$450 Million Da Vinci Painting A Fake? Global Art Market Is Just Another Massive Multi-Decade Fraud

Global Art Market: Mother Of All Bubbles

Largest Art Market Transactions Are Conducted With Utmost Secrecy For Very ‘Good’ Reason

by Art Historians For Fair Markets

Very few understand the inner workings of the global art market. Those few who do understand it are insiders who push the buttons and pull the levers behind the curtain.

The institutional arrangements which comprise the world’s high-end art marketplace have been fastidiously put into place over many centuries. This is the playground of the ultra-rich and powerful, well-connected and corporate cronies.

Therefore, one is compelled to ask: Why would extremely wise and knowledgeable investors purchase fantastically overpriced paintings just before the art market bubble is ready to pop?

The recent buying (and selling) spree of high-end artwork makes absolutely no sense at all, unless the market is completely rigged … just like the stock market … the commodities market, the currency markets, the derivatives market, etc., etc, etc.

Long before there were any of these other financial instrument exchanges there was art, perhaps one of the oldest means of exchange. Consequently, the art market has been around so long that it is quite easy for those who control it to manipulate it ANY WAY THEY WANT TO.

There are two HUGE factors which have undermined the Art Market over many decades.

#1 There are now countless numbers of fake and fabricated pieces of high-end art work in the marketplace.

#2 The real prices actually paid, for the most exorbitantly priced pieces of art, cannot be substantiated because of strict confidentiality clauses and rules.

These two ongoing market dynamics have served to cordon off the entire high-end art market from all but a few billionaires and institutional investors. However, even in these cases, the buyer must rely on the expertise and integrity of those very experts who can legitimately authenticate a nearly 300 million dollar Gauguin painting. Just how many art authorities are there in the world who can competently identify an original painting from a 19th century impressionist or old world master?

Especially in a technologically sophisticated environment is it becoming more and more difficult to spot the fakes. Counterfeit paintings, manufactured sculptures and the like have always been around, except that now there are many more of them, and they are much higher quality. Some of the bogus art is even more convincing than the originals!

As for point #2, all of the highest priced art transactions are conducted with the utmost secrecy — for quite obvious reasons — and, therefore, cannot be corroborated. Many of the largest transactions have clauses of the strictest confidentiality built into the sales contract, which effectively eliminate the possibility of tracking down the legitimacy of the purchase. Some have even surmised that some of these hundred million dollar transactions have not even taken place and that they are nothing but a sham conducted to artificially manipulate art prices upwards … as in “through the proverbial roof”.

When one considers exactly what pieces have been sold over the past few years for prices that are as inconceivable as that are preposterous, the prevailing climate begs for further investigation.

After all, who in their right mind would pay such astronomical prices for pieces of decaying artwork which cost tremendous amounts to adequately insure, properly house, safely transport and correctly maintain?

Biggest Auction Houses: Classic Example Of the Fox Guarding The Hen House

Let’s face it, just like the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), both Sotheby’s and Christie’s function as the clearing house (and brokerage firm) for a vast majority of the world’s highest priced art transactions. The very fact that they can serve in both capacities — clearing house and brokerage firm — at the same time, creates ample opportunity for the fox to take advantage of the hen house. In each case these auction houses, of ‘sterling’ repute, (hmm, sounds like the British pound) are completely owned and operated by the same characters who have a substantial interest in fixing the game.

What game?

When a Gauguin sells for almost $300 million, it permits every art dealer and art gallery owner in the world to blow that horn. In this way, not only is every Paul Gauguin painting immediately inflated (many say artificially) in price, so are all the impressionist paintings of the last two centuries.

One can see very easily how this game really works — on raw emotion and fictitious sales hype, and with no validation of the largest transactions which occur in an effectively clandestine ‘marketplace’. That’s because there really is no marketplace; just a group of privileged insiders exchanging their artwork for prices real or imagine or otherwise, since no one can substantiate them … ever.

Now take a good look a these prices for the TOP TEN most expensive paintings ever sold publicly.

What savvy art investor or whimsical billionaire would ever pay such prices for an old artifact with forever-fading oil colors or water colors on canvas?

Particularly in the case of the more modern artists do these obviously unwarranted prices make NO sense at all; unless, of course, they were meant to rev up the marketplace. It really only takes one or two outrageous sales to completely skew the pricing for an entire segment of the art market.

That two Pablo Picasso paintings would command the number 3 and 7 spots for $179.4 million and $157.5 million, respectively, is particularly suspect. In view of how easy it is to duplicate Picasso’s art, any buyer of his work is really taking a gamble — a HUGE gamble, not too unlike those who are buying way overpriced stocks on the NYSE throughout 2015.

How do you spell S U C K E R ‘S R A L L Y?

Afterthought:

Who would ever really pay $179.4 million for Pablo Picasso’s “The Women of Algiers”? This is nothing more than an old man painting his favorite female body parts … over and over again, while looking through a Coke bottle. Truly, those who would pay such a ridiculous sum for the inferior painting below are as crazy as the old codger who painted it.

___

https://themillenniumreport.com/2015/05/the-global-art-market-mother-of-all-bubbles/

TMR Update:

The following story was just published by Bloomgerg.com and dovetails nicely with our previous exposé posted above.

The Millennium Report

November 17, 2017

Why Are Critics Calling the $450 Million Painting Fake?

The art world and chattering classes are casting doubt on a recently sold Leonardo Da Vinci. Experts say it’s real.

By James Tarmy

Bloomberg Pursuits

Even before Leonardo Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi went to auction last night at Christie’s in New York, naysayers from around the art world were savaging its authenticity. Various advisors were muttering darkly, both online and in the auction previews, and one day before the sale New York magazine’s Jerry Saltz wrote that though he’s “no art historian or any kind of expert in old masters,” just “one look at this painting tells me it’s no Leonardo.”

And that was before the painting obliterated every previous auction record, selling, with premium, for $450 million.

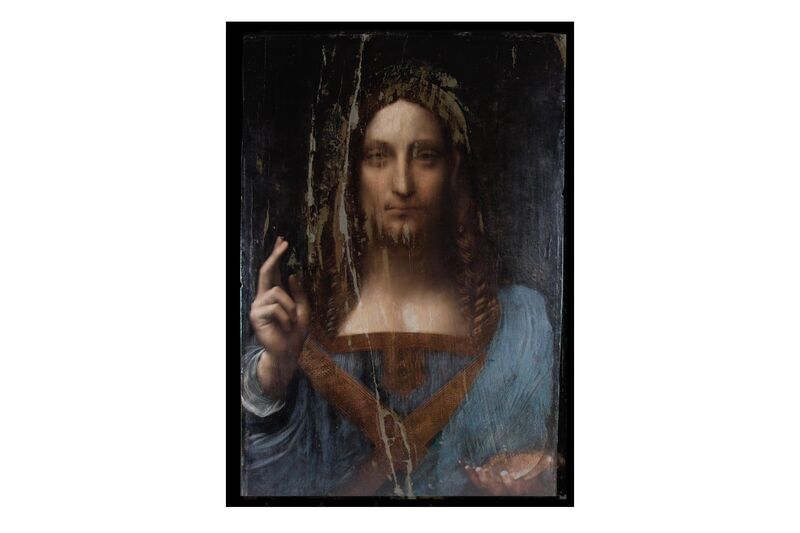

Leonardo Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, which sold at Christie’s on Wednesday for $450 million. Source: Christie’s

Shortly after the gavel came down on Wednesday evening, the New York Times published a piece by the critic Jason Farago where, after also noting that he’s “not the man to affirm or reject its attribution,” declared that the painting is “a proficient but not especially distinguished religious picture from turn-of-the-16th-century Lombardy, put through a wringer of restorations.”

Had the buyer of the most expensive painting in the world just purchased a piece of junk?

“All of the most relevant people believe it’s by Leonardo, so the rather extensive criticism that goes ‘I don’t know anything about old masters, but I don’t think it’s by Leonardo’ shouldn’t ever have gone to print,” says the British old masters dealer Charles Beddington. “Yes, it’s a picture that needed to be extensively restored. But the fact that it’s unanimously accepted as a Leonardo shows it’s in good enough condition that there weren’t questions of authenticity.”

After speaking to multiple prominent old masters dealers— a group not exactly known for holding its tongue— the real issue regarding the Leonardo’s validity seems to be a question of education: “All old masters have had work done to them,” says the dealer Rafael Valls, whose London gallery is directly across from Christie’s.

“They’ve all been scrubbed and cleaned, but when you think about a particular painting and say, ‘oh it’s by Titian, but a quarter of it was recreated by other restorers,’ it still is what it is.”

A detail of the painting. Source: Christie’s

Those in the art world who dismiss its authenticity, dealers say, are simply transferring criteria used to judge contemporary art onto old masters—the equivalent of comparing the specs of a new Honda against a Ferrari from 1965. They’re both cars, but that’s where the similarities end.

“To a certain extent you have to put condition aside,” says the dealer Johnny van Haeften. “Of course it’s not perfect, and of course it’s not mint. But can you get another one?”

The Backstory

The painting was probably done in 1500, and by the 1600s it had made it into the court of Charles I, after which it popped up intermittently in inventory records, disappearing in the 1700s and then reappearing in 1900, when it was counted among the inventory of a manor house in Richmond. It was then sold in 1958 and disappeared yet again, only to resurface at auction in 2005, when three old masters dealers picked it up for $10,000.

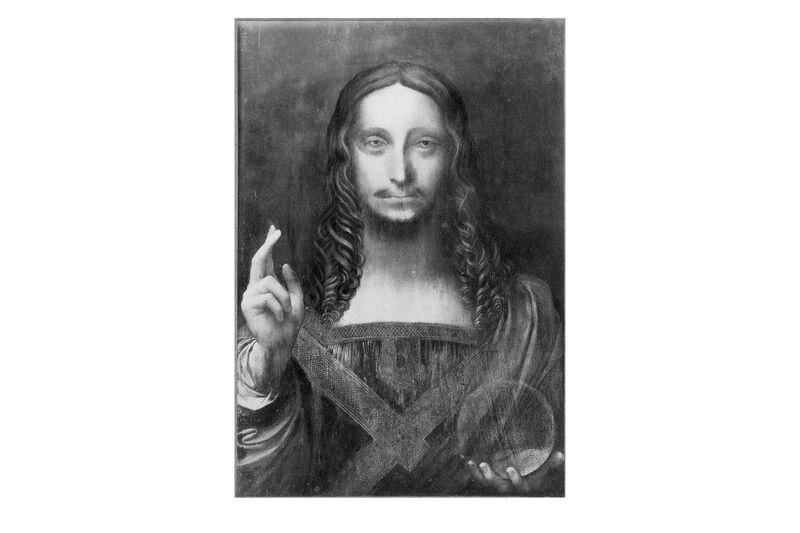

A black-and-white photograph of the painting as it existed in 1904. Source: Christie’s

A black-and-white photograph of the painting as it existed in 1904. Source: Christie’sThe dealers hired the noted restorer Dianne Dwyer Modestini (previously of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art) to remove much of the filth and varnish, at which point the painting was effectively a shell of its former self, and significant portions of the composition were missing altogether.

“I’ve seen the picture stripped,” says Van Haeften, who is friends with one of the work’s previous owners. “There are damages to the panel, and it has certainly had a checkered career.”

Bruised and Battered

The Leonardo could have been damaged in any number of ways. First, there’s transportation to consider—it had to make its way from Leonardo’s studio to England on horseback, or in a cart, and then by boat. Then consider the conditions of wherever it hung for the next several centuries: There could have been a leaky roof, a moldy room, or a smoky candelabra nearby.

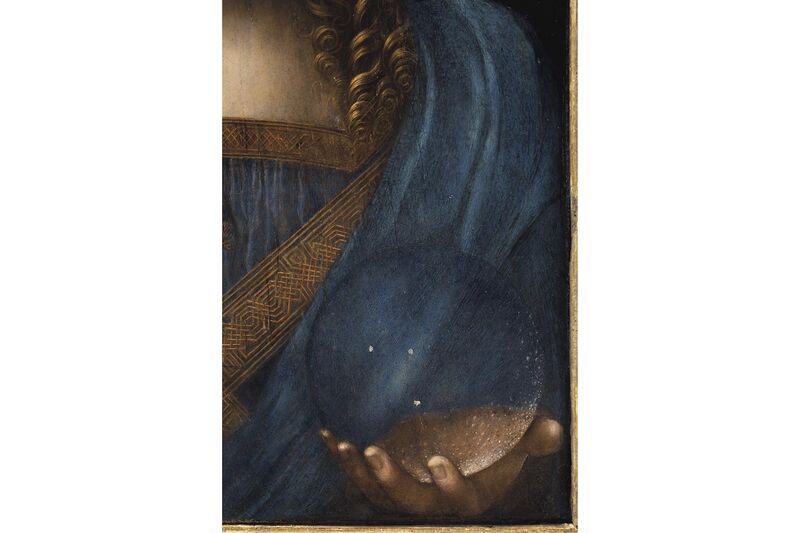

A screenshot of a video released by Christie’s that transitioned from an infrared scan of the painting to the restored work. Source: Christie’s

Of course, people even in the 18th century were aware that their paintings got filthy, and so “normally, every time paintings changed hands,” Beddington, the dealer says, “they got cleaned quite harshly.” The Leonardo, he says, “obviously changed hands quite a bit.”

Every time a painting was scrubbed, “when you cleaned something like that orb, which is delicately painted, you end up taking something away from it,” Beddington continues. “And that’s normal.”

When Modestini restored the painting, therefore, it was expected that she would paint in what had been lost—both by her cleaning and by cleanings of previous owners—in a way that was “keeping in character with what is left,” Beddington says.

A Question of Degrees

The question for most old masters buyers then, is not whether a painting is “authentic,” but to what degree it’s original. “For the vast majority of old masters, condition is of enormous importance,” says Van Haeften.

Many old masters have only minimal damage or restoration—“an awful lot of Canalettos are in a near-perfect state,” says the dealer Simon Dickinson—but when it comes to infinitely rarer artworks, “maybe in the case of a Michelangelo, Raphael, and Vermeer, you have to compromise on the condition,” van Haeften says. “Because there’s no other possibility of acquiring one.”

“The market tolerance for a Da Vinci is quite different than the tolerance for a Van Gogh, say,” said Brooke Lampley, Sotheby’s incoming fine art division chairman, in an interview on Bloomberg Surveillance. “Because even though a Van Gogh is scarce and someone will pay $81 million for a great one, there are still more to be had than Da Vinci, for whom there are fewer than 20 paintings in the world. People have a much higher threshold for what over-painting or condition problems there could be in a painting.”

It was only natural, therefore, that the Leonardo buyer would be willing to compromise on this more than others; they weren’t going to find a better one.

Another detail of the painting. Source: Christie’s

But the buyer didn’t quite compromise as much as critics would like to believe. The two central critiques, namely that it’s too stiff, and that it doesn’t look like the Mona Lisa, “are ridiculous,” Beddington says. “The composition of Christ the Redeemer is always a stiff composition.” The fact that it bears little resemblance to the Mona Lisa, he continues, “is that it’s a completely different type of painting.”

More Than the Painting

The dynamism of the composition, however, is only part of the painting’s value. “You’re buying much more than the painting, you’re buying its history,” says Dickinson. “Who’s looked at it, who’s touched it: You’re selling a dream, that what you’re in front of, Leonardo was once in front of.”

The work, therefore, is as much an artifact as it is a painting, its reputation and its history just as talismanic a pull as its actual composition. (Similarly, people don’t crowd the Mona Lisa in the Louvre every day just because they’re devotees of art history.)

“You have to accept it’s more an object than a work of art in a perfect state,” says Van Haeften.