TMR Editor’s Note:

There is only one way to correctly understand exactly who the Founding Fathers were and that is to grasp their esoteric and true history. Even though many of them were Freemasons, that by no means indicates that they were not truly spiritual men and very high beings. In fact, they were the highest beings in the land. Freemasonry has not yet been taken over by the Illuminati when it was spreading throughout the 13 colonies in the 1700s.

Many of the Founding Father Freemasons were in fact devoted Deists and strong believers in God, except that they did not practice their faith the way that Christianity prescribed. Many of them left Great Britain so as to be free from organized Churchianity. It was freedom of religious expression and religious tolerance which actually drove many of them to the shores of America.

For more information on this matter the following extended essay teases out many of the historical facts and much of the hidden history … some of which CANNOT be found anywhere else on the Internet.

THE NEW ATLANTIS: Master Plan Of The Ages

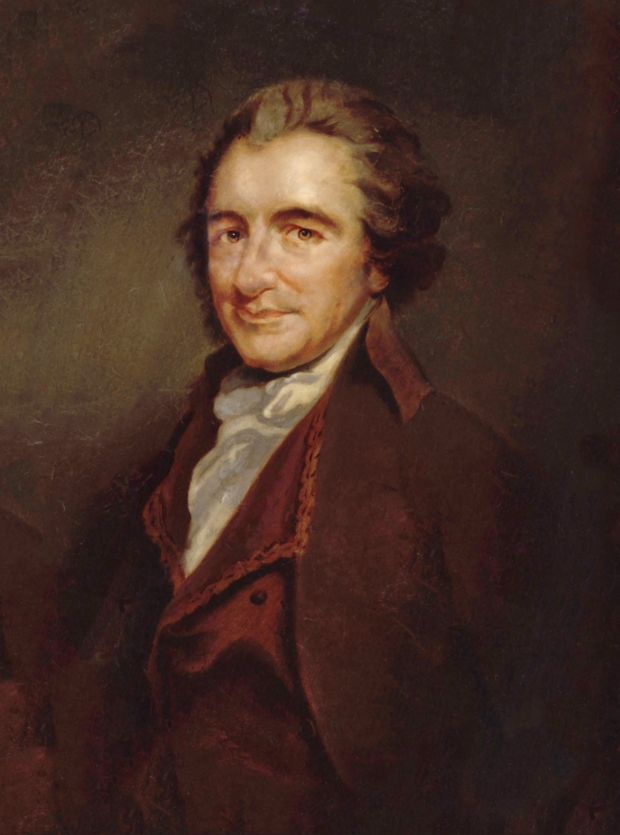

The critical point to keep in mind is that Thomas Paine was a deeply religious man (as was Thomas Jefferson) and a highly independent thinker for his day. It was his loathing of the ways in which organized religion was used to keep the populace in mental straightjackets that compelled him to leave the churches of his English homeland. He could see right through the quite purposeful manipulation to control the citizenry; hence, his permanent move from England to the fledgling American colonies in search of religious freedom.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION, PART II: WHO WROTE THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE?

And Was the Revolution a “Christian” War?

by James Perloff

I consider it prudent to begin this post by duplicating the first paragraphs of the foreword to Part I:

FOREWORD: I do not expect this two-part article to be very popular among American patriots, many of whom are my dear friends. They are among the core of America’s best citizens; men and women who fight to protect constitutional liberties from the police state, and to preserve U.S. national sovereignty from the tyranny of world government.

The following article raises questions about the American Revolution, which many patriots regard as the foundation of their beliefs. It can be dangerous to shake a good man’s foundation – even if the foundation is flawed – because it might cause him to question his worldview, and weaken his resolve. However, no historical event should be held so sacred as to be immune to examination. Our country is in too much trouble to make truth secondary.

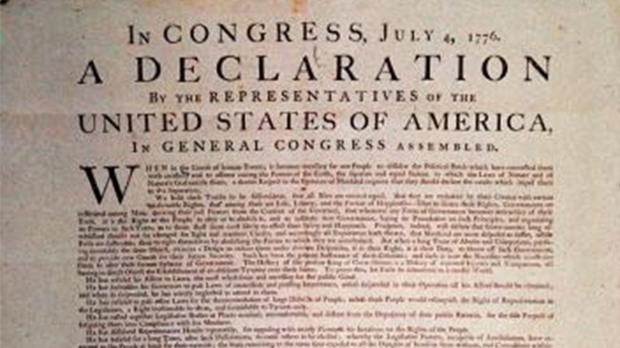

“Everyone knows” Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence, but not “everyone knew” it in early America. Jefferson was on the drafting committee at the Second Continental Congress. However, he made no claim to authorship until 1821, when he was an old man, and even then did so ambiguously.

Drafting committee: John Adams, Roger Sherman (said to be Freemason by descendants), Robert Livingston (Freemason, Grand Master of New York), Thomas Jefferson (believed to be a Rosicrucian), and Benjamin Franklin (Freemason, Grand Master of Pennsylvania) present the Declaration to the President of the Continental Congress, John Hancock (Freemason).

For a long time, it has been understood outside the box of orthodox historiography that the Declaration’s real author was Thomas Paine. The case was made, for example, in Junius Unmasked: Or, Thomas Paine, the Author of the Letters of Junius, and the Declaration of Independence, by Joel Moody (1872); in this article published by Walton Williams in 1906; and in Thomas Paine: Author of the Declaration of Independence by Joseph Lewis (1947).

Paine (1737-1809) was a British author of anonymous pamphlets. In England he met Freemasonic Grand Master-at-large Benjamin Franklin (who served not only as Grand Master of Pennsylvania, but Grand Master of the Nine Sisters Lodge in Paris, as well as attending Britain’s satanic Hellfire Club). When Paine traveled to America, Franklin gave him a letter of introduction. He arrived on November 30, 1774, greeted by Franklin’s physician. This was less than five months before the orchestrated Battle of Lexington, flashpoint of the Revolutionary War.

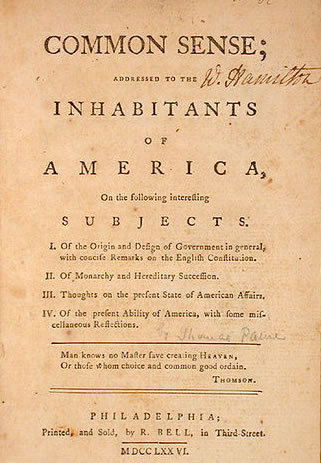

Paine wasted little time fulfilling a mission is his new-found land. In 1775 he wrote the lengthy pamphlet Common Sense, which called for America’s independence from Britain. Widely distributed, it became the single most influential document inspiring the revolution. Inscribed at Paine’s gravesite is John Adams’s famous rhyme: “Without the pen of Paine, the sword of Washington would have been wielded in vain.”

Could Paine’s overnight literary success in America have occurred without “helping hands”?

The Declaration of Independence fulfilled the objective of Common Sense. Paine was residing in Philadelphia when the Second Continental Congress met there. As Franklin’s choice to write Common Sense (which he authored anonymously), would he not also be the logical choice to anonymously write the Declaration? As we will soon elaborate, there were several reasons why this could never be publicly disclosed.

The Case for Paine

First, though, let’s review some of the evidence that Paine authored the Declaration. A blog post can only examine a sampling; for thorough analysis, I recommend consulting the sources named above.

There is, of course, a copy of the Declaration in Jefferson’s handwriting. However, there is also one in John Adams’s handwriting. These are evidently copies of Paine’s original. Both content and style are markedly like Paine, not Jefferson, who had never written any paper calling for American independence.

• The original, unedited version contained an anti-slavery clause:

He [King George III] has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the CHRISTIAN king of Great Britain. Determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought & sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce . . . .

It is commonly said that Jefferson wrote this passionate clause, and slave owners at the Congress demanded its deletion. However, this makes no sense. Jefferson was himself a slave owner; he owned over 600 during his lifetime. And in his writings up to the time of the Declaration, he had never composed even a mild denunciation of slavery.

Paine, on the other hand, had published a 1775 essay called African Slavery in America, writing, e.g.:

That some desperate wretches should be willing to steal and enslave men by violence and murder for gain, is rather lamentable than strange. But that many civilized, nay, Christianized people should approve, and be concerned in the savage practice, is surprising. . . .

Our Traders in MEN (an unnatural commodity!) must know the wickedness of the SLAVE-TRADE, if they attend to reasoning, or the dictates of their own hearts: and such as shun and stiffle all these, wilfully sacrifice Conscience, and the character of integrity to that golden idol. . . .1

Note the capitalization of “MEN” in both Paine’s tract and the Declaration’s anti-slavery clause!

• The Declaration exhibited undisguised disdain for King George III:

The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.

A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Such scorn was characteristic of Paine, who called him “the Royal Brute of Great Britain” in Common Sense, which also contained remarks such as these:

I rejected the hardened, sullen-tempered Pharaoh of England forever, and disdain the wretch, that with the pretended title of FATHER OF HIS people can unfeelingly hear of their slaughter, and composedly sleep with their blood upon his soul.2

the naked and untutored Indian, is less savage than the King of Britain.3

Compare that to Jefferson’s tract A Summary View of the Rights of British America, in which he consistently referred to King George by the respectful title “his Majesty.” Extract:

to propose to the said Congress that an humble and dutiful address be presented to his Majesty, begging leave to lay before him, as Chief Magistrate of the British empire, the united complaints of his Majesty’s subjects in America . . . . which would persuade his Majesty that we are asking favors, and not rights, shall obtain from his Majesty a respectful acceptance; and this his Majesty will think we have reason to expect, when he reflects that he is no more than the chief officer of the people. . . .4 [Italics added]

• The Declaration, including the original draft, uses the word “hath”:

all experience hath shown that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.

Why is this significant? Because in all his individual writings, Jefferson never once used the archaic word “hath,” preferring “has.” Paine, however, used it frequently—in Common Sense, for example, he used “hath” 87 times.

• The Declaration’s original draft condemned the use of “Scotch and foreign mercenaries.” In the final version, the words “Scotch and” were stricken out by the Congress. Why would Jefferson have denounced the Scotch? He traced his own ancestry partly to Scotland, had Scottish teachers during his education, and was affectionate toward Scotsmen. But Paine’s s writings in England had expressed bitter disdain for them.5

Many other examples can be found in the above-cited works: frequent use of capitals in the Declaration—habitual for Paine, but not Jefferson; the correlation of parts of the Declaration with passages in Common Sense; etc.

The Silence Explained

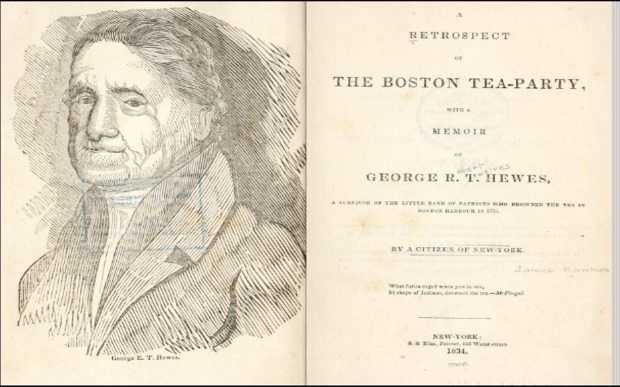

Much of the American Republic’s history is surprisingly shrouded in secrecy. All the men who took part in the Boston Tea Party swore a 50-year oath of silence.6 This is why no participant published a description of it until George Hewes’s memoir in 1834.

In my post The Secrets Buried at Lexington Green, we explored the fact that Americans firing shots at Lexington was also kept publicly secret until 50 years after the event.

Was there also, then, a 50-year oath of silence regarding the Declaration? Thomas Jefferson dropped no hint of authorship for 45 years. Finally, in 1821 he recalled:

The committee were J. Adams, Dr. Franklin, Roger Sherman, Robert R. Livingston & myself. Committees were also appointed at the same time to prepare a plan of confederation for the colonies, and to state the terms proper to be proposed for foreign alliance. The committee for drawing the declaration of Independence desired me to do it. It was accordingly done, and being approved by them, I reported it to the house on Friday the 28th of June when it was read and ordered to lie on the table.7

“It was accordingly done” is not a very emphatic claim to authorship. If there was a 50-year oath of silence associated with the Declaration, it might be noteworthy that that both Jefferson and John Adams died on the exact day it would have expired: July 4, 1826. I have always romanticized that coincidence, and perhaps it should just stay romanticized. In any event, Jefferson said nothing about writing the Declaration until after Paine’s death.

But why couldn’t Paine be acknowledged as the Declaration’s author? Three reasons stand out:

• The Declaration was supposed to be written by elected delegates, something Paine was not.

• Since Paine hadn’t lived in the colonies before November 30, 1774, it was debatable if he could even be described as an “American.” Although his allegiance to the revolutionary cause might certainly have merited that characterization, most Americans would have been surprised to learn their Declaration was penned by someone who had resided so briefly on their continent. (Paine later returned to Europe, living there from 1787 until 1802.)

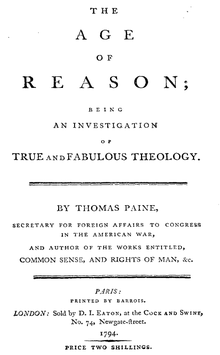

• But the most important reason Paine couldn’t be acknowledged was that he later wrote The Age of Reason, in which he bitterly denounced Christianity.

Extracts:

It is the fable of Jesus Christ, as told in the New Testament, and the wild and visionary doctrine raised thereon, against which I contend.8

Of all the systems of religion that ever were invented, there is none more derogatory to the Almighty, more unedifying to man, more repugnant to reason, and more contradictory in itself, than this thing called Christianity.9

I have shown in all the foregoing parts of this work, that the Bible and Testament are impositions and forgeries.10

I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish Church, by the Roman Church, by the Greek Church, by the Turkish Church, by the Protestant Church, nor by any Church that I know of. My own mind is my own Church.11

Since America was predominantly Christian, it couldn’t be admitted that someone of such views had penned the nation’s birth certificate. It would have caused what we now call “cognitive dissonance.”

NOTES

- Thomas Paine, African Slave Trade in America, http://constitution.org/tp/afri.txt.

- Thomas Paine, Common Sense (1775; reprint, Girard Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Co.), 49.http://archive.org/details/commonsense00painrich.

- Daniel Edwin Wheeler, ed., Life and Writings of Thomas Paine (New York: Vincent Patke and Co., 1908), 79.

- Thomas Jefferson, A Summary View of the Rights of British America (1774),http://www.history.org/almanack/life/politics/sumview.cfm.

- Joseph Lewis, Thomas Paine: Author of the Declaration of Independence (New York: Freethought Press, 1947), 284-87.

- Thom Hartmann, What Would Jefferson Do? A Return to Democracy (New York: Three River Press, 2004), 44.

- Joyce Appleby and Terence Ball, ed., Jefferson: Political Writings (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 95.

- Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason (1794-95; reprint, London: Freethought Publishing, 1880), 115. http://archive.org/details/ageofreason00painiala.

- Ibid., 147.

- Ibid., 152.

- Ibid., 2.

- Thomas Paine, “Of the Word Religion,” The Theological Works of Thomas Paine (New York: William Carver, 1830), 337.

- Paine, Age of Reason, 16.

- Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 1 (London: British and Foreign Public Library, 1818), xxxv-xxxvi.

- Thomas Hutchinson, Strictures upon the Declaration of Independence (1776),http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/1776-hutchinson-strictures-upon-the-declaration-of-independence.

- William H. Hallahan, The Day the American Revolution Began: 19 April 1775 (New York: HarperCollins, 2001), 254.

- Nesta H. Webster, Secret Societies & Subversive Movements (1924; reprint. Brooklyn, N.Y.: A & B Publishers Group, 1998), 241-42.