Is There Capitalism After Cronyism?

Charles Hugh Smith

oftwominds.com

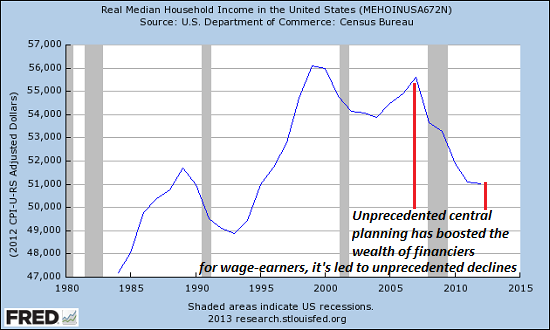

The more the Status Quo pursues the same old Keynesian Cargo Cult script of central planning and free money for financiers, the more self-liquidating the system becomes.

Judging by the mainstream media, the most pressing problems facing capitalism are:

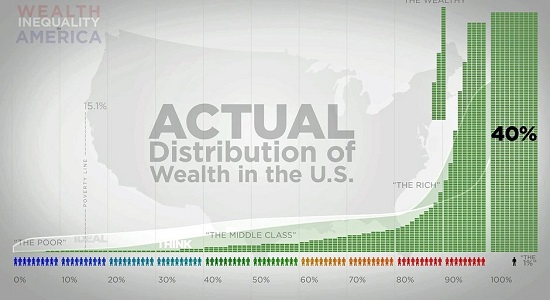

1) income inequality, the basis of Thomas Piketty’s bestseller Capital in the Twenty-First Century, and

2) the failure of laissez-faire markets to regulate their excesses, a common critique encapsulated by Paul Craig Roberts’ recent book The Failure of Laissez Faire Capitalism.

These critiques (and many similar diagnoses) reach a widely shared conclusion: capitalism must be reformed to save it from itself.

The proposed reforms align with each analyst’s basic ideological bent. Piketty’s solution to rising wealth inequality is the ultimate in statist centralization: a global wealth tax.

Roberts and others recommend reforming capitalism to embody social purpose and recognize environmental limits. Exactly how this economic reformation should be implemented is a question that sparks debates across the ideological spectrum, but the idea that capitalism can be reformed is generally accepted by left, right and libertarian alike.

Socio-economist Immanuel Wallerstein asks a larger question: can the current iteration of global capitalism be reformed, or is it poised to be replaced by some other arrangement?

Wallerstein and four colleagues explored this question in Does Capitalism Have a Future?(Oxford University Press, 2013).

Wallerstein is known as a proponent of world systems, the notion that each dominant economic-political arrangement eventually reaches its limits and is replaced by a new globally hegemonic system.

Wallerstein draws his basic definition of the current dominant system–let’s call it Global Capitalism 1.0–from his mentor, historian Fernand Braudel, who meticulously traced modern capitalism back to its developmental roots in the 15th century in an influential three-volume history, Civilization & Capitalism, 15th to 18th Centuries:

The Structures of Everyday Life: Volume 1

The Wheels of Commerce: Vol. 2

The Perspective of the World: Volume 3

From this perspective, there is a teleological path to global capitalism’s expansion beneath the market’s ceaseless cycle of boom-and-bust. This model of ever-larger systems of global dominance has been further developed by Braudel disciples such as Giovanni Arrighi (The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power and the Origins of Our Times).

It is this latest and most expansive iteration of capitalism–one dominated by the mobility of global capital, state enforcement of privately owned rentier/cartel arrangements and the primacy of financial capital over industrial capital–that Wallerstein and his collaborators view as endangered.

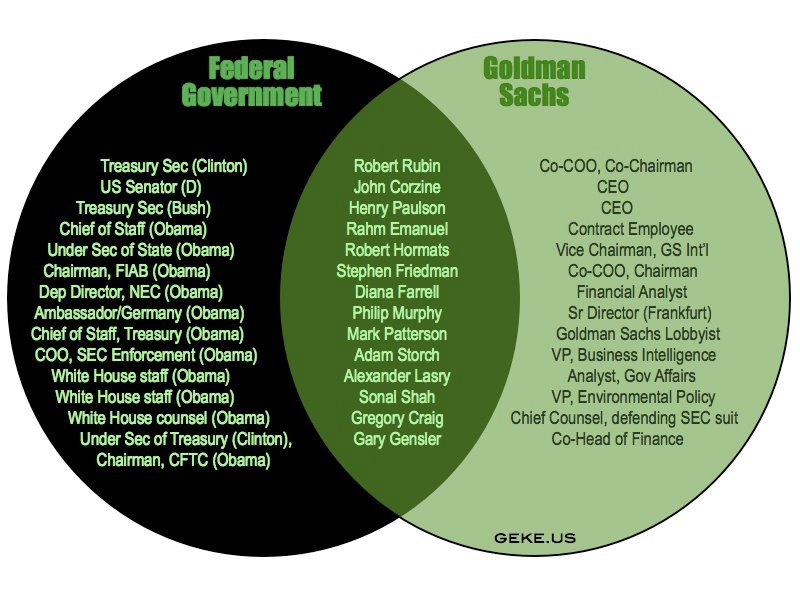

Amidst the conventional chatter of social spending countering markets gone wild–as if the only thing restraining rampant capitalism is the state–Wallerstein clearly identifies the state’s role as enforcer of private cartels.

This is not just a function of regulatory capture by monied elites: if the state fails to maintain monopolistic cartels, profit margins plummet and capital is unable to maintain its spending on investment and labor. Simply put, the economy tanks as profits, investment and growth all stagnate.

This is why Wallerstein characterizes this iteration of capitalism as “a particular historical configuration of markets and state structures where private economic gain by almost any means is the paramount goal and measure of success.”

Even those who reject this description of free markets and the self-interested pursuit of profit can agree that the prime directive of capitalism is the accumulation of capital: enterprises that fail to accumulate capital lose capital and eventually go bust.

As economist Joseph Schumpeter recognized, capitalism is not a steady-state system but one constantly reworked by “creative destruction,” the process of the less efficient being replaced by the more efficient.

In Wallerstein’s view, Global Capitalism 1.0 could end in the frustration of capitalists to continue reaping large and fairly secure profits. If capital can no longer accumulate capital, this iteration of capitalism runs out of oxygen and creative destruction will usher in a new arrangement. (Wallerstein’s chapter in the book is titledwhy capitalists may no longer find capitalism rewarding.)

Though the status quo believes that amending the political-financial rules is all that’s needed to maintain the current centralized arrangement, Wallerstein believes that following the old rules will actually intensify the coming structural crisis.

As the state-cartel crony-capitalism that dominates the financial and political realms unravels on multiple levels, it’s difficult not to agree with Wallerstein that the more the Status Quo pursues the same old Keynesian Cargo Cult script of central planning and free money for financiers, the more self-liquidating the system becomes.