One-Third Of The World’s Largest Groundwater Sources Are In Serious Trouble: Study

The Huffington Post | By Hilary Hanson

BAKERSFIELD, CA – FEBRUARY 6: Workers drill for water for a farmer on February 6, 2014 near Bakersfield, California. Now in its third straight year of unprecedented drought, California is experiencing its driest year on record, dating back 119 years and possible the worst in the past 500 years. Grasslands that support cattle have dried up, forcing ranchers to feed them expensive supplemental hay to keep them from starving or to sell at least some of their herds, and farmers are struggling with diminishing crop water and whether to plant or to tear out permanent crops which use water year-round like almond trees. About 17 rural communities could run out of drinking water within several weeks and politicians are pushing to undo laws that protect several endangered species. (Photo by David McNew/Getty Images)

The earth’s biggest groundwater basins are being depleted far more quickly than previously believed, according to two new studies by the University of California, Irvine (UCI).

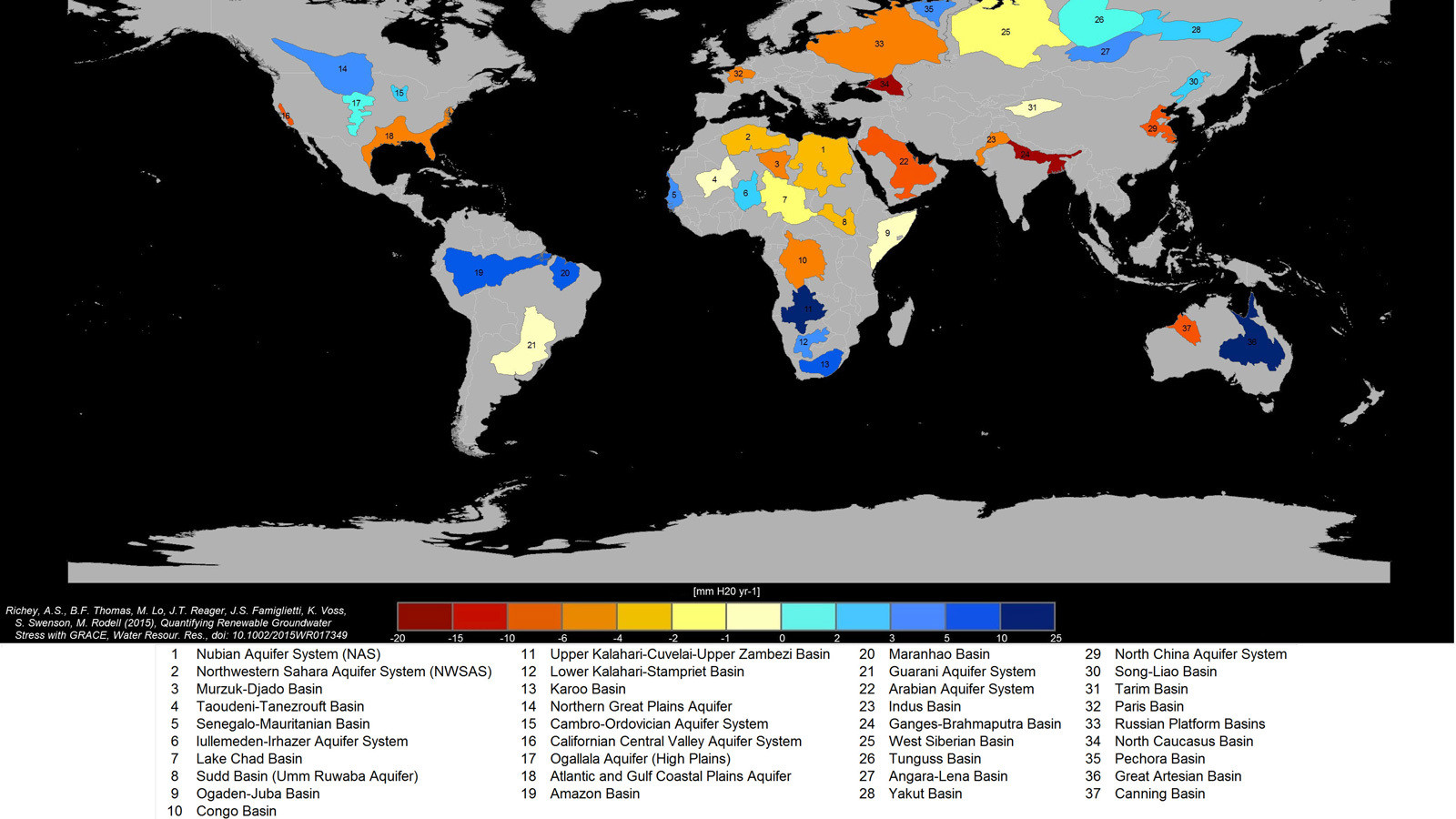

The studies used data from NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites gathered between 2003 and 2013 to examine the 37 largest aquifers on the planet. Twenty-one of those aquifers have exceeded their sustainability “tipping points,” meaning they lose more water every year than is being naturally replenished through processes like rainfall or snow melt, said Jay Famiglietti, senior water scientist at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and principal investigator in the two studies.

Out of those 21, eight were found to be “overstressed,” meaning there is “nearly no natural replenishment” to restore water used by humans, according to a statement from UCI. Another five were designated “extremely or highly stressed,” signifying that they are “still in trouble” but have “some water flowing back into them.”

The world’s most overstressed groundwater source, according to researchers, is the Arabian Aquifer System, which supplies water for more than 60 million people.

Researchers used readings from NASA’s two GRACE satellites, which measure variations in the earth’s gravitational pull, Famiglietti told The Huffington Post. When an area either gains or loses a large volume of water, the change in mass allows the satellites pick up the difference in the gravitational pull. This lets researchers determine the rate at which large aquifers are being depleted.

Though scientists are able to tell how quickly the water is being depleted, they do not know exactly how much is left.

It would be possible to determine the present groundwater supply by drilling into the aquifers, Famiglietti said, but scientists currently lack the funding to do so.

He believes it’s crucial to determine the exact amount of water still in the ground.

“Given how quickly we are consuming the world’s groundwater reserves, we need a coordinated global effort to determine how much is left,” he said in the UCI statement.

Read the full studies, which were published Tuesday in Water Resources Research,here and here.