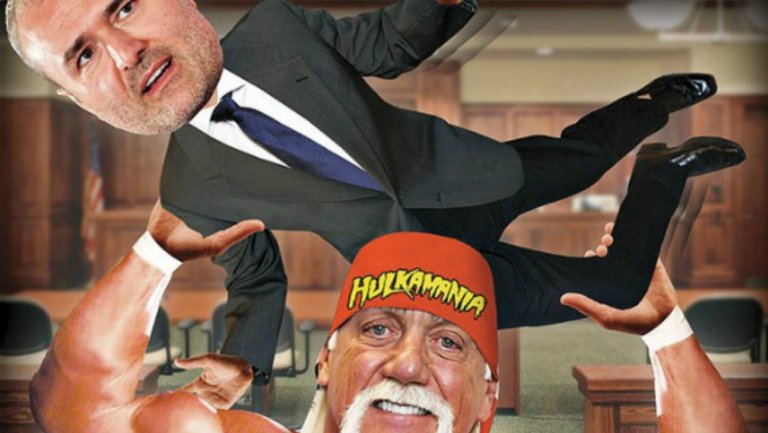

Media Companies Just Got More Bad News in Gawker Bankruptcy

Eriq Gardner

Hollywood Reporter

For many in the media, a billionaire secretly funding litigation that brought down Gawker.com was bad enough. Some legal observers, however, will point out that Hulk Hogan’s $140 million verdict in March 2016 over a sex tape didn’t create much legal precedent. On Monday, that might have changed with a new opinion from a New York bankruptcy judge that touches on a hot legal topic. It’s a decision that could have the effect of making it easier to sue media and entertainment companies.

First, some background.

The fallout of Gawker’s trial loss was Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Most of Gawker Media’s assets were then sold to Univision with the bankruptcy estate then coming to a settlement with Hogan and others. As the administrator for the Gawker estate looks to liquidate the rest of the assets — including the flagship site — Chuck Johnson has come forward to lodge an objection to the liquidation plan.

Johnson is the owner of GotNews and is described as a member of the alt-right community. He’s also been a fierce enemy of Gawker. On Dec. 9, 2014, Gawker published a story titled “What is Chuck Johnson, and Why? The Web’s Worst Journalist, Explained.”

He then sued Gawker.

Johnson now asserts that each of his claims against Gawker is worth $20 million. The liquidation plan establishes a mere $1.5 million reserve for his claims.

U.S. bankruptcy judge Stuart Bernstein was given two big issues to answer.

The first dealt with whether Johnson’s defamation and privacy claims amount to “personal injury torts.” Since bankruptcy courts only have jurisdiction to exercise power with respect to matters that are core to a bankruptcy estate — and since personal injury torts or wrongful death claims have been designated as not core — this is important. The question thus becomes whether Johnson’s claims are within the bankruptcy court’s jurisdiction.

Fortunately for the Gawker estate, Bernstein rules that Johnson’s assertion of “emotional injury” isn’t enough to transform his tort claims into personal injury ones. As such, Bernstein can weigh the value of Johnson’s claims. However, under what standard?

That leads to the second big issue. It’s one that Johnson wins and it’s a significant ruling that pertains to how anti-SLAPP laws function in federal courts.

SLAPP stands for “strategic lawsuit against public participation.” States like California have passed anti-SLAPP laws in an effort to bolster First Amendment activity by curtailing frivolous litigation intended to censor, intimidate and silence critics. An important aspect of anti-SLAPP laws is that judges get to address the merits of litigation early on in a case. In California, there’s also an automatic right to appeal SLAPP decisions. And the loser of SLAPP motions sometimes has to pay the winner’s legal bills. Added together, it provides some protection for media companies (and others) dragged into court on nuisance claims. It means that when these types of suits are filed, defendants have an out before litigation becomes too expensive and burdensome.

For the last few years, there’s been an attack on anti-SLAPP laws. Some plaintiffs have argued that under federal rules of civil procedure, plaintiffs only need to demonstrate the plausibility of claims before they’re allowed to proceed past a motion to dismiss. That’s a much lesser burden for plaintiffs than having to show the probability of claims succeeding under anti-SLAPP protocol.

In February, a Georgia judge rejected an attempt by CNN to strike a defamation lawsuit under Georgia’s anti-SLAPP statute. Even after hearing from the Motion Picture Association of America in an amicus brief, the judge decided that federal rules were the more important guidance. Only plausibility was necessary. That’s now under appeal, and earlier this month, 25 media organizations including ABC, Bloomberg, Comcast, Fox and The New York Times submitted an amicus brief urging the 11th Circuit to reverse the Georgia judge in the interest of fostering free speech. Meanwhile, in a decision last week by the 5th Circuit in a defamation case against The New York Times, that appellate circuit unnerved media lawyers by suggesting (if not definitively ruling) that state SLAPP laws don’t apply in federal court.

Now, as federal appellate courts around the nation grapple with the continued existence of state SLAPP laws, comes Bernstein’s latest decision in the Gawker bankruptcy. He quotes a concurring opinion from 9th Circuit Judge Alex Kozinski, who once wrote in a case involving Trump University, “The California anti-SLAPP statute cuts an ugly gash through this orderly process.”

In the opinion (read here), Bernstein agrees with SLAPP critics that California’s free speech law conflicts with federal rules. So when the bankruptcy judge ultimately weighs on Johnson’s claims, it will be on the plausibility standard. The SLAPP motion that Gawker filed against Johnson won’t matter. Johnson might still not be able to convince the judge his claims are worth much, but he’s got a better shot if he’s held to a lesser pleading standard.

More fundamentally, while this new opinion represents just one decision at a federal bankruptcy court, it’s likely to be cited by future litigants who face anti-SLAPP motions. Especially in New York, an important breeding ground of media.

Charles Harder, the attorney who once represented Hulk Hogan against Gawker, has been critical of the way anti-SLAPP laws allow automatic appeals and fee-shifting. Although he didn’t directly participate on the motion that was just decided, his Hogan suit may have just found its way to helping achieve this outcome.