Vestager and other Danish ministers on their way to meet Queen Margrethe, 2011.

Photographer: Linda Henriksen/Scanpix/Sipa USA

The Eurocrat Who Makes Corporate America Tremble

Apple. Google. Amazon. EU Competition Commissioner Margrethe Vestager has challenged them all.

One of the two commissioners anchoring the dialogue was Margrethe Vestager, the Danish politician who has found a heated celebrity as head of the EU’s directorate general for competition. Her job as chief sleuth requires her to protect the union’s vision of a fair market, and she’s set about it with gusto. Last August, Vestager announced that Ireland had granted Apple Inc. illegal tax benefits, and she directed the company to pay more than $14 billion in back taxes and interest. It was a rare boulder slung at a Goliath, and it drew cheers in many quarters in the U.S. and overseas.

Vestager’s entire tenure has been laced with an instinctive mistrust of big corporations. She’s driven investigations of Amazon.com, Fiat, Gazprom, Google, McDonald’s, and Starbucks—and she still has two and a half years remaining in her term. Rulings on McDonald’s and Amazon, both under scrutiny for their tax deals with Luxembourg, are imminent. If Vestager levies a multibillion-dollar fine against Google—a distinct possibility because the company is fighting three separate European antitrust cases—she will truly set headlines aflame. Google came under review for allegedly forcing Android phone manufacturers to pre-install its suite of apps, favoring its own comparison-shopping services in its search results, and preventing third-party websites from sourcing ads from its competitors. As with Apple and Amazon, these cases were bequeathed to Vestager by her predecessor, but she’s accelerated them to their finish lines.

Large American multinationals aren’t used to being stymied overseas, and Vestager’s consistent readiness to face off against them has provoked a startled fury. Tim Cook, Apple’s chief executive officer, called the tax decision against his company “total political crap.” And a group of 185 American CEOs appealed directly to European heads of government to reverse the ruling, describing it as “a grievous self-inflicted wound.” Even the U.S. government has felt the need to speak out. A white paper released by the Department of the Treasury last August criticized Vestager’s office for acting like a “supranational tax authority” and setting “an undesirable precedent.” In late March the office of the U.S. Trade Representative reiterated its opinion, as part of a broader report, that Vestager is deviating too far from prior case law. One former Treasury official from the Obama administration said Vestager’s staff resembled “a bunch of plumbers doing electrical work.”

Vestager – Photographer: Tine Claerhout for Bloomberg Businessweek

Vestager – Photographer: Tine Claerhout for Bloomberg Businessweek

None of this has dissuaded Vestager, who continues to defend one of the EU’s foundational philosophies: that a well-policed economy yields the largest and most widespread benefits for society. At a moment when the EU is convulsing with fresh doubt—impelled by Brexit, various species of populist nationalism, Greek frailty, Russian meddling, and a disenchantment with euro zone debt—Vestager has become one of the most visible, vocal champions of the union. This year she made Time magazine’s list of the world’s 100 most influential people. “I think she’s tough and serious,” Anthony Gardner, the U.S. ambassador to the EU from 2014 to 2017, says. “I would even call her a superstar.”

At the Black Diamond, she appeared from the wings with her Latvian colleague, Financial Stability Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis, and a moderator. A year shy of 50, Vestager radiates efficiency and self-control. She never slouches; her clothes—here a mustard-yellow dress, olive jacket, and boots—appear polished but comfortable, picked out for long working hours; not one movement is superfluous. Even her hair, dusted with more gray than black now, has been cropped short for years, as if to give her one less thing to do every morning. During the event, she was the picture of diligence. When the panelists sat down, she uncapped water bottles for them; when the moderator conducted a set of quick audience polls, she took photos of upraised hands; when Dombrovskis talked about Europe’s wind-power industry, she twisted in her chair to listen to every word, not looking away from him once.

In speaking about her work, Vestager is always fluently, adhesively on message. Even cursory attendance at her speeches and press events is enough to become familiar with her talking points. She frequently invokes the Treaty of Rome, which founded the European Economic Community 60 years ago, as a way of situating her office and its mission in the very headwaters of the EU. She likes to say Europe welcomes business of all kinds. “If you win on the market, that’s fair—we’ll congratulate you,” she said at the library. “But if you cheat on the way up, then that’s for us to look at.” Why wouldn’t companies want to be in Europe after all? “Europe is the best place to live on Earth, in history. Especially if you’re a woman.”

A tall man rose and introduced himself as a banker. The EU has had trouble inspiring much affection among its citizens, he said. “But here in Denmark, since Margrethe Vestager took over, the competition commission has become very close to people’s hearts.” Shouldn’t the EU reach out more, to become similarly beloved?

“It’s not in explaining the details or showing the process that you find acceptance,” Vestager said. “It’s in showing results, showing that it works. You don’t want to follow the baker in every step he’s taking. You just want to eat the pastry. We’re not asking people to love everything—just to love the big thing.”

Someone asked her if she’ll be warier of acting against American companies now that Donald Trump is president. The audience tittered uneasily, as Europeans tend to do at such events whenever Trump is mentioned.

Nothing would change, she replied. “We’re not going hard at U.S. companies specifically. It’s not your flag that matters to us. What really matters is: If you want to do business in Europe, you play by the European rule book.”

This was another of her well-worn aphorisms, but it masked the latest international wrinkles. Trump has already shown himself to be volatile on trade policy, reflexively defensive of U.S. interests, and an intermittent advocate of the collapse of the EU. His protectionist swagger has rattled Brussels; in March, Jean-Claude Juncker, the chief of the European Commission, warned that relations with Washington “have entered into a sort of estrangement,” and that any American tariffs on European products will trigger swift reciprocal action.

If this happens, Vestager’s office will become even more politically charged, liable to be deployed in retaliation and to attract even more American anger. By pursuing her cases with near-moralistic zeal, “Vestager has stuck her neck out quite a lot,” a lobbyist in Brussels says. “If there is a trade war with the U.S., she will be in the eye of the storm.”

Of course, boldness can reap political profit as well. One day in June 2008, when Vestager was the leader of a small Danish party called Radikale Venstre, she was stopped by a journalist in the corridors of the Parliament in Copenhagen. A suicide bomber had recently attacked the Danish embassy in Pakistan, and another politician had just observed that Denmark had now joined the ranks of the U.S. and Israel in being targeted by Islamic fundamentalists. Did she agree?

“Margrethe said, ‘If that’s correct, we need to change our foreign policy,’ ” Henrik Kjerrumgaard, her communications adviser at the time, recalls. “Before she came back to her office, it was all over the news.” It wasn’t just that she’d suggested distancing Denmark from putative allies, but that she’d considered altering policy in response to terrorism. Kjerrumgaard’s advice was to either apologize or defend her opinion. She defended, unwilling to admit she’d misspoken. “In Danish, we have a word, aerekaer. You’re concerned about your honor, about how people will see you,” Kjerrumgaard says. Vestager’s aerekaer makes her a formidable opponent—meticulous in preparation; so polite and reserved in conversation that it’s easy to underestimate how doggedly she’ll pursue her vision of right and wrong.

At the time of the embassy bombing, she had been leading Radikale Venstre for a year, during which the party was riven with infighting and invisible to the electorate. Her stance on the attack won her a lectern from which to expound her party’s other positions. Vestager had to grow into a comfort with boldness, though. “If your position is kind of blurry, and you don’t really know how to be approached, it’s very tricky to find a common position where you realize the compromises that you can make,” she says. It’s a paradox: “To make a good compromise, you have to have a strong starting position for people to know who they’re dealing with.”

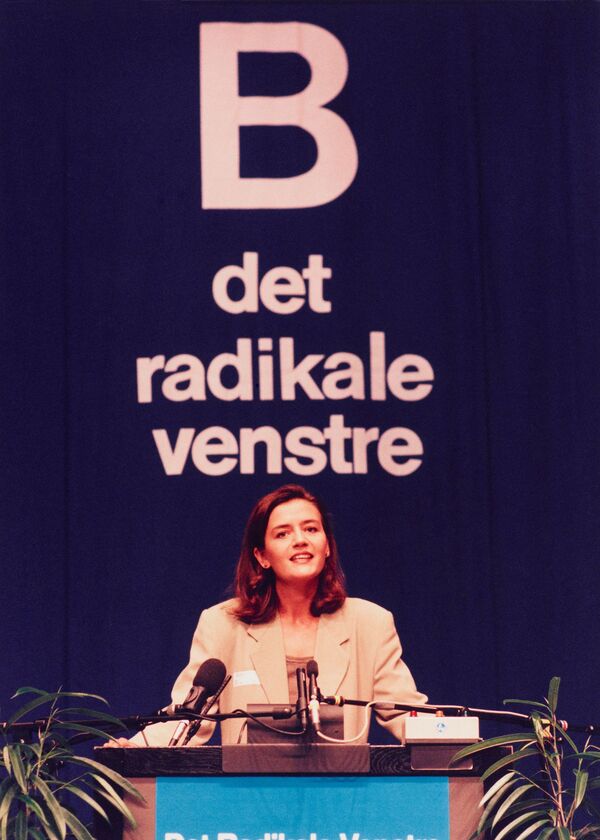

Speaking at Radikale Venstre, 1994. Photographer: Annelise Fibaek /Polfoto/Ritzau

Speaking at Radikale Venstre, 1994. Photographer: Annelise Fibaek /Polfoto/Ritzau

Vestager began her political career in 1988, at 20, working for Radikale Venstre—in direct translation, the “Radical Left,” though the party is habitually cast as the Social Liberals. Its principles are centrist, leaning toward economic conservatism. It’s small, more than a century old, happiest when playing kingmaker in parliamentary coalitions and indulging in policy wonkery. Vestager’s maternal great-grandfather helped found the party, and her parents were members. Her mother ran unsuccessfully for Parliament, and her father served in the municipal council in Varde, out on the peat bogs of the Jutland peninsula. Lutheran pastors both, the doors of their house were open to anyone who wanted to drop by for advice or spiritual succor. “They were very engaged in local society,” Vestager says. “That was the message I got and brought with me.”

Her parents’ stature in their town drew Vestager out of her natural reserve. “You grow up as kind of a public person,” says Elisabet Svane, her biographer. “In the summer, all the people from church would come home for coffee, and they’d be sitting in the garden—nearly 200 people. She was supposed to sit and talk to people. She didn’t like it. She hated it. But she liked to bring the coffee, do practical things.” Even today she has slim patience with chitchat, says Lars Nielsen, one of her friends.

Vestager rapidly shinned up the party’s ranks. When she was 29, she was put in charge of two ministries, education and ecclesiastical affairs, and served on several government committees; Radikale Venstre was transparently grooming her to lead it. Her reputation as a thorough but prickly—even callous—politician grew. Almost inevitably, she acquired the label “ice queen.” Nielsen describes Vestager’s fondness for applying her personal rule book to every sphere of politics and for the binary worldview that came of it: “We cannot negotiate here. Is it black or white? Is it A or B? Right or wrong?” He recalls the tale of a cabinet minister who thought he was approaching the end of a negotiation with Vestager when she decided that he had the wrong interpretation of a particular document page. She dressed him down as a teacher might an indolent student. “He thought it was part of her strategy. No, no—it was because he hadn’t done his homework,” Nielsen says.

Vestager with Thomas Steen Jensen at their 1994 wedding. Photographer: Nordfoto/Scanpix/Sipa USA

Vestager with Thomas Steen Jensen at their 1994 wedding. Photographer: Nordfoto/Scanpix/Sipa USA

In the fall of 2011, Vestager’s career reached a fulcrum. A conservative government, convinced it made fiscal sense to cut unemployment and early retirement benefits, staked its survival on the issues by calling fresh elections. Vestager supported the reforms, but she befuddled everyone by declaring her allegiance to an electoral alliance of left-leaning parties that were promising to roll back the austerity measures.

When the coalition won, Vestager and the leaders of her allied parties hunkered down in a hotel on the outskirts of Copenhagen to wrangle over policy details and cabinet positions. On the question of cutting welfare, she refused to back down—part of the reason the negotiations lasted three weeks. Everyone would get there at 8 a.m. or 9 a.m., Kjerrumgaard remembers, and spend the day bickering and confabulating, leaving for home only around midnight. He describes Vestager as a formidable negotiator. “She won’t ask ‘Is your coffee warm?’ or anything like that. She doesn’t care. She’ll just shut down and look at you.” She cleaves, he says, to the advice of one of her mentors: “Politics is about taking, not about giving.”

Vestager’s determination to slash welfare benefits might seem at odds with her current enthusiasm for challenging capitalism’s giants, and it’s tempting to conclude that her thinking shifted. But her nimbleness on economic policy reflects her party’s tradition of pragmatism—and, perhaps, her parents’ crisp ministering to their congregants’ difficulties.

At one point during those weeks in the hotel, Vestager realized she was in control of the parleys, and she made an audacious demand: the finance ministry for herself. As she expected, Helle Thorning-Schmidt, the prime minister-elect, declined. Vestager called the marriage off. “We went into our room, emptied it, packed our bags, and left the hotel,” Kjerrumgaard says.

After a day, he recalls, Vestager invited Thorning-Schmidt to her house. “She was controlling the venue—‘Come to me, have some pizza, let’s find a solution.’ ” Thorning-Schmidt offered Vestager a troika of titles—deputy prime minister, minister of the economy, minister of the interior—amalgamated into a single job just for her. The austerity measures remained in place. Four years after taking over a small, flailing party, the minister’s daughter had become the second-most powerful person in Denmark

Vestager’s European Commission office in the Berlaymont building in Brussels is large, comfortable, and awash with light. Her desk faces a window; she prefers to conduct meetings across a long table that bisects the room. Atop a side cabinet are dozens of framed photographs of her family: her husband, who teaches high school mathematics, and their three daughters. A cloud of cloth butterflies—made, she says, by Tibetan orphans—is pinned to the back wall. Her Fuck Finger is the centerpiece of a low coffee table.

The Finger—a fist with an upraised middle digit, cast in white plaster—is one of many aspects about Vestager that have become totemic during her rise to fame, known widely but also imprecisely. It’s commonly believed to have been sent to her by an infuriated Danish union when, as minister of the economy, she was pushing for austerity. The unionists actually gave it to her in a little ceremony of passive-aggressive respect at her office. She thanked them for participating in democracy, and they all drank beers and Cokes.

Incidents of this sort helped turn Vestager from a politician into a personality—a distinctive voice within the otherwise milquetoast chorus of Danish politics. The lead character in the televised Danish political drama Borgen—a dynamic prime minister, adept at navigating coalitions—is based on her, though she says she’s never seen the resemblance. Her relentless energy once worried her staff. “People feel stressed when they get updates about how you went out and ran 6 kilometers, baked buns, packed the kids’ lunchboxes, and went to an early meeting at 7:45 fresh,” Kjerrumgaard once told her. “Why don’t you say you fell in a puddle? Something that makes you human?”

With one of her three daughters, 1999. Photographer: JensNoergaard/Nordfoto/Scanpix/Sipa USA

With one of her three daughters, 1999. Photographer: JensNoergaard/Nordfoto/Scanpix/Sipa USA

Through the thick of the recession, Vestager struggled to revive Denmark’s economy. She presented two growth packages in two years and pared away welfare expenditures, never a warmly received move in her country. In 2012, trying to explain the inevitability of austerity, she let slip a stray remark—“That’s how it is”—that went viral; she was eviscerated for being uncaring and out of touch. That same year she chaired meetings of Europe’s economic and finance ministers. Relying in part on that experience, Thorning-Schmidt named Vestager to the European Commission in 2014, where Juncker put her in charge of competition.

Within the EU, the DG Comp—the directorate general for competition—considers itself an enforcement agency, wedded only to the rule of law and above the politicking that riddles the bureaucracy elsewhere. With the research capacities of a 900-strong staff, Vestager makes decisions related to cartelization and antitrust, approves or rejects mergers, and investigates state aid cases, in which member countries single out companies for unfair advantages such as tax breaks. In the U.S., state aid by way of targeted tax incentives is a legitimate strategy to lure investment; in Europe, it’s a forbidden tactic. That aside, the spirit of competition laws in the EU and the U.S. is identical; in its reckoning of what will impair the free market, though, the EU tends to exercise more caution than the U.S.

Commissioners come into their offices with varying objectives. “Vestager has made the tax investigations a very big priority indeed,” says Gert-Jan Koopman, a deputy director general in DG Comp. He disagrees with the perception that Vestager nurses a vendetta against American companies. The splashiest cases of her tenure—Amazon, Apple, and Starbucks—were all opened by Joaquín Almunia of Spain. “It’s very unreasonable to claim that she proactively decided to go after these companies,” Koopman says. The numbers bear this out. Of the 276 companies involved in antitrust cases opened by Almunia, 39 were American; in Vestager’s term, the breakdown is 11 of 81. Since state aid and tax cases technically concern EU member states, DG Comp doesn’t record the nationality of the companies involved. But over the past 15 years, of the 150 or so cases in which countries were directed to recover state aid they’d illegally doled out, fewer than 5 percent of the beneficiary companies have been American.

The friction between corporate America and DG Comp is in some manner cultural. American executives are often flummoxed when Vestager discusses competition law in the severe moral terms of a Biblical patriarch. “When we have a case and you take away the specifics and the technicalities of the law, what you find is basically the same as Adam and Eve,” she says. “It’s about greed—wanting to have something and taking a shortcut to get it. Or sometimes fear—fear of being driven out of the market if your competitors are growing into a strong position.”

Vestager makes it a point to abstain from glad-handing. She doesn’t, for instance, go to Davos, which transforms into Schmooze Central every year during the World Economic Forum. “In this portfolio, Davos is a little tricky,” she says. “People are more than welcome—CEOs if there is any issue—to come here for a meeting. In Davos, it’s something else.” She also refuses to meet lobbyists. Her office works best, she explains, when the consumer believes it to be fair—believes “that they haven’t decided the prices in the back office, they have not divided the market in some Gulf hotel over drinks.”

Meetings between American CEOs and competition commissioners can go badly. When Anthony Gardner worked for GE Capital in the early 2000s, the then-competition commissioner, Mario Monti, spiked GE’s merger with Honeywell International Inc. “Jack Welch had thought this was a political decision—he could slam his fist on the table and threaten retaliation. It’s counterproductive. It doesn’t work,” Gardner says. As ambassador to the EU, Gardner met often with visiting CEOs on their way to meet Vestager and gave them an informal lay of the land. “I was very clear with them. Don’t go in and lecture. It won’t work with her,” he says. “And what they should not do is engage in a public-relations campaign of slamming the commission, which has unfortunately happened in a few cases.” When Apple’s Cook visited Vestager in her office in January 2016, she was at her steely best, one witness to the meeting says. “I think Mr. Cook was more in a lecturing mode, and somehow they didn’t really connect terribly well.” (Apple declined to comment for this story.)

Being introduced as minister of ecclesiastical affairs, 1998. Photographer: Scanpix/Sipa USA

Being introduced as minister of ecclesiastical affairs, 1998. Photographer: Scanpix/Sipa USA

Vestager says the Apple case is, in its principles, no different from any other state aid investigation. Her declaration of Apple’s $14 billion-plus-interest tax bill flared brightly, she says, “because it’s a big number, and because it’s a company that everyone knows.” No state aid ruling has ever resulted in a recovery so enormous. In a March 2016 letter to Vestager, Cook wrote that he was concerned “about the fairness of these proceedings”; when the decision was announced, Apple and Ireland promptly appealed it. The money will be placed in escrow until European courts deliver a final decision, a process that’s likely to take years.

In the meantime, there will be other cases, other rulings. DG Comp is determining if Bayer AG’s $66 billion purchase of Monsanto Co. will make the EU’s agrochemical market anticompetitive. Vestager is also readying her decision on Luxembourg’s tax relationship with McDonald’s Corp., which could be ready before the European Commission breaks for the summer in August. Her investigation may already have forced McDonald’s to react; in December, the company announced it will shift its tax base to the U.K.

However insistent Vestager might be that her job involves a pure application of the law, it’s also inarguably informed by politics. It is, for example, a political virtue to demonstrate to euroskeptics—as she does—Brussels’s supervision of its member states and its resolve to protect the welfare of Europe’s citizens. Despite recent wins for Europhilic leaders in France, Austria, and the Netherlands, populists have found growing audiences in calling for their countries to follow the U.K. out of the EU. “Apple shows how you fight against populism,” a senior EU official told Reuters last September.

Vestager’s tenure and the Apple investigation have also coincided with a prolonged moment of discontent with the ethics of large corporations. “In general, there is a different sort of awareness and a legislative momentum on tax cases,” she says, attributing this attentiveness to the financial crisis and the tax-evasion revelations contained in the Luxembourg Leaks and Panama Papers episodes. “People have felt that benefits were cut in some member states, public salaries were cut maybe 10 to 15 percent—very hard-core decisions to get in control of your spending. And then, when people see that not all businesses contribute, I think the frustration and the anger about this have been largely underestimated.”

The EU’s best response to all this instability, particularly across the Atlantic, Vestager says, is to double down on its core values. “I don’t think Europe should be defined by the U.S. administration. We have so much going for us. This is a great place. It’s a wonderful place to do business.” In the choppy new world order, if the U.S. abandons its post at the tiller and retreats into itself, Vestager says, “Europe can step forward to fill whatever vacuum might appear.” There is no room for worry, no time to fret. “I think it’s more an obligation to be an optimist. Pessimism will never get anything done.”

—With Aoife White

___

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2017-05-10/the-eurocrat-who-makes-corporate-america-tremble