The Single Most Important Strategy Most Investors Ignore

Jeff Clark

Casey Research

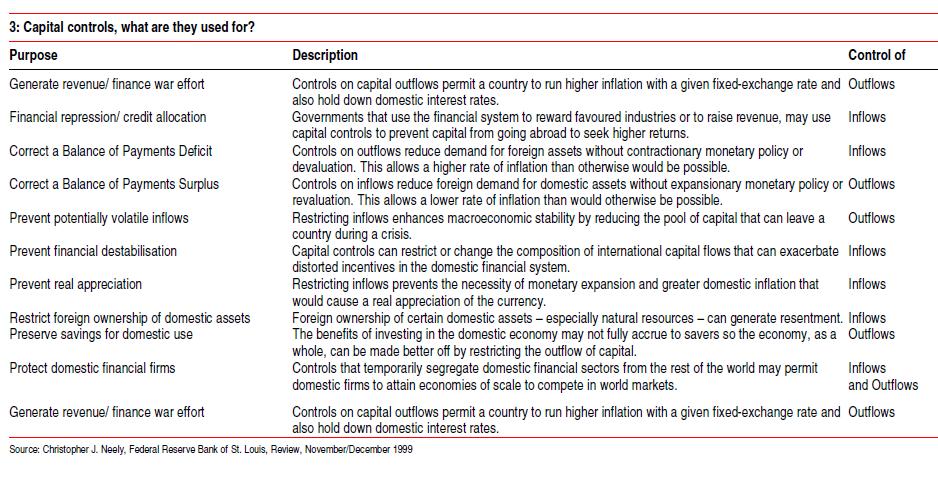

1: IMF Endorses Capital Controls

Bloomberg reported in December 2012 that the “IMF has endorsed the use of capital controls in certain circumstances.“

This is particularly important because the IMF, arguably an even more prominent institution since the global financial crisis started, has always had an official stance against capital controls. “In a reversal of its historic support for unrestricted flows of money across borders, the IMF said controls can be useful…”

Will individual governments jump on this bandwagon? “It will be tacitly endorsed by a lot of central banks,” says Boston University professor Kevin Gallagher. If so, it could be more than just your home government that will clamp down on storing assets elsewhere.

2: There Is Academic Support for Capital Controls

Many mainstream economists support capital controls. For example, famed Harvard Economists Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff wrote the following earlier this year:

Governments should consider taking a more eclectic range of economic measures than have been the norm over the past generation or two. The policies put in place so far, such as budgetary austerity, are little match for the size of the problem, and may make things worse. Instead, governments should take stronger action, much as rich economies did in past crises.

Aside from the dangerously foolish idea that reining in excessive government spending is a bad thing, Reinhart and Rogoff are saying that even more massive government intervention should be pursued. This opens the door to all kinds of dubious actions on the part of politicians, including—to my point today—capital controls.

“Ms. Reinhart and Mr. Rogoff suggest debt write-downs and ‘financial repression’, meaning the use of a combination of moderate inflation and constraints on the flow of capital to reduce debt burdens.”

The Reinhart and Rogoff report basically signals to politicians that it’s not only acceptable but desirable to reduce their debts by restricting the flow of capital across borders. Such action would keep funds locked inside countries where said politicians can plunder them as they see fit.

3: Confiscation of Savings on the Rise

“So, what’s the big deal?” Some might think. “I live here, work here, shop here, spend here, and invest here. I don’t really need funds outside my country anyway!”

Well, it’s self-evident that putting all of one’s eggs in any single basket, no matter how safe and sound that basket may seem, is risky—extremely risky in today’s financial climate.

In addition, when it comes to capital controls, storing a little gold outside one’s home jurisdiction can help avoid one major calamity, a danger that is growing virtually everywhere in the world: the outright confiscation of people’s savings.

The IMF, in a report entitled “Taxing Times,” published in October of 2013, on page 49, states:

“The sharp deterioration of the public finances in many countries has revived interest in a capital levy—a one-off tax on private wealth—as an exceptional measure to restore debt sustainability.”

The problem is debt. And now countries with higher debt levels are seeking to justify a tax on the wealth of private citizens.

So, to skeptics regarding the value of international diversification, I would ask: Does the country you live in have a lot of debt? Is it unsustainable?

If debt levels are dangerously high, the IMF says your politicians could repay it by taking some of your wealth.

The following quote sent shivers down my spine…

The appeal is that such a task, if implemented before avoidance is possible and there is a belief that is will never be repeated, does not distort behavior, and may be seen by some as fair. The conditions for success are strong, but also need to be weighed against the risks of the alternatives, which include repudiating public debt or inflating it away.

The IMF has made it clear that invoking a levy on your assets would have to be done before you have time to make other arrangements. There will be no advance notice. It will be fast, cold, and cruel.

Notice also that one option is to simply inflate debt away. Given the amount of indebtedness in much of the world, inflation will certainly be part of the “solution,” with or without outright confiscation of your savings. (So make sure you own enough gold, and avoid government bonds like the plague.)

Further, the IMF has already studied how much the tax would have to be:

The tax rates needed to bring down public debt to pre-crisis levels are sizable: reducing debt ratios to 2007 levels would require, for a sample of 15 euro area countries, a tax rate of about 10% on households with a positive net worth.

Note that the criterion is not billionaire status, nor millionaire, nor even “comfortably well off.” The tax would apply to anyone with a positive net worth. And the 10% wealth-grab would, of course, be on top of regular income taxes, sales taxes, property taxes, etc.

4: We Like Pension Funds

Unfortunately, it’s not just savings. Carmen Reinhart (again) and M. Belén Sbrancia made the following suggestions in a 2011 paper:

Historically, periods of high indebtedness have been associated with a rising incidence of default or restructuring of public and private debts. A subtle type of debt restructuring takes the form of ‘financial repression.’ Financial repression includes directed lending to government by captive domestic audiences (such as pension funds), explicit or implicit caps on interest rates, regulation of cross-border capital movements, and (generally) a tighter connection between government and banks.

Yes, your retirement account is now a “captive domestic audience.” Are you ready to “lend” it to the government? “Directed” means “compulsory” in the above statement, and you may not have a choice if “regulation of cross-border capital movements”—capital controls—are instituted.

5: The Eurozone Sanctions Money-Grabs

Germany’s Bundesbank weighed in on this subject last January:

“Countries about to go bankrupt should draw on the private wealth of their citizens through a one-off capital levy before asking other states for help.”

The context here is that of Germans not wanting to have to pay for the mistakes of Italians, Greeks, Cypriots, or whatnot. Fair enough, but the “capital levy” prescription is still a confiscation of funds from individuals’ banks or brokerage accounts.

Here’s another statement that sent shivers down my spine:

A capital levy corresponds to the principle of national responsibility, according to which tax payers are responsible for their government’s obligations before solidarity of other states is required.

The central bank of the strongest economy in the European Union has explicitly stated that you are responsible for your country’s fiscal obligations—and would be even if you voted against them! No matter how financially reckless politicians have been, it is your duty to meet your country’s financial needs.

This view effectively nullifies all objections. It’s a clear warning.

And it’s not just the Germans. On February 12, 2014, Reuters reported on an EU commission document that states:

The savings of the European Union’s 500 million citizens could be used to fund long-term investments to boost the economy and help plug the gap left by banks since the financial crisis.

Reuters reported that the Commission plans to request a draft law, “to mobilize more personal pension savings for long-term financing.”

EU officials are explicitly telling us that the pensions and savings of its citizens are fair game to meet the union’s financial needs. If you live in Europe, the writing is on the wall.

Actually, it’s already under way… Reuters recently reported that Spain has

…introduced a blanket taxation rate of .03% on all bank account deposits, in a move aimed at… generating revenues for the country’s cash-strapped autonomous communities.

The regulation, which could bring around 400 million euros ($546 million) to the state coffers based on total deposits worth 1.4 trillion euros, had been tipped as a possible sweetener for the regions days after tough deficit limits for this year and next were set by the central government.

Some may counter that since Spain has relatively low tax rates and the bail-in rate is small, this development is no big deal. I disagree: it establishes the principle, sets the precedent, and opens the door for other countries to pursue similar policies.

6: Canada Jumps on the Confiscation Bandwagon

You may recall this text from last year’s budget in Canada:

“The Government proposes to implement a bail-in regime for systemically important banks.”

A bail-in is what they call it when a government takes depositors’ money to plug a bank’s financial holes—just as was done in Cyprus last year.

This regime will be designed to ensure that, in the unlikely event a systemically important bank depletes its capital, the bank can be recapitalized and returned to viability through the very rapid conversion of certain bank liabilities into regulatory capital.

What’s a “bank liability”? Your deposits. How quickly could they do such a thing? They just told us: fast enough that you won’t have time to react.

By the way, the Canadian bail-in was approved on a national level just one week after the final decision was made for the Cyprus bail-in.

7: FATCA

Have you considered why the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act was passed into law? It was supposed to crack down on tax evaders and collect unpaid tax revenue. However, it’s estimated that it will only generate $8.7 billion over 10 years, which equates to 0.18% of the current budget deficit. And that’s based on rosy government projections.

FATCA was snuck into the HIRE Act of 2010, with little notice or discussion. Since the law will raise negligible revenue, I think something else must be going on here. If you ask me, it’s about control.

In my opinion, the goal of FATCA is to keep US savers trapped in US banks and in the US dollar, in case the US wants to implement a Cyprus-like bail-in. Given the debt load in the US and given statements made by government officials, this seems like a reasonable conclusion to draw.

This is why I think that the institution of capital controls is a “when” question, not an “if” one. The momentum is clearly gaining steam for some form of capital controls being instituted in the near future. If you don’t internationalize, you must accept the risk that your assets will be confiscated, taxed, regulated, and/or inflated away.

What to Expect Going Forward

- First, any announcement will probably not use the words “capital controls.” It will be couched positively, for the “greater good,” and words like “patriotic duty” will likely feature prominently in mainstream press and government press releases. If you try to transfer assets outside your country, you could be branded as a traitor or an enemy of the state, even among some in your own social circles.

- Controls will likely occur suddenly and with no warning. When did Cyprus implement their bail-in scheme? On a Friday night after banks were closed. By the way, prior to the bail-in, citizens were told the Cypriot banks had “government guarantees” and were “well-regulated.” Those assurances were nothing but a cruel joke when lightning-fast confiscation was enacted.

- Restrictions could last a long time. While many capital controls have been lifted in Cyprus, money transfers outside the country still require approval from the Central Bank—over a year after the bail-in.

- They’ll probably be retroactive. Actually, remove the word “probably.” Plenty of laws in response to prior financial crises have been enacted retroactively. Any new fiscal or monetary emergency would provide easy justification to do so again. If capital controls or savings confiscations were instituted later this year, for example, they would likely be retroactive to January 1. For those who have not yet taken action, it could already be too late.

- Social environment will be chaotic. If capital controls are instituted, it will be because we’re in some kind of economic crisis, which implies the social atmosphere will be rocky and perhaps even dangerous. We shouldn’t be surprised to see riots, as there would be great uncertainty and fear. That’s dangerous in its own right, but it’s also not the kind of environment in which to begin making arrangements.

- Ban vs. levy. Imposing capital controls is a risky move for a government to make; even the most reckless politicians understand this. That won’t stop them, but it could make them act more subtly. For instance, they might not impose actual bans on moving money across borders, but instead place a levy on doing so. Say, a 50% levy? That would “encourage” funds to remain inside a given country. Why not 100%? You could be permitted to transfer $10,000 outside the country—but if the fee for doing so is $10,000, few will do it. Such verbal games allow politicians to claim they have not enacted capital controls and yet achieve the same effect. There are plenty of historical examples of countries doing this very thing.

Keep in mind: Who will you complain to? If the government takes a portion of your assets, legally, who will you sue? You will have no recourse. And don’t expect anyone below your tax bracket to feel sorry for you.

No, once the door is closed, your wealth is trapped inside your country. It cannot move, escape, or flee. Capital controls allow politicians to do anything to your wealth they deem necessary.

Fortunately, you don’t have to be a target. Our Going Global report provides all the vital information you need to build a personal financial base outside your home country. It covers gold ownership and storage options, foreign bank accounts, currency diversification, foreign annuities, reporting requirements, and much more. It’s a complete A to Z guide on how to diversify internationally.