Are Babies Dying in the Pacific Northwest Due to Fukushima? A Look at the Numbers

By Michael Moyer

Scientific American

A recent article on the Al Jazeera English web site cites a disturbing statistic: infant mortality in certain U.S. Northwest cities spiked by 35 percent in the weeks following the disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. The author writes that “physician Janette Sherman MD and epidemiologist Joseph Mangano published an essay shedding light on a 35 per cent spike in infant mortality in northwest cities that occurred after the Fukushima meltdown, and [sic] may well be the result of fallout from the stricken nuclear plant.” The implication is clear: Radioactive fallout from the plant is spreading across the Pacific in sufficient quantities to imperil the lives of children (and presumably the rest of us as well).

A recent article on the Al Jazeera English web site cites a disturbing statistic: infant mortality in certain U.S. Northwest cities spiked by 35 percent in the weeks following the disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. The author writes that “physician Janette Sherman MD and epidemiologist Joseph Mangano published an essay shedding light on a 35 per cent spike in infant mortality in northwest cities that occurred after the Fukushima meltdown, and [sic] may well be the result of fallout from the stricken nuclear plant.” The implication is clear: Radioactive fallout from the plant is spreading across the Pacific in sufficient quantities to imperil the lives of children (and presumably the rest of us as well).

The article doesn’t link to the Sherman/Mangano essay, but a quick search revealsthis piece that begins “U.S. babies are dying at an increased rate.” The authors churn through recently published data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to justify their claim that the mortality rate for infants in the Pacific Northwest has jumped since the crisis at Fukushima began on March 11. That data is publicly available, and a check reveals that the authors’ statistical claims are critically flawed—if not deliberate mistruths.

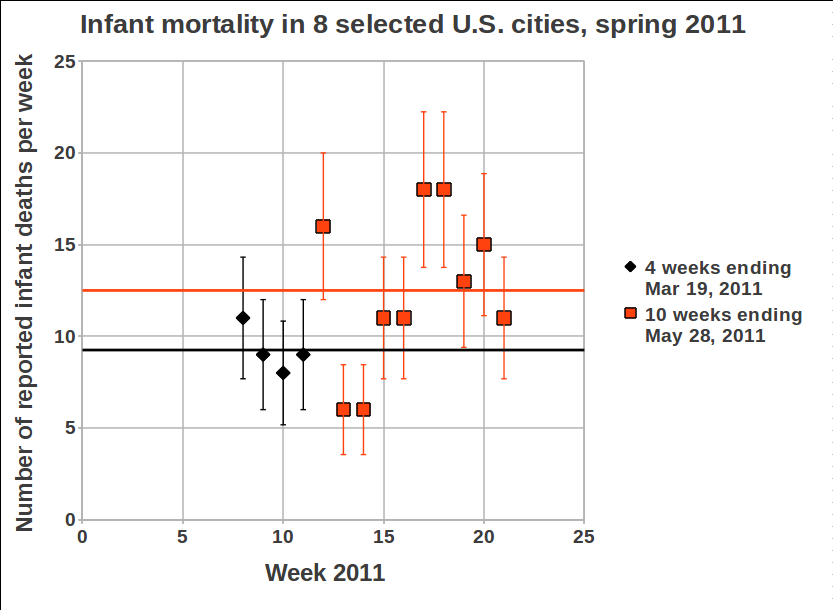

The authors gather their data from the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports. These reports include copious tables of data on death and disease in the U.S., broken down by disease (U.S. doctors reported 62 cases of rabies the week ending June 11) and location (30 of those were in West Virginia). Sherman and Mangano tally up all the deaths of babies under one year old in eight West Coast cities: Seattle; Portland, Ore.; Boise, Idaho; and the California cities of San Francisco, Sacramento, San Jose, Santa Cruz and Berkeley. They then compare the average number of deaths per week for the four weeks preceding the disaster with the 10 weeks following. The jump—from 9.25 to 12.5 deaths per week—is “statistically significant,” the authors report.

Let’s first consider the data that the authors left out of their analysis. It’s hard to understand why the authors stopped at these eight cities. Why include Boise but not Tacoma? Or Spokane? Both have about the same size population as Boise, they’re closer to Japan, and the CDC includes data from Tacoma and Spokane in the weekly reports.

More important, why did the authors choose to use only the four weeks preceding the Fukushima disaster? Here is where we begin to pick up a whiff of data fixing. Though the CDC doesn’t provide the data in its weekly reports in an easy-to-manipulate spreadsheet format (that would be too easy), it does provide a handy web interface that allows individuals to access HTML tables for specific cities. I copied and pasted the 2011 figures from the eight cities in question and culled all data aside from the mortality rates for children under one year old. You can see those numbers in a Google doc I’ve posted here. (Note: Because I use the most recent report, my mortality figures are slightly higher than the Sherman and Mangano’s, as some deaths aren’t reported to medical authorities until weeks afterward. The small difference doesn’t change the analysis.)

Better still, take a look at this plot that I’ve made of the data:

The Y-axis is the total number of infant deaths each week in the eight cities in question. While it certainly is true that there were fewer deaths in the four weeks leading up to Fukushima (in green) than there have been in the 10 weeks following (in red), the entire year has seen no overall trend. When I plotted a best-fit line to the data (in blue), Excel calculated a very slight decrease in the infant mortality rate. Only by explicitly excluding data from January and February were Sherman and Mangano able to froth up their specious statistical scaremongering.

This is not to say that the radiation from Fukushima is not dangerous (it is), nor that we shouldn’t closely monitor its potential to spread (we should). But picking only the data that suits your analysis isn’t science—it’s politics. Beware those who would confuse the latter with the former.