad people who are badly motivated and force you into a position of cooperation.” But Page was hopeful, and so, as Levy tells the story, “the Google executives came to a decision using a form of moral metrics” — that is, they tallied the evil of banning content against the good Google might bring to China. Schmidt later said, “We actually did an ‘evil scale’ and decided [that] not to serve at all was worse evil.”

After several difficult years in China, cold reality confirmed McLaughlin’s skepticism. In 2010, Google announced that it had discovered an “attack on our corporate infrastructure originating from China” and that a main target was the Gmail accounts of Chinese human rights activists. Google had had enough of its approach to China, announcing it would only continue operating its search engine in the country if it could come to an agreement with the government on how to do so without censorship. Without any formal declaration as such, the negotiations eventually failed. Google stopped censoring, but the Chinese government threatened action and gradually cracked down, with reports indicating that Google search has been blocked in mainland China since 2014, along with many other Google services.

Google’s awkward moral dance with China offers a case study in what happens when its two core missions — providing objective searches of all the world’s information and Not Being Evil — come into conflict. It suggests an important and paradoxical lesson: Google is willing to compromise the neutrality of its search results, and itself, for the sake of what it deems the broader public good, a goal that is plainly morally driven to begin with.

The question raised by the example of China, and in a limited but perhaps clearer way by France and Germany, is: What are the possibilities when Google is cooperating with a government with which it is less adversarial, and whose conception of the public good it more closely shares?

Google — Change Obama Could Believe In

Barack Obama first visited Google’s headquarters during a fundraising trip in California in 2004, around the time he burst onto the national stage with his riveting address to the Democratic National Convention. The visit made such an impression on Obama that he described it at length two years later in his book The Audacity of Hope. He recounts touring the Google campus and meeting Larry Page: “We spoke about Google’s mission — to organize all of the world’s information into a universally accessible, unfiltered, and usable form.” But Obama was particularly moved by “a three-dimensional image of the earth rotated on a large flat-panel monitor,” on which colored lights showed the ceaseless flurry of Google searches across the globe, from Cambridge to rural India. “Then I noticed the broad swaths of darkness as the globe spun on its axis — most of Africa, chunks of South Asia, even some portions of the United States, where the thick cords of light dissolved into a few discrete strands.”

Obama’s “reverie,” as he put it, was broken by the arrival of Sergey Brin, who brought him to see Google’s weekly casual get-together where employees could meet and discuss issues with him and Page. Afterward, Obama discussed with Google executive David Drummond the need for America to welcome immigrants and foreign visitors, lest other nations leapfrog us as the world’s leader in technological innovation. “I just hope somebody in Washington understands how competitive things have become,” Obama recalls Drummond telling him. “Our dominance isn’t inevitable.”

Obama returned to Google in November 2007, choosing it as the forum to announce his nascent presidential campaign’s “Innovation Agenda,” a broad portfolio of policies on net neutrality, patent reform, immigration, broadband Internet infrastructure, and governmental transparency, among other topics. His remarks reveal his deepening affinity for Google and its founders. Recounting the company’s beginnings in a college dorm room, he cast its vision as closely aligned with his own for America: “What we shared is a belief in changing the world from the bottom up, not the top down; that a bunch of ordinary people can do extraordinary things.” With words that would become familiar for describing Obama’s outlook, he said that “the Google story is more than just being about the bottom line. It’s about seeing what we can accomplish when we believe in things that are unseen, when we take the measure of our changing times and we take action to shape them.”

After Obama’s opening remarks, CEO Eric Schmidt — who would later endorse Obama and campaign for him — joined him on stage to lead a long and wide-ranging Q&A. While much of the discussion focused on predictable subjects, in the closing minutes Obama addressed a less obvious issue: the need to use technology and information to break through people’s ill-founded opinions. He said that as president he wouldn’t allow “special interests” to dominate public discourse, for instance in debates about health care reform, because his administration would reply with “data and facts.” He added, jokingly, that “if they start running ‘Harry and Louise’ ads, I’ll run my own ads, or I’ll send out something on YouTube. I’m president and I’ll be able to — I’ll let them know what the facts are.”

But then, joking aside, he focused squarely on the need for government to use technology to correct what he saw as a well-meaning but too often ignorant public:

You know, one of the things that you learn when you’re traveling and running for president is, the American people at their core are a decent people. There’s a generosity of spirit there, and there’s common sense there, but it’s not tapped. And mainly people — they’re just misinformed, or they are too busy, they’re trying to get their kids to school, they’re working, they just don’t have enough information, or they’re not professionals at sorting out all the information that’s out there, and so our political process gets skewed. But if you give them good information, their instincts are good and they will make good decisions. And the president has the bully pulpit to give them good information.

And that’s what we have to return to: a government where the American people trust the information they’re getting. And I’m really looking forward to doing that, because I am a big believer in reason and facts and evidence and science and feedback — everything that allows you to do what you do, that’s what we should be doing in our government. [Crowd applauds.]

I want people in technology, I want innovators and engineers and scientists like yourselves, I want you helping us make policy — based on facts! Based on reason!

The moment is captured perfectly in Steven Levy’s book In the Plex, where he writes of Obama: “He thought like a Googler.”

Obama then invoked the famous apocryphal line of Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan: “You are entitled to your own opinion, but you’re not entitled to your own facts.” Obama finished his speech by pointing to the crucial role that Google could play in a politics based on facts:

And part of the problem that we’re having … is, we constantly have a contest where facts don’t matter, and I want to restore that sense of decisions being based on facts to the White House. And I think that many of you can help me, so I want you to be involved.

Obama’s appeal to the Googlers proved effective. Not only did Eric Schmidt personally campaign for Obama in 2008, but Google tools proved instrumental to his 2012 reelection campaign machine, years before the Trump campaign used tech platforms to similar effect in 2016. According to a 2013Bloomberg report, Google’s data tools helped the Obama campaign cut their media budget costs by tens of millions of dollars through effective targeting. Schmidt helped make hiring and technology decisions for Obama’s analytics team, and after the election he hired the core team members as the staff of Civis Analytics, a new consulting firm for which Schmidt was the sole investor. The staff of Google Analytics, the company’s web traffic analytics product, cited the 2012 campaign’s use of their platform as a case study for its effectiveness at targeting and responding to voters. In words reminiscent of Obama’s odes to making policy based on reason and facts, the report claims that Google Analytics helped the reelection campaign support “a culture of analysis, testing and optimization.”

And Google’s relationship with Obama didn’t stop with the campaigns. In the years after his election, scores of Google alums would join the Obama administration. Among the most prominent were Megan Smith, a Google vice president, who became Obama’s Chief Technology Officer, and her deputy Andrew McLaughlin, who had been Google’s director of global public policy. Eric Schmidt joined the Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. In October 2014, the Washington Post recounted the migration of talent from Google to the Obama White House under the headline, “With appointment after appointment, Google’s ideas are taking hold in D.C.”

But the professional kinship between Google and the administration only saw comprehensive attention in its closing. In April 2016, The Intercept published “The Android Administration,” an impressive report laying out in great detail a case that “no other public company approaches this degree of intimacy with government.” It included charts that visualized the 252 job moves between Google and government from Obama’s campaign years to early 2016, and the 427 meetings between White House and Google employees from 2009 to 2015 — more than once a week on average. The actual number of meetings is likely even higher, since, according to reports of the New York Times and Politico, White House officials frequently conducted meetings outside the grounds in order to skirt disclosure requirements. As TheIntercept aptly observed, “the Obama administration — attempting to project a brand of innovative, post-partisan problem-solving of issues that have bedeviled government for decades — has welcomed and even come to depend upon its association with one of America’s largest tech companies.”

Obama — Change Google Could Believe In

The relationship seemed to bear real fruit, as the Obama White House produced a number of major policies that Google had advocated for. The most prominent of these was “net neutrality,” which proved to be one of the Obama administration’s top policy goals. The term refers to policies requiring broadband Internet providers to be “neutral” in transmitting information to customers, meaning that they are not allowed to prioritize certain kinds of traffic or to charge users accordingly. As I’ve previously described it in an online article for this journal, “net neutrality would prohibit networks from selling faster, more reliable service to preferred websites or applications while concomitantly degrading the service for disfavored sites and applications — such as peer-to-peer services for swapping bootleg music and video files.”

The Obama administration’s Federal Communications Commission (FCC) attempted twice to implement net-neutrality regulations, both times (in 2010 and early 2014) being rejected by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. Finally, in November 2014, President Obama exhorted his FCC to impose a strict regulatory framework typically used for “common carriers.” That is, the move sought to regulate broadband Internet companies with the same kind of framework long ago applied to railroads and traditional telephone companies. Providers are required to share their public networks and are prohibited from discriminating against any uses of it, as long as those uses are lawful. The FCC adopted Obama’s expansive approach in 2015 in a set of regulations that it called the “Open Internet Order.”

Google was originally ambivalent toward net neutrality, signing on to a policy proposal that might allow for some forms of traffic prioritization. But by 2014, Google came to fully endorse net neutrality. It joined other tech companies in a letter to the FCC warning that regulations allowing Internet providers to discriminate or offer paid prioritization would constitute a “grave threat to the Internet,” and it launched a public campaign on its “Take Action” website. The FCC returned to the issue in December 2017, with its new Trump-appointed chairman, Ajit Pai, leading the way toward repealing the Obama FCC’s rule. Google maintains a web page to rally support behind the Obama-era regulation, and the issue remains unresolved as of this writing.

Google enjoyed other policy successes with the Obama-era FCC. At least as early as 2007, Google had urged the FCC to exempt part of the radio spectrum from the longstanding, time-consuming process to obtain a non-marketable license for its usage. Instead, Google proposed treating it as an open market, in which the right to use portions of the spectrum could be easily bought and sold between companies. Google anticipated that the move could encourage competition among service providers, increasing consumer availability of mobile wireless access to the Internet — and to Google’s services. In 2014, as the Obama FCC began to propose a plan to reform its spectrum management, Google urged the FCC to dedicate the equivalent of four television channels for unlicensed uses. When the FCC adopted a plan that reallocated spectrum for such uses, Google posted a note on its public policy blog celebrating the FCC’s “important step toward powering tomorrow’s wireless broadband.”

In another example, in January 2016 the FCC proposed rules requiring cable TV providers to “unlock” their set-top boxes. Most consumers currently have to rent their set-top boxes from cable companies, so the move would allow competitors to offer devices at cheaper rates. It would also have permitted Google and other companies to access and repackage the cable channels as they saw fit. In theory, you could buy a single device through which you could watch Netflix, YouTube, HBO, and C-SPAN, all on your TV and without having to switch sources. The FCC proposal framed the move as aimed at “creating choice & innovation.” For Google, it would also have opened a new front in the nascent bid to compete directly against TV and Internet providers — already underway with Chromecast, its device for playing streaming Internet video on a TV, and Google Fiber, its ultra-fast Internet access service.

Two days after the FCC announced its proposal, Google hosted an event in its Washington, D.C. office near Capitol Hill to demonstrate its own prototype for a TV box, for a very specific audience: “It wasn’t an ordinary Google product event,” CNN reported. “There were no skydiving executives. No throngs of app developers. No tech press.” Instead, “The audience consisted of congressional staffers and federal regulators.” The proposal has since been canceled by President Trump’s FCC chairman.

The signs of a Google–government policy alignment during the Obama administration were not limited to the FCC. The landmark intellectual property reforms that Obama signed into law as the America Invents Act of 2011 found enthusiastic support from Google, which had joined with a number of other big tech companies to form the Coalition for Patent Fairness, which lobbied for the bill. Google’s main interest was in fighting so-called “patent trolls” — agents who obtain intellectual property rights not to create new products but to profit from infringement lawsuits. Companies like Google, which use and produce a vast array of individual technologies, are naturally vulnerable to such lawsuits. In comments submitted to the Patent and Trademark Office shortly after the bill’s enactment, Google (together with a few other tech companies) urged the PTO to adopt rules to reduce the costs and burdens of patent-related litigation. Their stated aim was to “advance Congress’ ultimate goal of increasing patent quality by focusing the time and resources of America’s patent community on productive innovation and strengthening the national economy.”

In February 2013, Obama returned to the subject of intellectual property during a “Fireside Hangout,” an online conversation with Americans arranged and moderated by Google, using its platform for video chat. Echoing Google’s position, Obama argued for still more legislation to further limit litigation by patent holders who “don’t actually produce anything themselves” and are “trying to essentially leverage and hijack somebody else’s idea and see if they can extort some money out of them.” The following year, Obama appointed Google’s former deputy general counsel and head of patents and patent strategy, Michelle K. Lee, to serve as director of the PTO.

Why did the Obama administration side so reliably with Google? Some might credit it simply to the blunt force of lobbying. In 2012, Google was the nation’s second-largest corporate spender on lobbying, behind General Electric; by 2017 it had taken the lead, spending $18 million. That money and effort surely had some effect, as did the hundreds of meetings between Google employees and the White House. Responding to a 2015 Wall Street Journal article on Google’s friendly relationship with the Obama administration, Google stated that their meetings covered a very broad range of subjects: “patent reform, STEM education, self-driving cars, mental health, advertising, Internet censorship, smart contact lenses, civic innovation, R&D, cloud computing, trade and investment, cyber security, energy efficiency and our workplace benefit policies.”

But there are some things even money can’t buy. Conjectures about the effectiveness of Google’s lobbying and its persistent visits miss that the Obama administration’s affinity for Google ultimately rested on more fundamental principles — principles held not by Obama alone, but by modern progressives generally.

“A Common Baseline”

Recounting Barack Obama’s 2007 visit to Google, Steven Levy observes that “Google was Obama Territory, and vice versa. With its focus on speed, scale, and above all data, Google had identified and exploited the key ingredients for thinking and thriving in the Internet era. Barack Obama seemed to have integrated those concepts in his own approach to problem solving.” Later Levy adds, “Google and Obama vibrated at the same frequency.”

It is not hard to see the similarities in Google’s and Obama’s social outlooks and self-conceptions. There is not a great distance between Google’s “Don’t Be Evil” and Obama’s “Don’t Do Stupid Sh**,” the glib slogan he reportedly started using in his second term to describe his foreign policy views. Nor does a vast gulf separate Google’s increasingly confident goal of answering questions you haven’t asked and Obama’s 2007 sketch of the American people as full of untapped common sense yet often ignorant, so that what they need is a president to give them the facts from the bully pulpit. The common theme is that we make wrong decisions not because the world is inherently complex but because most people are self-interested and dumb — except for the self-anointed enlighteners, that is.

For years, American progressives have offered paeans to “facts,” “evidence,” and “science,” and bemoaned that their opponents are at odds with the same. The 2008 platform of the Democratic Party, for example, vowed to “end the Bush Administration’s war on science, restore scientific integrity, and return to evidence-based decision-making.” As we’ve seen, Obama had already embraced that critique during his presidential campaign. “I’ll let them know what the facts are,” he told his Google audience in 2007, sure of his ability to discern the objective truths his ideological opponents missed or ignored or concealed. At the time, he saw Google as a partner in that endeavor.

But over a decade later, at the M.I.T. conference this February, Obama presented a less optimistic view of the major tech companies’ effect on national debates. (The event was off the record, but Reasonmagazine obtained and posted an audio recording.) He noted his belief that informational tools such as social media are a “hugely powerful potential force for good.” But, he added, they are merely tools, and so can also be used for evil. Tech companies such as Google “are shaping our culture in powerful ways. And the most powerful way in which that culture is being shaped right now is the balkanization of our public conversation.”

Rather than uniting the nation around a common understanding of the facts, Obama saw that Google and other companies were contributing to the nation’s fragmentation — a process that goes back to TV and talk radio but “has accelerated with the Internet”:

… essentially we now have entirely different realities that are being created, with not just different opinions but now different facts — different sources, different people who are considered authoritative. It’s — since we’re at M.I.T., to throw out a big word — it’s epistemological. It’s a baseline issue.

As in his 2007 talk at Google, Obama then offered the same (ironically apocryphal) anecdote about Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan winning a heated debate with the line, “You are entitled to your own opinion, but you’re not entitled to your own facts.” The radical difference in information presented between sources, such as Fox News and the New York Times editorial page, Obama explained, means that “they do not describe the same thing.” Google and social media, he seemed to imply, facilitate the creation of alternate realities, as poor information can be spread just as easily and can look just as authoritative as good information, and “it is very difficult to figure out how democracy works over the long term in those circumstances.”

Calling for “a common baseline of facts and information,” Obama urged that we need to have “a serious conversation about what are the business models, the algorithms, the mechanisms whereby we can create more of a common conversation.” Although he greatly admires Google and some of the other tech companies, he explained, we need some “basic rules,” just as we need them in a well-functioning economy. This shift must be oriented around an understanding that tech companies are “a public good as well as a commercial enterprise.”

Taken together, it was a significant change in tone from Obama’s 2007 talk at Google — as well as from his 2011 State of the Union Address, in which he called America a “nation of … Google and Facebook,” and meant it in the best possible way, as an example of American ingenuity. In 2018, after his presidency, he still saw America as a nation of Google and Facebook — but in a much more ominous way.

Meanwhile, and perhaps unbeknownst to Obama, Google already seems to be moving in the direction he indicated, self-imposing some basic rules to help ensure public debates are bound by a common baseline of facts.

“Evil Content”

Google’s founders have always maintained the conceit that Google’s ranking of information is fundamentally objective, determined by what is, or should be, most useful to users. But in recent years — particularly in the last two, as concern has grown from many quarters over the rise of “fake news” — Google has begun to tailor its search to prioritize content that it sees as more credible.

In April 2017, Google announced the worldwide release of its “Fact Check” feature for search results: “For the first time, when you conduct a search on Google that returns an authoritative result containing fact checks for one or more public claims, you will see that information clearly on the search results page.” A box will clearly display the claim and who stated it, together with who checked it and, ostensibly, whether it is true. The announcement explained that Google is not itself doing the fact-checking, and that instead it relies on “publishers that are algorithmically determined to be an authoritative source of information.” And while different publishers may sometimes come to different conclusions, “we think it’s still helpful for people to understand the degree of consensus around a particular claim and have clear information on which sources agree.” Google tied this new program directly to its fundamental mission: “Google was built to help people find useful information,” the release explained, and “high quality information” is what people want.

Only a few weeks later, Google announced that it would be taking much more direct steps toward the presentation of factual claims. In response to the problem of “fake news” — “the spread of blatantly misleading, low quality, offensive or downright false information” — Google has adjusted its search algorithms to down-rank “offensive or clearly misleading content, which is not what people are looking for,” and in turn to “surface more authoritative content.” In Google-speak, to “surface” is to raise items higher in search results.

Then, in November 2017, Google announced that it would further supplement its Fact Check approach with another labeling effort known as the “Trust Project.” Funded by Google, hosted by Santa Clara University, and developed in conjunction with more than 75 news organizations worldwide, the Trust Project includes eight “trust indicators,” such as “author expertise,” “citations and references,” and “diverse voices.” News publishers would be able to provide these indicators for their online content, so that Google could store and present this information to users in Google News and other products, much like how articles in Google News now display their publication name and date.

Two days later, Eric Schmidt — by then the Executive Chairman of Alphabet, Google’s new parent company — appeared at the Halifax International Security Forum and engaged in a wide-ranging Q&Aabout the geopolitical scene. Explaining the steps that Google and its sister companies, such as YouTube, were taking to combat Russian “troll farms,” terrorist propaganda, and other forms of fake news and abuse, Schmidt eventually turned to a broader point about Google’s role in vetting the factual — or moral — quality of search results.

We started with a position that — the American general view — that bad speech will be replaced by good speech in a crowded network. And the problem in the last year is that that may not be true in certain situations, especially when you have a well-funded opponent that’s trying to actively spread this information. So I think everybody is sort of grappling with where is that line.

Schmidt continued, offering a “typical example”: When “a judge or a leader, typically in a foreign country,” complains that illegal information appeared in Google search results, Google will respond that, within a minute and a half, they had noticed it themselves and taken it down. Using their crowdsourcing model, that time frame, Schmidt explains, is difficult to beat. But he goes on: “We’re working hard to use machine learning and AI to spot these things ahead of time … so that the publishing time of evil content is exactly zero.”

So what about Google’s role in the United States? Where would it find the line? At one point, an audience member, Columbia professor Alexis Wichowski, raised a question along the same lines that Obama would at M.I.T. a few months later — about the “lack of common narrative.” “We talk about echo chambers as if they’re some sort of inevitable consequence of technology, but really they’re a consequence of how good the algorithms are at filtering information out that we don’t want to see. So do you think that Google has any sort of role to play in countering the echo chamber phenomenon?” Schmidt responded that the problem was primarily one of social networks, not of Google’s search engine. But, he added, Google does have an important role to play:

I am strongly not in favor of censorship. I am very strongly in favor of ranking. It’s what we do. So you can imagine an answer to your question would be that you would de-rank — that is, lower-rank — information that was repetitive, exploitive, false, likely to have been weaponized, and so forth.

Were Schmidt referring only to the most manifestly false or harmful content, then his answer would have been notable but not surprising; after all, Google had long ago begun scrubbing racist and certain other offensive web pages from its search results in France and Germany. But the suggestion that Google might de-rank information that it deems false or exploitative more generally raises much different possibilities. Such an approach — employed, for example, in service of Obama’s call to bring Americans together around common facts relevant to policy — would have immense ramifications.

Payday

We see a glimpse and a possible portent of Google’s involvement in public policy in its fight against the payday loan industry. A type of small, high-interest loan usually borrowed as an advance on a consumer’s next paycheck, payday loans are typically used by low-income people who are unable to get conventional loans, and have been widely decried as predatory.

Google’s targeting of payday loans arguably began within their objective wheelhouse. In 2013, Google started tailoring its search algorithms to de-rank sites that use spamming tactics, such as bot queries, to artificially increase their rankings. Matt Cutts, then the head of Google’s web spam team, mentioned payday-loan and pornography sites as two chief targets. The editors of the news site Search Engine Land dubbed the new anti-spam code the “Payday Loan Algorithm.” (One editor attributes the name to Danny Sullivan, then also an editor of the site, who has since become Google’s public liaison of search.) At least as Google described it, these measures were simply aimed at countering exploitations of its ranking algorithm.

Yet even at this stage, there were indications that combating spam may not have been Google’s sole rationale. When someone tweeted at Cutts a criticism of the change — “Great job on payday loans in UK. Can’t find a provider now, but plenty of news stories. Way to answer users queries” — Cutts did not reply with a defense of combating spam tactics. Instead, he replied with a link to a news article about how the U.K. Office of Fair Trading was investigating payday lenders for anticompetitive practices and “evidence of financial loss and personal distress to many people.” “Seems like pretty important news to me?,” Cutts added. “OFT is investigating entire payday loan space?” Cutts’s reply was suggestive in two ways. One was a reminder that qualitative judgments about relevance have always been part of Google’s rationalizations for its search rankings. The other was the suggestion that top leadership at Google was well aware of the concerns that payday loans are predatory, and perhaps even saw it as desirable that information about the controversy be presented to users searching for payday lenders.

A clearer shift arrived in May 2016, when Google announced that it would start “banning ads for payday loans and some related products from our ads systems.” Although there was no mention of this change affecting search rankings, it was a more aggressive move than the de-ranking of spammers, as the rationale for it this time was explicitly political: “research has shown that these loans can result in unaffordable payment and high default rates for users.” The announcement quoted the endorsement of Wade Henderson, president and CEO of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights: “This new policy addresses many of the longstanding concerns shared by the entire civil rights community about predatory payday lending.” (It should be noted that it is not clear that Google’s move has been entirely effective. Five months after the announcement, a report in the Washington Examiner found that ads for intermediary “lead-generation companies that route potential borrowers to lenders” were still displaying.)

Unlike Google’s decision to combat spam associated with payday loans, there is no universal agreement about whether the loans themselves are exploitative or harmful. For example, a 2017 article in the Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance found that “payday loans may cause little harm while providing benefits, albeit small ones, to some consumers” and counseled “further study and caution.” An episode of the popular Freakonomics podcast gives reason to believe that the seemingly predatory practices of payday lenders owe in some significant measure to the nature of the service itself — providing quick, small amounts of credit to people vulnerable to sudden, minor financial shocks. It tells the story of a twenty-year-old Chicago man for whom a payday loan meant he could pay off a ticket for smoking, presumably avoiding even greater penalties for nonpayment. If this picture of payday loans is hardly rosy, it is not simple either. More to the point, there is no purely apolitical judgment of payday loans to be had. Google made the decision to ban payday-loan ads based not on a concern about legitimate search practices but on its judgment of sound public policy.

The timing of Google’s decision on this issue also came at a politically opportune moment, suggesting a fortuitous convergence in the outlooks of Google and the Obama administration. In March 2015, President Obama announced his administration’s opposition to payday loans, in a speech that coincided with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s announcement that it would formulate rules restricting such loans. The administration continued its campaign against payday loans through 2016, culminating with the CFPB’s formal release of proposed regulations in June. This was only a few weeks after Google announced its ban on payday-loan ads. And this May, Google, joined by Facebook, announced a similar ban on ads for bail-bond services — bail reform has recently become a popular cause among libertarians and progressives.

These kinds of political efforts may be a departure from Google’s founding principle of neutrality — but they are a clear extension of its principle of usefulness. Again, Google’s mission “to organize the world’s information, making it universally accessible and useful” is rife with value judgments about what information qualifies as useful.

It is not much of a further stretch to imagine that Google might decide that not only payday lenders themselves but certain information favorable to payday lenders is no longer useful to consumers either. If “research has shown” that payday loans are harmful or predatory, it is not difficult to imagine that contrary information — industry literature, research by people with ties to the industry, even simply articles that present favorable arguments — might fall under what Eric Schmidt deems “exploitive, false, likely to have been weaponized,” and be de-ranked.

And how much further, then, to other subjects? If it is widely believed that certain policy stances, especially bearing on science — say, on energy or climate policy or abortion — are simply dictated by available factual evidence, then arguments or evidence to the contrary could likewise be deemed a kind of exploitative informational fraud, hardly what any user really intends to find. Under the growing progressive view of political disagreement, it is not difficult to see the rationale for “de-ranking” many other troublesome sources.

“A Level Playing Field”

Another striking recent example — still unfolding as this article went to publication — illustrates the shaky ground on which Google now finds itself, the pressures to which it is vulnerable, and the new kinds of actions it might be willing to take in response.

On May 4, responding to ongoing concerns over how it and other tech companies were used by Russian agents to influence the 2016 U.S. elections, Google announced new policies to support “election integrity through greater advertising transparency,” including a requirement that people placing ads related to U.S. elections provide documentation of U.S. citizenship or lawful residency. This announcement came amid debate over Ireland’s referendum to repeal its constitutional limits on abortion. Just five days later, Google decided to “pause” all ads related to the referendum, including ads on YouTube.

As a rationale, Google cited only its recent election-integrity effort, and did not offer further explanation. Its decision came a day after a similar decision by Facebook to restrict referendum ads only to advertisers residing in Ireland, citing unspecified concerns that foreign actors had been attempting to influence the vote by buying Facebook ads. Multiple Irish Times articles cited Gavin Sheridan, an Irish entrepreneur who, starting ten days before Google’s decision, wrote a widely read series of tweets offering evidence that anti-repeal ads were being bought by pro-life groups in the United States.

Though Google’s and Facebook’s pause on ads applied to both sides of the campaign, it was not perceived by Irish activists as having equal impact. In fact, the response of both sides suggests a shared belief that the net effect of the restriction would favor the repeal campaign. A report in the Irish Timesquotes campaigners on both sides who saw it as a boon for repeal — a spokesperson for the repeal campaign praised the restriction as a move that “creates a level playing field,” while anti-repeal groups claimed it was motivated by concern that repeal would fail. As an article in The Irish Catholic described it, the pro-life activists argued that “mainstream media is dominated by voices who favour the legalisation of abortion in Ireland,” and “online media had provided them with the only platform available to them to speak to voters directly on a large scale.” (The referendum vote had not yet been held when this article went to publication.)

Google and Facebook alike have cited concerns over foreign influence on elections that sound reasonable, and are shared by many. But Irish Times reporter Pat Leahy, who said that Google declined to respond to questions about its rationale, also cited sources familiar with the companies’ thinking who said that they “became fearful in the past week that if the referendum was defeated, they would be the subject of an avalanche of blame and further scrutiny of their role in election campaigns.”

With this action, Google has placed itself in a perilous situation. A decision to prevent foreign actors from advertising in a country’s elections has clear merit, but it also requires unavoidably political reasoning. Moreover, although the action is on its face neutral, as it bars advertising from both sides of the campaign, the decision to apply the rationale to this particular case is also plainly subjective and political. Notice that, as justification for banning referendum ads in Ireland, Google cited only an earlier policy announcement that applied just to the United States. And whereas that policy had banned only foreign advertisers, in Ireland Google banned referendum ads from everyone, even Irish citizens and residents. Google did not offer rationales for either expansion, or explain whether the practices would apply to other countries going forward. From now on, Google’s decision to invoke one rationale in one case and another rationale in another will inevitably appear ad hoc and capricious.

Whatever its real motives, Google — which surely knew full well that its action would benefit the repeal campaign — has left itself incapable of credibly rebutting the charge that politics entered into its decision. And if political considerations are legitimate reasons for Google in these particular cases, then all other cases will become open to political pressure from activists too. Indeed, failure to act in other cases, invoking the old “digital Switzerland” standard of nonintervention, will now risk being seen as no less capricious and political.

From Antitrust to Woke Capital

All around, there is a growing unease at Google’s power and influence, and a rising belief from many quarters that the answer is antitrust action. It certainly seems like the sort of company that might require breaking up or regulating. As noted earlier, the Wall Street Journal recently found that Google’s market share of all Internet searches is 89 percent, while it scoops up 42 percent of all Internet advertising revenue.

Some might draw solace from the fact that users can switch to a different search engine anytime. “We do not trap our users,” Eric Schmidt told a Senate subcommittee in 2011. “If you do not like the answer that Google search provides you can switch to another engine with literally one click, and we have lots of evidence that people do this.” That Google search has competition is true enough, but only up to a point, because Google enjoys an immense and perhaps insurmountable advantage over aspiring rivals. Having accumulated nearly twenty years of data, its algorithms draw from a data set so comprehensive that no upstart search engine could ever begin to imitate it. Schmidt himself recognized this in 2003, when he told the New York Times that the sheer size of Google’s resources created an uncrossable moat: “Managing search at our scale is a very serious barrier to entry.” And that was just a few years into Google’s life; the barrier to entry has grown vastly wider since.

It is not hard to imagine the federal government bringing antitrust action against Google someday, as it did in 1974 against AT&T and in 2001 against Microsoft. Congress has taken an interest in Google’s practices: In 2011, the Senate’s antitrust subcommittee convened a hearing titled “The Power of Google: Serving Consumers or Threatening Competition?” And in 2012, staffers of the Federal Trade Commission completed a long and detailed report analyzing Google’s practices, half of which was later obtained and published by the Wall Street Journal.

The report found a variety of anticompetitive practices by Google, including illegally copying reviews from Amazon and other websites to its own shopping listings; threatening to remove these websites from Google’s search results when they asked Google not to copy their content; and disfavoring competitors in its search results. The report recommended an antitrust lawsuit against Google, citing monopolistic behavior that “will have lasting negative effects on consumer welfare.” But the commission rejected the recommendation of its staff, deciding unanimously to close the investigation without bringing legal action. Instead, it reached a settlement with Google in which the company agreed to change some of its practices. The European Union, however, has not been so hesitant, levying a $2.7 billion fine against Google in 2017 for similar practices.

But while progressive critics of Google seem to focus exclusively on either regulation or breakup as the natural remedies for its seeming monopoly, they forget the third possibility: that government might actually draw closer to business, collaborating toward a shared vision of the public interest. Collaboration between government and industry giants would not be a departure from progressivism; quite the contrary, there is some precedent in New Deal economic policy, as recounted by E. W. Hawley in The New Deal and the Problem of Monopoly (1966). FDR-era proponents of the “business commonwealth” approach believed that certain business leaders “had taken and would take a paternalistic and fair-minded interest in the welfare of their workers,” had moreover “played a major role in the creation of American society,” and that therefore they “were responsible for its continued well-being.” Accordingly, the argument went, “they should be given a free hand to organize the system in the most efficient, rational, and productive manner.” Government would retain a “supervisory role,” but this would not be an onerous task so long as an industry’s interests were generally seen to be “identical with those of society as a whole.”

While this approach, unsurprisingly, was first advanced by the business community, it became a core component of the first New Deal’s crown jewel, the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, which empowered industry groups to write their own “codes of fair competition” in the public interest, under the president’s oversight. The law was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court two years later. But until then its cooperative provisions embodied, in Hawley’s words, “the vision of a business commonwealth, of a rational, cartelized business order.” By coupling those provisions with the more familiar progressive policies of antitrust and regulation, the NIRA, “as written … could be used to move in any of these directions,” thus embodying progressivism’s ambivalence as to whether it is better to beat Big Business or join it.

One should not draw too close a connection between policy then and now. But Hawley’s description bears a striking resemblance to modern progressive visions of what Google is and perhaps ought to become. Although progressives have traditionally been deeply suspicious of corporate power in our government and in our society, and corporations in turn have traditionally shown little interest in convincing progressives otherwise, that trend may be changing, as New York Times columnist Ross Douthat suggested in February. Citing recent corporate advocacy on behalf of gun control, immigration, and gay and transgender rights, Douthat observed that “the country’s biggest companies are growing a conscience, prodded along by shifts in public opinion and Donald Trump’s depredations and their own idealistic young employees, and becoming a vanguard force for social change.” The usual profit motives have not been displaced, of course, but some major corporations seem increasingly interested in obligations of social conscience. It is, to quote the column’s headline, “the rise of woke capital.”

In important senses, Google has defined itself from the start as ahead of the woke curve. “We have always wanted Google to be a company that is deserving of great love,” said Larry Page in 2012. In establishing Google as a company defined by its values as much as its technology, Page and Sergey Brin have long made clear their desire to see Google become a force for good in the world. In 2012, Page reaffirmed that vision in an interview with Fortune magazine, describing his plan to “really scale our ambition such that we are able to cause more positive change in the world and more technological change. I have a deep feeling that we are not even close to where we should be.”

As Google’s sense of public obligation grows, and as progressive government becomes ever more keen on technology as a central instrument of its aims and more aware of tech companies’ power to shape public debates, it is not difficult to see how Google’s role could expand. At the very least, Google’s ability to structure the information presented to its users makes it a supremely potent “nudger.” As Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein argue in their 2008 book Nudge, how information is presented is a central aspect of “choice architecture.” As they put it,

public-spirited choice architects — those who run the daily newspaper, for example — know that it’s good to nudge people in directions that they might not have specifically chosen in advance. Structuring choice sometimes means helping people to learn, so they can later make better choices on their own.

If the “public-spirited” publisher of a daily newspaper can have such an effect on a community, just imagine the impact Google might have nationwide, even worldwide.

This, of course, would be a scenario well beyond merely nudging. As the de facto gateway to the Internet, Google’s power to surface or sink web sites is effectively a power to edit how the Internet appears to users — a power to edit the world’s information itself. This is why a decision by Google to “de-index” a web page, striking it from its search results altogether (usually for a serious violation of guidelines) is commonly called Google’s “death penalty.” In a sense, Google exercises significant power to regulate its users in lieu of government. As Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig argued in his seminal 1999 book Code:

While of course code is private, and of course different from the U.S. Code, its differences don’t mean there are not similarities as well. “East Coast Code” — law — regulates by enabling and limiting the options that individuals have, to the end of persuading them to behave in a certain way. “West Coast Code” does the same.

Whether we think of Google as acting in lieu of government or in league with government — either Lessig’s codemaker-as-lawmaker or Thaler and Sunstein’s public-spirited choice architect — Google is uniquely well suited to help further the aims of progressive government along the lines that President Obama described, creating a “common baseline of facts and information.” So will Google someday embrace that role?

4 issues ~ $24Subscribe to The New Atlantis.

4 issues ~ $24Subscribe to The New Atlantis.

Adjusting the Signals

There has long been a fundamental tension between the dual missions — being trusted as the source of objective search results and Not Being Evil — by which Google has sought to earn the public’s love.

That this tension is now coming to a head is evident in a pair of statements from Google over seven years apart. In November 2009, outrage arose when users discovered that one of the top image results when querying “Michelle Obama” was a racist picture. Google responded by including a notice along with the search results that linked to a statement, which read:

Search engines are a reflection of the content and information that is available on the Internet. A site’s ranking in Google’s search results relies heavily on computer algorithms using thousands of factors to calculate a page’s relevance to a given query.

The beliefs and preferences of those who work at Google, as well as the opinions of the general public, do not determine or impact our search results…. Google views the integrity of our search results as an extremely important priority. Accordingly, we do not remove a page from our search results simply because its content is unpopular or because we receive complaints concerning it.

Compare this statement to the company’s April 2017 announcement of its efforts to combat “fake news”:

Our algorithms help identify reliable sources from the hundreds of billions of pages in our index. However, it’s become very apparent that a small set of queries in our daily traffic … have been returning offensive or clearly misleading content, which is not what people are looking for…. We’ve adjusted our signals to help surface [rank higher] more authoritative pages and demote low-quality content, so that issues similar to the Holocaust denial results that we saw back in December are less likely to appear.

Google links to a December 2016 Fortune article that explains, “Querying the search engine for ‘did the Holocaust happen’ now returns an unexpected first result: A page from the website Stormfront titled ‘Top 10 reasons why the Holocaust didn’t happen.’”

The example is instructive. The problem here is that Google does not claim that — as with the spammy payday loan results — there were any artificial tactics that led to this search result. And Google’s logic — “offensive or clearly misleading content … is not what people are looking for” — is peculiar and telling. For search results are supposed to be objective in no small part because they’re based on massive amounts of data about what other people have actually looked for and clicked on. Google seems to have it backward: The vexing problem is that people are increasingly getting offensive, misleading search results because that’s increasingly what people are looking for.

Google is now faced squarely with the irresolvable conflict between its core missions: The information people objectively want may, by Google’s reckoning, be evil. Put another way, there is a growing logic for Google to transform its conception of what is objective to suit its conception of what is good.

The most recent update to Google’s Code of Conduct, released in April, may be telling. The previous version had opened with the words “Don’t be evil” — defined, among other things, as “providing our users unbiased access to information.” But the new version opens with an unspecified reference to “Google’s values,” adds a new mention of “respect for our users,” and now omits any assurance of providing unbiased information.