Economic war: Venezuela food shortages deliberately created by US-aligned oligarchs

Billionaire Lorenzo Mendoza runs Venezuela’s largest food company, Empresas Polar. A constant threat to murdered Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, current President Nicolas Maduro has called him an “oligarch of the devil” and has accused him of reducing production and hoarding products to create shortages.

Private sector wholesalers and retailers resist selling at controlled prices so that they can make much larger profits elsewhere.

The Symptoms

This week, the Venezuelan government began raising the controlled prices of several essential food items and other basic goods. The aim is to make it’s more worthwhile for producers, wholesalers or retailers to sell them, and thereby reduce the incentive to hoard them or divert them onto the parallel, informal market where they go for many times their official price.

In our previous article, we mentioned this elaborate system of bachaqueo, or reselling. It is the most glaring expression of the food problem in Venezuela, it fuels both the shortage of basic goods, and their exorbitant price.

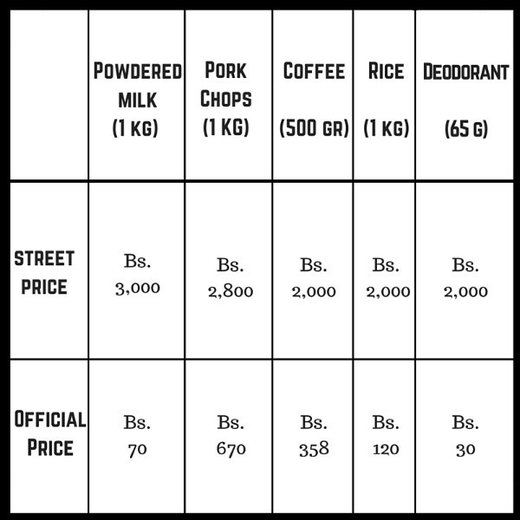

The figures speak for themselves. In the last half of April, these were some of the prices that the bachaqueros were selling goods for in the poor area of Petare, in the east of Caracas:

There are other mechanisms that divert these goods from supermarkets and corner shops, like smuggling abroad and hoarding. But the basic principle is the same. Private sector wholesalers and retailers, as well as corrupt elements in the public system, resist selling at controlled prices, so that they can make much larger profits elsewhere.

But these are just the symptoms. What really lies behind all of this?

Has the Government Neglected Production?

The Venezuelan opposition’s parliamentary report on the food situation in the country – the one it drew up to back its claim that there is a humanitarian crisis and seek international intervention – has a fairly simple argument to explain the shortages. The Bolivarian government allowed domestic production to collapse and relied too much on imports. Now it has less dollars to import with, that problem has turned into a crisis.

This argument contains a grain of truth but it is incomplete, to put it mildly.

Venezuela’s inability to produce goes back decades. From the middle of the last century, the world’s number one oil exporter abandoned agriculture and most of its high quality arable land lay idle. By the time Hugo Chavez came to office, only about 9 percent of the population lived on the land, far below the average in Latin America.

In 2004 and 2005, after winning the recall referendum against him, Chavez launched an offensive to boost local production. “Endogenous development” went hand in hand with declaring that the Bolivarian revolution was heading toward socialism. Land reform began in earnest. Mission Vuelvan Caras began to train the urban poor in agricultural and other skills. Tens of thousands of cooperatives were set up. Almost all of these failed.

The reasons were many, but one of the most potent was that oil prices began to rise sharply. It was just so much easier to import everything, than to build a whole new system of production. And with more people consuming much more, there was a lot that needed to be imported.

The Great Import Scam

This presented Venezuela’s traditional elite with an unexpected opportunity. For they still owned most of the companies that did the importing. Since losing control over the state oil company, they had been desperate to claw back their share of its income.

They set about developing one of the greatest scams of all time. It was based on acquiring cheap dollars from the Central Bank for false or manipulated imports, and then speculating on the growing gap in exchange rates.

This is how it worked. Private importer Mr. A applies for US$ 1,000 to import 100 cases of groceries. This costs him 6,300 bolivars (at the government’s main preferential rate of US$ 1.00 = Bs. 6.30, in place until earlier this year). Mr. A then has several options. He could decide actually to import all 100 cases. But instead of selling them to his wholesalers at a price based on what he paid, US$ 10 or Bs. 63 per case, he sells them at a price based on the illegal, parallel exchange rate (US$ 1.00 = Bs. 500.00, early last year), that is Bs. 5,000 per case. In other words, he makes a killing in bolivars. But it is much more likely that Mr. A imports only 50 cases, or less, which he sells in the same way and still makes a handsome profit. With the rest of the dollars he was given, 500 or more, he can do several things. He can change them back into bolivars at the parallel rate, but he’d probably rather keep them for a while offshore until the rate goes up even further. Or invest them in something else abroad. Or keep them in his own private dollar account for a rainy day. In other cases, Mr A didn’t import anything at all. He basically stole all of the dollars.

Big private companies in Venezuela did the same thing on a much larger scale. In 2013, the then head of the Venezuelan Central Bank, Edmee Betancourt, said that the country had lost between $15 and $20 billion dollars the previous year through such fraudulent import deals. The Central Bank’s own figures show that between 2003 and 2013, the Venezuelan private sector increased its holdings in foreign bank accounts by over US$ 122 billion, or almost 230 percent. In 2014, Chavistas campaigning for an audit of the public debt estimated the total amount lost over the same period through fake imports and similar mechanisms amounted to an incredible US$ 259 billion.

It is likely that many of the 750 offshore companies linked to Venezuela in the database released from the Panama Papers have been used to recycle this money.

Venezuela’s largest food manufacturer, Polar, has interrupted production several times in recent weeks because, it says, the government hasn’t given it the dollars it needs to import its raw materials. But over the years, Polar has been one of the very biggest recipients of preferential dollars for imports. And from somewhere it has found enough dollars to develop new production facilities in the United States and Colombia.

The Real Economic War

These are the underlying mechanisms that have driven both the shortages and the runaway inflation that Venezuelans now have to live with. As Neftali Reyes, a critical Chavista activist and analyst told teleSUR, “the bachaqueo and smuggling are just a consequence of all this.”

You can criticize the Bolivarian government for its part in this, and many Chavistas do: for policies that failed to prevent or correct it, or for complicity and corruption at many levels. But it is clear that it is Venezuela’s private business and financial sector that has driven this process from the start. And if the figures quoted above are even half right, very few of these businessmen seem to be the earnest but frustrated “producers” depicted in the opposition’s parliamentary report.