The G-20’s Solution To Systemically Unstable, “Too Big To Fail” Banks: More Debt

ZeroHedge.com

It’s been 6 years since Lehman went bankrupt overnight, stunning bondholders who were forced to reprice Lehman bonds from 80 to 8 (see chart below) in a millisecond, and launching the world’s worst depression since the 1930s, which courtesy of some $10 trillion in central bank liquidity injections, has been split up into several more palatablefor public consumptions “recessions”, of which Europe is about to succumb to the third consecutive one even if for the time being the Fed’s has succeeded in if not breaking the business cycle, then certainly delaying the inevitable onset of the next major contraction in the US economy.

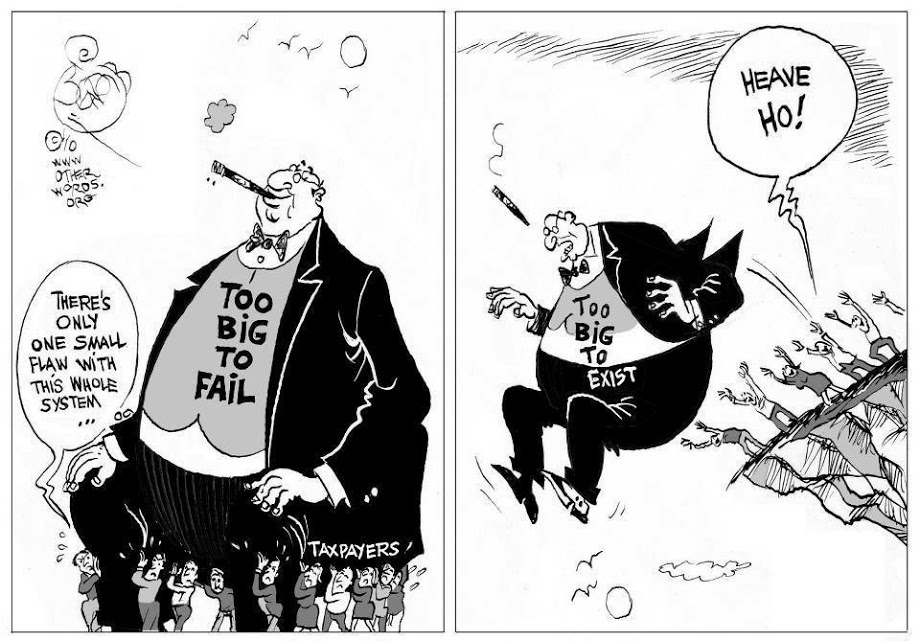

Paradoxically, instead of taking advantage of this lull in volatility and relative economic calm, and making the financial system more stable, all so-called regulation has done, is paid lip service to the underlying problems, hoping that should the next crisis appear the Fed will be able to delay it yet again by throwing countless amounts of taxpayer money at the problem. In the meantime, the biggest banks have gotten so big that the failure of one JPM or Deutsche Bank, and their hundreds of trillions in gross notional derivatives, would lead to the biggest financial and economic catastrophe ever witnessed and make 2008 seem like a fond memory of economic euphoria.

So finally, with a 6 year delay, the western world’s “government leaders” have finally decided to do something about a TBTF problem that has never been more acute. According to Reuters, in November said leaders will agree “that the world’s top banks must issue special bonds to increase the amount of capital which can be tapped in a crisis instead of calling on taxpayers to come to the rescue, industry and G20 officials said.” In other words, suddenly the $2.8 trillion in Fed injected excess reserves, split roughly equally between US and European banks, are no longer sufficient, and while regulators are on one hand delaying the implementation of Basel III and its tougher capital rules, on the other they are tacticly admitting that whatever “generous” capital buffer banks have on their books right now will not be sufficient when the next crisis strikes.

Enter GLACs.

The bonds which will be issued by the top banks known as “gone concern loss absorption capacity” or GLAC, are seen by regulators as essential to stopping the world’s 29 biggest lenders from being “too big to fail.”

We will have some more to say on the “irony” of that statement in a moment, but here is the punchline – according to the G-20, instead of having to collapse liabilities to offset that scourge of the New abnormal, namely Non-Performing Loans, banks are hoping to lever up, pun intended, the current scramble for yield and instead beef if up their cash asset, even if it means increasing the liability side of the balance sheet by issuing more debt. Because really all the GLAC do is limit how the banks may use the proceeds from such bond issuance. Then again, these being banks, one can be certain that the moment the GLAC cash is wired in, the funds will be used to ramp risk instead of sitting in a drawer somewhere, awaiting rainy days. Because nobody in a bank is paid for avoiding a crisis, and everyone is paid to generate a return even if it means making the systemic bubble even bigger.

The plans are being drafted by the Financial Stability Board, the regulatory task force of the Group of 20 economies which declined to comment ahead of a G20 summit in November, when G20 leaders will discuss the reform before it is put out to public consultation.

The reform would put in place the final major piece of G20 regulation on banking as the global body turns to a “post-crisis” agenda of fostering economic growth and bedding down the rules it has approved.

There had been unease in Asia and parts of Europe over how big the bond issues need to be to provide this cushion but there is now a new optimism amongst bankers and regulators that the G20 will reach a deal in November.

What is unsaid is that the “unease” was there because banks were unsure there would be enough risk appetite for such bond issuance. But now that the central bank credit bubble is so immense it allows Ebola-stricken African nations to issue bonds at a 7% yield, there is nothing preventing the banks from merely funding their way to stability.

Of course, one has to be an idiot at this point and observe that the “risk buffer” would have to come from retained earnings, not from more debt, the source of the risk in the first place. However in a world in which banks can’t generate either the required GAAP earnings and certainly cash flows, to build said buffer, the G-20 will hope that everyone is dumb enough not to comprehend the fundamental flaw in this brilliant plan.

Speaking of the plan, it continues:

“The industry is definitely in favor of making resolution, supported by an appropriately flexible concept of GLAC, work. That is the key pending aspect on ending too-big-to-fail,” said Andres Portilla, director of regulatory affairs at the Institute of International Finance, a Washington-based banking and insurance lobby.

So according to Mr. Portilla, the solution to a TBTF problem resulting from record amounts of debt is more debt? Ok, just making sure everyone got that.

“What is likely to happen is that there will be a consultative proposal, but without all the detail that a lot of people would like,” Portilla added.

However, a G20 source said a deal was not only expected but would also be more detailed than some parties anticipate, which is essential for conducting a thorough impact assessment before finalizing the rules. “The authorities and the FSB are working to have a proposal that will contain sufficient granularity of numbers to be a meaningful consultation and quantitative impact study to calibrate the final rule,” the source said.

Top banks expect they will have to hold GLAC bond capital equivalent to about 10 percent of their risk-weighted assets on top of their core capital buffers which currently stand at around 10 percent. But they hope for some leeway if they can show that they can already be wound down smoothly in a crisis because of simplified structures.

The G20 source poured cold water on this, saying regulators believe all the world’s top 29 banks earmarked for tougher supervision will need a significant cushion of such so-called “bail-in” bonds for some time to show they can be shut without public aid.

Regulators ultimately want to price bank debt better and end the cheaper funding that too-big-to-fail banks enjoy because markets assume governments would never allow them to collapse.

And the hilarious conclusion:

“Adopting GLAC is the final chapter in reforming the condition of banks,” said Thomas Huertas, a former UK banks supervisor and now a regulatory consultant with EY.

The plans for bail-in bonds are among the last of what G20 officials call the “heavy lifting” on banking industry reforms that came in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

So, to summarize: in lieu of being able to actually generate and retain funds from operations, banks will once again scramble to raise epic amounts of debt, only this time, the proceeds will be retained “pinky swear” as a capital buffer, i.e., cash on the books. Cash which nobody makes a single dime in bonus on anywhere in the bank’s org chart. Would anyone wish to wager how long before the trillions in GLACs are “mysteriously” found to have funded shanty town developments in Shanghai, to buy the S&P500 at the all time high, and naturally, the purchase of a golden commode or two in various US banks? How could this possibly fail…

And the absolutely brilliant punchline: who do these regulators and “leaders” think will be the purchasers of said debt? Why other systemically important, TBTF banks of course! Which means that, in the by now quite familiar “daisy-chaining” of counterparties and collateral, once one bank fails, its exposure via collateral, repo and certainly, funding of other bank balance sheets, everything will promptly freeze as risk reprices, a la Lehman bonds.

Because if one thing is certain when one bank’s liabilities are another bank’s assets, it is that such an arrangement is simply screaming for a systemic crisis to prove to everyone just how dumb this idea was from the get go.

And another certain thing: the only entity on the hook when this plan unravels like a house of cards the second a bank with a few trillion in “assets” collapses, will be the same one as always: the taxpayer. Only this time the total amount that will be handed over to the bankers who control the central banks pulling the strings of the next bail out, will be that much bigger, or X+GLAC for those mathematically inclined.