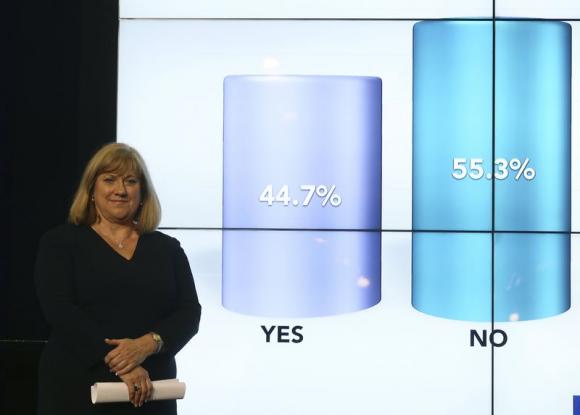

The chief counting officer for the referendum, Mary Pitcaithly, poses for photographs after announcing the final results of the Scottish vote for independence, in Edinburgh, Scotland September 19, 2014.

EU relief at Scotland’s “no” tinged with fear of nationalism

BY ALASTAIR MACDONALD AND PAUL TAYLOR

REUTERS

(Reuters) – European Union and NATO officials expressed undisguised relief on Friday at Scotland’s clear vote against independence from Britain, but some fretted that the genie of separatism may be out of the bottle in Europe.

EU partners had mostly kept quiet in the run-up to Thursday’s referendum, lest their fears of a break-up of the United Kingdom leading to contagion elsewhere in Europe be seized upon as interference.

But as soon as the Scottish “No” was secure, they voiced satisfaction and drew consequences for their own countries, for the 28-nation EU and for the Western alliance.

NATO Secretary-General Anders Fogh Rasmussen congratulated British Prime Minister David Cameron and said he was sure the United Kingdom would continue to play a leading role in keeping the U.S.-led defence alliance strong.

Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, struggling to quash an independence drive by the northeastern region of Catalonia, said the Scottish result was the best outcome for Europe.

“The Scottish have avoided serious economic, social, institutional and political consequences,” he said in a video message posted on the government website. “They have chosen the most favourable option for everyone; for themselves, for all of Britain and for the rest of Europe.”

Undeterred, Catalan regional president Artur Mas vowed on Friday to press ahead with plans for a non-binding referendum on independence on Nov. 9, which the Spanish government says would be illegal.

Madrid won support from German Chancellor Angela Merkel on Friday when her spokesman, commenting on the Scottish vote, said Catalonia was “a completely different legal situation” and she supported Rajoy’s position.

Merkel herself, who had voiced a preference for keeping Britain together, told reporters the Scottish referendum should not have any direct consequences elsewhere but she respected the outcome – “and I say that with a smile”.

The European Commission said the Scottish vote was good for a “united, open and stronger Europe” – a veiled message that EU officials hope it will strengthen chances of Britain voting to stay in the bloc in a promised referendum in 2017.

“The European Commission welcomes the fact that during the debate over the past years, the Scottish government and the Scottish people have repeatedly reaffirmed their European commitment,” Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso said.

“CATACLYSMIC”

Belgian EU Trade Commissioner Karel De Gucht, whose native Flanders region is in thrall to a growing nationalist movement, said a Scottish split would have been “cataclysmic” for Europe, triggering a domino effect across the continent.

“If it had happened in Scotland, I think it would have been a political landslide on the scale of the break-up of the Soviet Union,” said De Gucht, a liberal who does not support demands from some of his fellow Flemings for their own state.

“A Europe driven by self-determination of peoples … is ungovernable because you’d have dozens of entities but areas of policy for which you need unanimity or a very large majority,” he said, adding that “parts of former countries” might behave in a very nationalistic ways.

Even before Scottish polls closed, French President Francois Hollande expressed his fear of a possible “deconstruction” of Europe after decades of closer integration.

“That is what is happening at the moment, this conjunction of centrifugal forces that is losing sight of the European objective,” he told a news conference on Thursday, citing a danger of the break-up of the EU and individual member states because they were no longer seen as protecting citizens.

France is one of the EU’s most centralised states, with little support for independence movements in Corsica, Brittany and the Basque Country. But other member states such as Spain, Italy and Belgium face bigger pressure for decentralisation.

Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi underlined how the Scottish vote raised hopes that a united but more decentralised Britain would remain in the European Union.

“The value of diversity and the riches of our territories, not fragmentation, is the answer which the Scottish people, rightly proud of their history and traditions, has given to all of us,” he said.

“The European Union will certainly benefit from a renewed commitment by the United Kingdom to reinforcing our joint action to provide concrete answers to the justified desire of our citizens for economic development and a capacity to face our many international challenges,” Renzi said.

The president of the European Parliament, German Social Democrat Martin Schulz, said separatist movements in Europe were often fuelled by “social inequality and a wealth gap, where richer regions say we don’t want to pay to support other regions”, as well as by unemployment and rural poverty. The EU needed to address those underlying causes, he said.

“NOT ENTIRELY MAD”

Czech Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka said the Scottish result made him happy because “I take it as yet another proof that the world has not gone entirely mad.”

If Britain had fallen apart, it could have led to a wave of nationalism that would have destabilised a number of other European countries, Sobotka said.

However, several European policymakers speaking on condition of anonymity said Scotland had also set a precedent of regions’ having a democratic right to vote on independence, which could be problematic in Spain and elsewhere.

While the Scots’ vote may settle the issue of separation in Britain for a generation, as Cameron said, it will also cause constitutional upheaval with much greater devolution of power in the UK, and may whet appetites across Europe.

Northern Ireland nationalist leader Gerry Adams said Scotland’s “inspiring” referendum would accelerate a vote to unite Ireland, a prospect dismissed by Unionists who share power with his Sinn Fein party in Belfast. The province, dominated at the time by Protestants, remained part of the United Kingdom when largely Catholic Ireland secured independence in 1921.

The 1998 Good Friday peace agreement which ended decades of sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland permits a referendum every seven years.

Former German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher, who helped negotiate German reunification in 1990, said the vote showed that strongly centralised government was out of favour on the continent.

“Germany’s model of a federal system with a central government and independence for the states and municipalities is the more modern system,” he said.

(Additional reporting by Philip Blenkinsop and Adrian Croft in Brussels, Sonia Dowset in Madrid, Emmanuel Jarry in Paris, Stephen Brown in Berlin, James Mackenzie in Rome and Robert Muller in Prague; Writing by Paul Taylor; Editing by Sophie Walker)