The crew of the Russian frigate Osliaba during the American Civil War in Alexandria, Virginia, 1863. The Civil War saw both the Union and the Confederacy diplomatically attempt to find allies in Europe, with the Union gaining an ally in Czarist Russia, which sent two fleets in the autumn of 1863. (Photo by Archive Photos/Getty Images)

American Civil War: When Russia Blocked British-led Intervention against the Union

When the Rothschild’s lost the American Revolution they blamed the Russian Czar and the Russians for assisting the Colonists by blockading British Ships.

On one side was the Union and the Russian Empire under Alexanders I and II, and on the other the Confederacy in alliance with England and France- Louis Napoleon (III).

The cornerstone of Britain’s operational policy, from no later than 1860 on, was to dismember both the United States and Russia. This was the prelude to enacting a “new world order,” devoid of sovereign nation states, an order centered on a British-controlled Grand Confederacy, labelled by British policymakers “The United States of Europe.”

By Konstantin George

It was during the Lincoln administration, when a wartime alliance between the United States and Russia was negotiated by U.S. Ambassador to Russia Cassius Clay (1861-1862 and 1863-1869). It was Russia’s military weight and threats of reprisals against Britain and France, that prevented any British-led intervention against the Union.

Two opposing alliances

The Union’s survival and ultimate victory was achieved in part thanks to the influential “American” faction in Russia, to whose outlook Alexander II tended. This faction stuck to its guns, despite all British threats, to ensure the survival and development of the United States for the common interest of Russia and America.

Russia’s huge land armies were ready to roll over the Ottoman Empire and India, thus ending British political domination of an area extending in a great arc from the Balkans through the Middle East to London’s sub-continental “jewel” of India.

The cornerstone of Britain’s operational policy, from no later than 1860 on, was to dismember both the United States and Russia. This was the prelude to enacting a “new world order,” devoid of sovereign nation states, an order centered on a British-controlled Grand Confederacy, labelled by British policymakers “The United States of Europe.”

A history of collaboration

What was achieved during the Civil War by the two “superpowers” was the consummation of a quarter-century-long bitter struggle by factions in the United States and Russian against the London-orchestrated political machines in their respective nations. From 1844 to 1860, British agents of influence repeatedly sabotaged earlier potentialities for the alliance to develop. It was a quarter-century punctuated with missed opportunities and tough lessons learned, as a result of which the strategic perceptions and capacities for action of the foremost of the U.S. Whigs and their Russian counterparts were shaped and increasingly perfected.

The foundation of U.S.-Russian collaboration was laid in the 1763-1815 period. It was the product of the political influence exerted within Russia by the networks organized by Benjamin Franklin in the Russian Academy of Science (whose leading members were followers of the tradition of technological progress established by the collaboration of Gottfried Leibniz and Peter the Great) and through the American Philosophical Society.

In the period from 1776 to 1815, Russia twice played a crucial role in safeguarding the existence of America. During the Revolutionary War, the acceptance of Epinus’ draft of a Treaty of Armed Neutrality by Russian Premier Count Panin was not only key in thwarting Britain’s plans for building an anti-American coalition in Europe, but also marked a signal triumph by the Russian friends of Benjamin Franklin, in wresting political hegemony away from the pro-British Prince Potemkin. In the War or 1812, Russia, under Czar Alexander I, submitted a near-ultimatum to England to hastily conclude an honourable peace with the United States and abandon all English claims of territorial aggrandizement. The American negotiators were the first to confirm that only the application of Russian pressure produced the sudden volte-face in Britain’s attitude that achieved the Treaty of Ghent.

One may also note that directly prior to the War of 1812, through the negotiating efforts of John Quincy Adams (at the time United States Minister to Russia), exponential growth rates in U.S.-Russian trade were achieved. By 1911, the United States had by far and away become Russia’s largest trading partner.

The event that completed the molding and toughening of the commitment to entente of the Russian and American factions was the 1853-56 Crimean War. Russia’s humiliation, and the acute realization that British policy was orienting toward actual dismemberment of the Russian Empire, together with the accrued lessons of the missed opportunities of the 1844-46 period, burned in the requisite lessons. The fundamental point that could no longer be ignored was that Russia would have no security as a nation, let alone prosperity, unless it committed itself to the abolition of serfdom and a policy of industrialization to fortify itself against the British monarchy.

To most Americans today, the image of the Crimean War connotes a war waged by “civilized” England and France against “semi-barbarous” Russia, with the clearest image being the romantic drivel of Tennyson’s “Charge of the Light Brigade.” In 1854, most of the American population was avowedly pro-Russian in its attitude toward that conflict. The Whig press, led by the New York Herald, was openly advocating a U.S.-Russian alliance, in response to Russia’s repeated requests for assistance.

The United States Minister to St. Petersburg, T.H. Seymour, in a line of argument that illustrates the Whig thinking at the time, repeatedly warned the foolish President Franklin Pierce and his Anglophile Secretary of State William Marcy, what Britain was up to. He wrote to Marcy, in a letter dated April 13, 1854:

“the danger is that the Western powers of Europe … after they have humbled the Czar, will domineer the rest of Europe, and thus have the leisure to turn their attention to American affairs.”

Under the rotten Pierce and Buchanan administrations, alliance was out of the question, but the process that was to define the Grand Design was developed in the years 1855 to 1861.

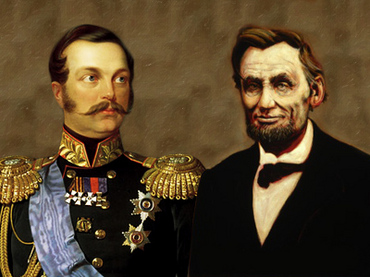

Cszar Alexander II (1818-1881). Tsar of all the Russias from 1855 to 1881

Cszar Alexander II (1818-1881). Tsar of all the Russias from 1855 to 1881

On the eve of the Civil War

During those years, the Russian “American faction” led by the new czar, Alexander II, Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov, and a group in the Russian Navy Ministry under the Grand Duke Constantine (which included the minister of war, Count Dmitri Miliutin, and the minister of finance, Mikhail Reutern), battled the feudal provincial nobility, which formed the social backbone of the “British faction” within Russia. Gorchakov, the central figure in determining the American faction’s policy moves, was not overly concerned, during this period, that the United States government, under the wretch Buchanan, would ignore and reject Russia’s offers of cooperation. His goal was much more sophisticated: to gain the acceptance of the American Whig grouping of the entente foreign policy perspective. This goal was achieved.

Thus, from 1855 on, Russia renewed as a standing offer the donation of Alaska to the United States, under the anti-British Empire conditions enunciated first in 1845. This standing offer was followed up with numerous substantial project offers to American capitalists.

Most notable were the Russian government’s Siberian-Far East and Near East development packages. In 1858, Russia proposed an agreement with the United States for cooperation in developing trade with China. In conjunction with this offer, Russia unilaterally opened the entire Amur River basin region (the maritime Provinces of Siberia) to free trade with the United States. The series of development proposals had begun as early as June 18, 1855, when Russia offered to extend its facilities to the United States in negotiating a commercial treaty with Persia, a step that would have begun the process of ending British hegemony in the region. During the 1858-60 period, United States ambassador to Russia Francis Pickens wrote on numerous occasions urging U.S.-Russian joint trade and economic expansion to effect a strategic shift against England.

On Jan. 12, 1859, Pickens wrote:

“Russia can hold a more certain control over Europe by her influence in the East, and she wishes the U.S. to tap the China trade from the East in order to keep England out.”

On April 17, 1860, after talks with officials of the Russian Foreign Ministry, Pickens conveyed an urgent warning to Washington that a full U.S.-British rupture was close, concluding with this advice:

“It is thus imperative that we keep an able Minister here … to produce through Russia a strong organization of the Baltic States against the power of England.”

This letter is of extraordinary historical significance, as it testifies directly that the relevant factions in the United States and Russia were convinced–correctly–that danger of a British-inspired conflict against the United States was rapidly increasing. Pickens’s policy, reflecting the views of Alexander II and Gorchakov, was geared to imminent or actual war conditions, conditions of acute danger to the survival of the American republic. The Russian government had arrived at precisely such an evaluation in the spring of 1860, and, under Gorchakov’s direct personal supervision, dispatched a top-level covert intelligence mission to the United States, headed by Col. Charles DeArnaud. That team was to play a decisive role in stymieing the Confederacy’s 1861 blitzkrieg strategy.

With the advent of the Lincoln administration, the U.S.-British rupture came to a head. All the Russian economic development proposals of the preceding five years were ripe for implementation. American Whigs, led by Lincoln, Clay, Admiral Farragut, and others, were preparing to launch a policy to develop Russia industrially and militarily.

In the Western Hemisphere, the end of British control over Ibero-America and Canada was considered imminent. The deputy foreign minister of Colombia expressed this sentiment:

“The United States Civil War is a step in the direction of the United States’ mission, to regenerate the whole continent, and … the United States and Russia, the two great Northern powers, `Colossi of two continents,’ if they could identify their interests, would be the surest bulwark of the independence of the world.”

Canada was all but ready to be annexed by the United States in 1861. By 1860, the United States government was receiving a tidal wave of petitions from western Canada urging annexation to the United States. Similar agitation was widespread in Lower Canada (Quebec). The Nor Wester, a newspaper in the Red River settlement that serviced the western region, wrote in an editorial, “England’s policies leave us no choice but to break.”

This, then, was the strategic conjuncture in 1860, when Britain utilized the last portion of the traitor Buchanan’s term in office to launch its project for Southern secession.

Ambassador Clay and Lincoln’s policy

President Lincoln’s top priority in foreign policy following Fort Sumter was forging a strategic alliance with Russia. Lincoln was aware that under the political hegemony of Foreign Minister Gorchakov, Russia was modernizing. The freeing of the serfs had occurred in the spring of 1861, and a vast program of railroad building was under way. Lincoln was also aware that both Gorchakov and the czar were pro-American and anti-British.

In May 1861, in choosing his personal envoy to St. Petersburg, Lincoln went outside all normal channels, and selected the nephew of American Whig statesman Henry Clay, Cassius Marcellus Clay, as his ambassador to Russia.

Clay viewed his primary task as developing and consolidating the Russian elite into an unbeatable political machine, such that it would acquire the talent and muscle necessary to see through Russia’s full-scale industrialization. Clay brought with him many copies of one of the primary treatises of the “American System” of political economy, Henry Carey’s book The Harmony of Interests: Agricultural, Manufacturing, and Commercial, hand-delivering them to Alexander II, Gorchakov, Navy Minister Prince Dolgoruky, Grand Duke Constantine, and a host of other high officials and industrialists. Clay toured the major cities, delivering speeches to thunderous applause from captains of industry, regional and national government officials, and merchants, expounding on the need for Russia to industrialize. His speeches were reprinted throughout the Russian press, and the name Henry Carey became a household word in Russia.

In his memoirs, Clay described the effect of his industrialization drive in Russia:

“A large class of manufacturers was aggregated about Moscow…. England was our worst enemy in the world and I sought out how I might most injure her. Russia with her immense lands and resources, and great population, was a fine field for British manufactures, and she had made the most of it. I procured the works of H.C. Carey of Philadelphia, and presented them to the Foreign Office, to the Emperor himself. So, it began to be understood that I was the friend of home industry–the `Russian System.’ I encouraged the introduction of American arms, sewing machines, and all that, as far as I could; the mining of petroleum, and its manufacture; and got the United States to form a treaty preventing the violation of trademarks in the commerce of the two nations. So, when I was invited to Moscow, it was intimated that a tariff speech would be quite acceptable. A dinner was given me by the corporate powers of Moscow….

They got up a magnificent dinner; and with the American and Russian flags over my head, I made a regular tariff speech. It was translated into Russian as I spoke, and received immense applause. It was also put in Russian newspapers and into pamphlet form, circulated in the thousands all over the Empire. This touched England in the tenderest spot; and whilst Sir A. Buchanan and lady [the British ambassador, who was present] was too well bred to speak of it, one of the attachés was less discreet and shouted how much I threatened British trade. The dinner was photographed at the time.

“I found that the argument which I had made for years in the South, in favour of free labour and manufactures, as cofactors, was well understood in Russia; and since emancipation and education have taken a new projectile force, railroads and manufactures have the same propulsion as is now exhibited in the `Solid South.’|”

Clay’s speech concluded with the Russian industrialists toasting the “great American economist Henry Carey.”

Clay also went to work paving the way for the military alliance that would dismantle the British Empire, and in conjunction with this, negotiated with Russia the construction of a Washington-St. Petersburg cable, via the Pacific through San Francisco and Vladivostok. Here is how he motivated the cable project:

“If we have to battle England on the sea, and should Russia be our ally, we shall have means of much earlier intelligence than she…. I think ourselves fortunate in having this great power as our sincere friend. We should keep up this friendly feeling, which will finally give us an immense market for our commerce, and give us a most powerful ally in common danger. We will and must take a common interest in the affairs of Europe.”

After the war, Clay summarized his mission as follows:

“I did more than any man to overthrow slavery. I carried Russia with us and thus prevented what would have been a strong alliance of France, England, and Spain against us, and thus saved the nation.”

The entente concept of Clay and Lincoln was developed in full, in a Clay dispatch to Lincoln from St. Petersburg, dated July 25, 1861:

“I saw at a glance where the feeling of England was. They hoped for our ruin. They are jealous of our power. They care neither for the North nor the South. They hate both. The London Times … in concluding its comments on your message [Lincoln’s July 5, 1861 message to Congress] says: `And when we prefer a frank recognition of Southern independence by the North to the policy avowed in the President’s message, it is solely because we foresee as bystanders that this is the issue in which after infinite loss and humiliation the contest must result.’ And that is the tone of England everywhere…. If England would not favor us whilst following the lead of the anti-slavery policy–she will never be our friend. She will now, if disaster comes upon our arms, join our enemies. Be on your guard….

“All the Russian journals are for us. In Russia we have a friend. The time is coming when she will be a powerful one for us. The emancipation [of the serfs] move is the beginning of a new era and new strength. She has immense lands, fertile and undeveloped in the Amoor country, with iron and other minerals. Here is where she must make the centre of her power against England. Joined with our Navy on the Pacific coast we will one day drive her [England] from the Indies: The source of her power: and losing which she will fall.”

The communication concluded with advice to Lincoln to:

“extend the blockade to every possible point of entry, so that if England does intervene–she will be the aggressor before all the world. Don’t trust her in anything.”

From the Russian court

In this earliest phase of the developing entente, the Russians were pro-American, though cautious. The caution was a lawful expression of a legitimate Russian concern: The Russians demanded to know if Lincoln would stand firm and fight the conflict through to preserve the Union. This was precisely the line of questioning of the czar’s first meeting with Clay in July 1861, culminating with the question of what the Union would do should England intervene. Clay advised Lincoln:

“I told the Emperor we did not care what England did, that her interference would tend to unite us the more.”

After this U.S. reassurance, Russia stood firmly behind its U.S. alliance. The policy was elaborated in a lengthy personal communication from Russian Foreign Minister Gorchakov to President Lincoln, dated July 10, 1861:

“From the beginning of the conflict which divides the United States of America, you have been desired to make known to the federal government the deep interest with which our August Master [Czar Alexander II] has been observing the development of a crisis which puts in question the prosperity and even the existence of the Union.

“The Emperor profoundly regrets that the hope of a peaceful solution is not realized and that American citizens, already in arms against each other, are ready to let loose upon their country the most formidable of the scourges of political society–civil war.

“For the more than eighty years that it has existed the American Union owes its independence, its towering rise, and its progress, to the concord of its members, consecrated, under the auspices of its illustrious founders, by institutions which have been able to reconcile union with liberty. This union has been fruitful. It has exhibited to the world the spectacle of a prosperity without example in the annals of history….

“The struggle which unhappily has just arisen can neither be indefinitely prolonged, nor lead to the total destruction of one of the parties. Sooner or later it will be necessary to come to some settlement, which may enable the divergent interests now actually in conflict to coexist.

“The American nation would then give proof of high political wisdom in seeking in common such a settlement before a useless effusion of blood, a barren squandering of strength and of public riches, and acts of violence and reciprocal reprisals shall have come to deepen an abyss between the two parties, to end in their mutual exhaustion, and in the ruin, perhaps irreparable, of their commercial and political power.

“Our August Master cannot resign himself to such deplorable anticipations … as a sovereign animated by the most friendly sentiments toward the American Union. This union is not simply in our eyes an element essential to the universal political equilibrium. It constitutes, besides, a nation to which our August Master and all Russia have pledged the most friendly interest; for the two countries, placed at the two extremities of the world, both in the ascending period of their development appear called to a natural community of interests and of sympathies, of which they have given mutual proofs to each other….

“In every event the American nation may count on the part of our August Master during the serious crisis which it is passing through at present.”

Lincoln was deeply moved on receipt of this Russian policy statement, telling the Russian ambassador:

“Please inform the Emperor of our gratitude and assure His Majesty that the whole nation appreciates this new manifestation of friendship. Of all the communications we have received from the European governments, this is the most loyal.”

Lincoln then requested permission, which was granted, to give the widest possible publicity to the Russian message. This was crucial. The U.S.-Russian alliance was no secret pact. Quite the contrary, by mutual agreement between the two nations, the arrangement was given as much publicity as possible, as were the reasons behind it and its absolute necessity to the Union. Only later was the historic entente sold by Anglophile historians as a Russian move for “balance” on the European continent.

At the point of maximum war danger between Great Britain and the United States, the London satirical publication Punch published a vicious caricature of US President Abraham Lincoln and Russian Tsar Alexander II, demonizing the two friends as bloody oppressors. From Punch, October 24, 1863

Sabotage efforts by a `fifth column’

Clay’s success in consolidating the Union-Russian alliance produced more than a mild panic in London, and the British fifth column in the U.S. government began to lobby Lincoln for Clay’s recall and replacement. The removal of Simon Cameron as secretary of war, on the grounds of rank incompetence, was to become the object of a “double judo” by the British agents of influence.

In the spring of 1862, Lincoln was persuaded by William Seward and his allies to replace Cameron with the traitor Edwin Stanton as secretary of war, while Cameron was shunted off to become the new U.S. ambassador to Russia, replacing Clay. Clay was bitter over the move, and begged Lincoln to allow his nephew, who had accompanied him as his assistant, to succeed him. Despite these protests, Clay was recalled, leaving St. Petersburg in June 1862, the same month in which Cameron arrived.

Clay fought these dirty manoeuvres tooth and nail, pointing out to Lincoln that the purpose of appointing Cameron to St. Petersburg was to ensure no effective American presence and communication with the Russian government during the most critical phase of the Civil War. Clay wrote to Lincoln in June 1862:

“I had made arrangements to stay here and made the necessary expenditures accordingly. I have several thousands of roubles of property here, which is usually turned over to successors–but Mr. Cameron cannot buy: He says he will positively ask leave to retire from this post at the end of the next quarter, the 1st of September next. He proposes to come home on your leave of absence, and then remain.”

This letter makes clear how transparent the traitors’ maneuver was: Get Clay out, put in Cameron as a rump, three-month ambassador in name only, and then leave the U.S.-Russian entente severed during precisely the phase of Civil War in which the danger of overt British military intervention was greatest.

Two things were to deny the British-agent conspirators the fruit of these evil schemes. Clay, though losing the recall battle, was to return in short stead to St. Petersburg, as we shall see; and Gorchakov and the American faction in Russia did not budge from their policies. The Russians, too, had their British faction surrounding the czar, but the czar and Gorchakov, like Lincoln, never wavered.

Clay fought back. Denied for the time being the ambassadorship, he used the period of his return to the United States to organize nationwide public support for the entente with Russia, and for immediate emancipation of the slaves in the United States.

Upon arriving in Washington, Clay gave Lincoln a blunt strategic briefing on the European situation:

“All over Europe governments are ready to intervene in America’s affairs and recognize the independence of the Confederate States.” Clay argued that

“only a forthright proclamation of emancipation” and alliance with Russia “will block these European autocracies.”

In a speech in the American capital, Clay began his public speaking tour for the consummation of the U.S.-Russian entente:

“I think that I can say without implications of profanity or want of deference, that since the days of Christ himself such a happy and glorious privilege has not been reserved to any other man to do that amount of good; and no man has ever more gallantly or nobly done it than Alexander II, the Czar of Russia. I refer to the emancipation of 23,000,000 serfs. Here then fellow citizens, was the place to look for an ally. Trust him; for your trust will not be misplaced. Stand by him, and he will, as he has often declared to me he will, stand by you. Not only Alexander, but his whole family are with you, men, women and children.”

Clay’s policy of utilizing the strategic options available to the Union to forestall English-French armed intervention, was readily accepted by Lincoln in both areas: movement towards emancipation, and securing the Russian alliance. Lincoln immediately commissioned Clay to sound out public opinion in his native border state of Kentucky on emancipation, before applying the policy nationally.

It was now dawning on Stanton, Seward, and the fifth column that their coup in removing Clay from the ambassadorship was backfiring. Clay, in the United States, with constant personal access to Lincoln, was a far more dangerous adversary than Clay in St. Petersburg.

Seward advised Lincoln that Clay’s speaking activities were “dangerous,” that his “unrestrained agitation for emancipation will drive Kentucky into joining the secessionist States.” Lincoln accepted this “advice” to mend shaky domestic political fences, and, as Cameron’s resignation as ambassador to Russia had just occurred, promptly reappointed Clay to his ambassadorship. Clay wrote an immediate acceptance letter to Lincoln:

“I avail myself of your kind promise to send me back to my former mission to the Court of St. Petersburg and where I flatter myself that I can better serve my country than in the field under General Halleck who cannot repress his hatred of liberal men into the ordinary courtesies of life.”

Russia saves the Union

Russia saves the Union

During Clay’s absence from St. Petersburg from June 1862 until the spring of 1863, there was no wavering of Russia’s support for the Union. Cameron arrived in St. Petersburg in June 1862 with instructions from Lincoln to secure an interview with the czar, to

“learn the Russian monarch’s attitude in the event England and France force their unwelcome intervention.” After the interview, Cameron was able to report to Lincoln: “The Czar’s spokesmen have assured me that in case of trouble with the other European powers, the friendship of Russia for the United States would be shown in a decisive manner which no other nation will be able to mistake.”

Cameron wrote the following on the Russian political situation to Secretary of State Seward in July 1862: “The Russians are evincing the most candid friendship for the North…. They are showing a constant desire to interpret everything to our advantage. There is no capital in Europe where the loyal American meets with such universal sympathy as at St. Petersburg, none where the suppression of our unnatural rebellion will be hailed with more genuine satisfaction.”

Already by the Civil War’s summer 1862 campaigns, every knowledgeable leading political figure in Europe and the United States was drawing the conclusion that foreign intervention in the American Civil War in support of the Confederacy would be taken as a casus belli by Russia.

The autumn of 1862 was extremely critical for the Union. England and France were on the verge of military intervention on the side of the Confederacy. On the Union side, everyone was girding for an Anglo-French invasion, an invasion which could include British allies Spain and Austria as well. Anglo-French pressure on Russia to abandon its pro-Union stance was stepped up to fever pitch. The Union’s salvation depended on Russia.

Lincoln, in this darkest hour of his administration, sent an urgent personal letter to Russian Foreign Minister Gorchakov for delivery to the Czar. Lincoln believed correctly that France had already decided to intervene and was only awaiting a go-ahead from England. Lincoln was under no illusions that if the Union was to be saved, it would be saved by Russia. And Russia came through.

We quote here in full Foreign Minister Gorchakov’s reply to the President, drafted in the name of Czar Alexander II. It is one of the most critical documents in American and world history:

“You know that the government of United States has few friends among the Powers. England rejoices over what is happening to you; she longs and prays for your overthrow. France is less actively hostile; her interests would be less affected by the result; but she is not unwilling to see it. She is not your friend. Your situation is getting worse and worse. The chances of preserving the Union are growing more desperate. Can nothing be done to stop this dreadful war? The hope of reunion is growing less and less, and I wish to impress upon your government that the separation, which I fear must come, will be considered by Russia as one of the greatest misfortunes. Russia alone, has stood by you from the first, and will continue to stand by you. We are very, very anxious that some means should be adopted–that any course should be pursued–which will prevent the division which now seems inevitable. One separation will be followed by another; you will break into fragments (emphasis in original).”

Bayard Taylor, secretary of the legation to St. Petersburg, acting under Lincoln’s instructions, gave the U.S. reply:

“We feel that the Northern and Southern States cannot peacefully exist side by side as separate republics. There is nothing the American people desire so much as peace, but peace on the basis of separation is equivalent to continual war. We have only just called the whole strength of the nation into action. We believe the struggle now commencing will be final, and we cannot without disgrace and ruin, accept the only terms tried and failed.”

Gorchakov reiterated Russia’s stance, giving Taylor the following message to convey to Lincoln.

“You know the sentiments of Russia. We desire above all things the maintenance of the American Union as one indivisible nation. We cannot take any part, more than we have done. We have no hostility to the Southern people. Russia has declared her position and will maintain it. There will be proposals of intervention [by Britain]. We believe that intervention could do no good at present. Proposals will be made to Russia to join some plan of interference. She will refuse any intervention of the kind. Russia will occupy the same ground as at the beginning of the struggle. You may rely upon it, she will not change.But we entreat you to settle the difficulty. I cannot express to you how profound an anxiety we feel–how serious are our fears (emphasis in original).”

How many Americans today know that Russia intervened, at this October 1862 darkest hour of the American Republic, to save it? But every American citizen knew it then, and the entire proceedings were ordered published and distributed throughout the nation by a joint resolution of Congress.

France was promoting an “armistice” plan that would have effectively stopped Lincoln’s prosecution of the war and rendered permanent the split in the Union. Britain’s Lord Russell favored the plan,

“with a view to the recognition of the independence of the Confederates. I agree further that, in case of failure, we ought to ourselves recognize the Southern States as an independent state.”

The British cabinet was now plunged into debate on whether to intervene, with all eyes and ears nervously awaiting the signal from St. Petersburg of what Russia’s response to Britain’s overtures would be. In the midst of the debate, Lord Russell received a telegram from British Ambassador Napier in St. Petersburg advising him that Russia had rejected Napoleon’s proposal of joint intervention. On Nov. 13, the British cabinet reached its decision:

“It is the cabinet’s belief that there exists no ground at the moment to hope that Lincoln’s government would accept the offer of mediation.”

We give the final word to Czar Alexander II, who held sole power to declare war for Russia. In an interview to the American banker Wharton Barker on Aug. 17, 1879, he said:

“In the Autumn of 1862, the governments of France and Great Britain proposed to Russia, in a formal but not in an official way, the joint recognition by European powers of the independence of the Confederate States of America. My immediate answer was: `I will not cooperate in such action; and I will not acquiesce. On the contrary, I shall accept the recognition of the independence of the Confederate States by France and Great Britain as a casus belli for Russia. And in order that the governments of France and Great Britain may understand that this is no idle threat; I will send a Pacific fleet to San Francisco and an Atlantic fleet to New York.

“Sealed orders to both Admirals were given. My fleets arrived at the American ports, there was no recognition of the Confederate States by Great Britain and France. The American rebellion was put down, and the great American Republic continues.

“All this I did because of love for my own dear Russia, rather than for love of the American Republic. I acted thus because I understood that Russia would have a more serious task to perform if the American Republic, with advanced industrial development were broken up and Great Britain should be left in control of most branches of modern industrial development.”

The Russian Navy arrives

The second half of 1863 and early 1864 mark the second critical phase of the Civil War period, where again the world came very close to a British-instigated eruption of global war. The second half of 1863 witnessed even more earnest British deliberations on intervening, this time on a now-or-never basis.

By July 1863, desperation gripped Lords Russell and Palmerston. The South’s invasion of the North had failed at Gettysburg. The violent anti-war movement in the North, including the bloody New York City draft riots, had also failed. As of July 4, 1863, the Union controlled the entire length of the Mississippi, cutting the Confederacy in two, while Lincoln’s naval blockade had become almost completely effective. In Russia, the British-orchestrated Polish rebellion was being extinguished. The British grand strategy of dismembering both the United States and the Russian Empire and creating the “United States of Europe” as a satrapy was crumbling into dust.

In these utterly desperate circumstances, Britain was crazy enough to go to war, and almost did. Throughout the summer of 1863, thinly disguised ultimatums were repeatedly hurled at Russia by Britain and France, and the British were deliberating on intervening against the Union.

World war almost came in the late summer and fall of 1863. The fact that it did not was not a result of British policy in and of itself, but because joint U.S.-Russian war preparations and preemptive actions raised the penalty factor to a threshold sufficient to force Britain once again to withdraw from the brink.

It was in this context that the entire Russian Navy arrived in the United States on Sept. 24, 1863.

Russia’s policy, from 1861 on, was war avoidance as long as Britain did not intervene militarily against the Union. From 1861, Russia developed a war-fighting strategy in the event Britain could not be dissuaded from intervening. One critical strategic aspect of this contingency plan concerned the deployment of the Russian fleet.

To avoid a repetition of the disaster of the Crimean War, where the fleet was bottled up and attacked in the Baltic and Black Seas, Russia’s Navy was placed on constant alert status during the United States Civil War, ready to set sail and head for the United States to join up with the United States Navy and provide a maximum combined naval capability that would be directed against the vulnerable island state of Britain. The timing of the fleet’s departure from Russian ports was decided on the basis of highly accurate Russian intelligence estimates that considered the outbreak of world war to be imminent. These estimates cohered with the fact that Britain’s propensity to go to war in late 1863 was far greater than even during the intervention proposal period of late 1862.

The fleet that came on Sept. 24, 1863 to U.S. waters–on both coasts simultaneously–came under arrangement of a U.S.-Russian political-military alliance which would become fully activated in the event of war. Cassius Clay, during his tenure as United States ambassador to Russia, spoke openly and continuously of a U.S.-Russian alliance. No ambassador, without being subject to immediate recall, could do such a thing if such an alliance did not actually exist. Russian Foreign Minister Gorchakov also announced officially, in a communication to his ambassador, Stoeckl, that the alliance existed:

“I have given much thought to the possibility of concluding a formal political alliance … but that would not change anything in the existing position of the two nations … the alliance already exists in our mutual interests and traditions.”

To this memo, dated Oct. 22, 1863, Alexander II added the comment, “très bien” (“very good”).

How the Russian Navy was built up

The actual history of U.S.-Russian military-technological collaboration, both before and during the Civil War, makes a mockery of the revisionist historians’ claim that there never was a Russian-American alliance. The origins of the modern Russian Navy itself attest to this. John Paul Jones, or “Pavel Ivanovich Jones” as he was called during his service in the Russian Navy, did not arrive in Russia in 1788 by a miracle and receive a commission as a rear admiral in Catherine the Great’s Navy. Nor was it mere chance that a document drafted by Jones in 1791, following his Russian tenure of duty, was adopted by Russia as the basis for reorganizing its fleet into a modern Navy.

From 1781 on, Princess Catherine Dashkov, the head of the Russian Academy of Sciences (of the same Dashkov family that Cassius Clay frequently cites as “my good friends” in his Memoirs), was in correspondence with Benjamin Franklin and his great-nephew and Paris secretary, Jonathan Williams–the future superintendent of West Point. Dashkov functioned then and later as a liaison channeling Franklin and Williams’s political, scientific, and military writings into the Russian Navy Ministry and the Russian Academy of Sciences, where they were promptly translated and circulated. It was through similar network arrangements among leading figures that Alexander Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures was translated and widely circulated in Russia by 1783.

In the period of Whig resurgence, beginning in the 1840s, the strong military ties connecting the United States and Russia were fashioned. It was the former U.S. Army Corps of Engineers officers who supervised the construction of Russia’s first railroad. The individuals who were to become the naval commanders of both powers during the Civil War were already committed in their own minds to the policy of entente between the two powers, based on their mutual commitment to progress, no later than the Crimean War years. In the extensive fraternization and discussion that occurred among the Mediterranean squadron commanders (Farragut, the Grand Duke Constantine, Lessovsky, and others), a powerful U.S.-Russian military alliance against Great Britain came to be viewed by the participants as a historical necessity.

After the Civil War began, the implementation of a joint U.S.-Russian naval buildup began. Long before the Russian fleet was en route to the United States, a vast stream of American military aid had already begun transforming Russia into a first-rate naval power, soon to be technologically superior to Great Britain. The abrupt transformation of backward Russia into a first-class naval power was the subject of many fear-ridden commentaries in the London Times. In 1861, Russia still had no shipbuilding facilities for ironclads. By mid-1862, Cassius Clay’s “Russian system” had not only established new shipyards capable of turning out ironclads (of the latest American designs, built to American specifications), but also the necessary metalworking, machine tool, and armaments enterprises–all with completely indigenous materials and labor force.

By the end of the Civil War, Russia had 13 ironclads, equipped with 15-inch guns, constructed from the blueprints of the U.S.S. Passaic–warships that nothing in the British Navy at the time was capable of sinking.

Abraham Lincoln and Tsar Alexander II

“God bless the Russians”

On Sept. 24, 1863, the Russian fleet dropped anchor in New York harbour. America exploded with joy. Harper’s Weekly took special pride in pointing out the American design of the ships and the armaments on board:

“The two largest of the squadron, the frigates Alexander Nevsky and Peresvet, are evidently vessels of modern build, and much about them would lead an un-practiced eye to think they were built in this country…. The flagship’s guns are of American make, being cast in Pittsburgh.”

New York City was “gaily bedecked with American Russian flags,” the fleet’s officers were given a special parade with a United States military honor guard escorting them up Broadway past cheering crowds.

British newspapers began an angry howl, denouncing “Lincoln’s threats of war” against Britain and launching a press campaign “poking fun” at the “Americans, who have been hoodwinked by the Russians.”

Harper’s Weekly ran an editorial in reply to this English psychological warfare campaign which expressed the prevailing consensus in the United States:

“John Bull thinks that we are absurdly bamboozled by the Russian compliments and laughs to see us deceived by the sympathy of Muscovy…. But we are not very much deceived. Americans understand that the sympathy of France in our Revolution for us was not for love of us, but from hatred of England. They know, as Washington long ago told them, that romantic friendship between nations is not to be expected. And if they had latterly expected it, England has utterly undeceived them.

“Americans do not suppose that Russia is on the point of becoming a Republic, but they observe that the English aristocracy and the French Empire hate a republic quite as much as the Russian monarchy hates it; and they remark that while the French Empire imports coolies into its colonies, and winks at slavery, and while the British government cheers a political enterprise founded upon slavery, and by its chief organs defends the system, Russia emancipates her serfs. There is not the least harm in observing these little facts. Russia, John Bull will remember, conducts herself as a friendly power. That is all. England and France have shown themselves to be unfriendly powers. And we do not forget it.”

The Russian fleet was to remain in United States waters for seven months, departing in April 1864 only after both Russia and the United States had fully satisfied themselves that all danger of war from Europe had passed. Throughout the stay there were continuous celebrations, festivities, and a daily public outpouring of American gratitude. The Russian ships stationed off New York sailed in December for Washington, and made their way up the Potomac River, dropping anchor at the nation’s capital. This commenced another round of celebrations. With the unfortunate exception of Lincoln, who at the time was suffering a mild case of smallpox, the entire cabinet and Mrs. Lincoln hosted the Russian officers at gala receptions on board the flagship. The Russians toasted Lincoln, and Mrs. Lincoln led a toast to the czar and the emancipation of the serfs.

A two-power, two-ocean Navy

The Russian Pacific fleet’s stay in San Francisco was also filled with celebrations, and provides further evidence of how detailed were the plans which had been worked out for the alliance.

During the Civil War, the United States had only a one-ocean navy, and it patrolled the East Coast while the Pacific Coast remained unprotected by U.S. naval forces. Under these conditions, the Russian fleet at San Francisco filled the wartime function of a U.S. Pacific fleet. Recall here the testimony of American Admiral Farragut and Russian Atlantic fleet commander, Admiral Lessovsky, corroborating the czar’s reference to the existence of sealed orders for the Russian fleet’s intervention on the side of the Union should England or her allies attack Lincoln’s government.

We now cite the testimony of Pacific fleet commander Popov to establish the case that not only the Russian fleet in the Atlantic, but the czar’s Pacific fleet, as well, was under such orders.

In the winter of 1863-64, rumors swept San Francisco that an attack by the Confederate raiders Alabamaand Sumter was imminent. The California government appealed to Admiral Popov for protection. Popov’s reply, citing his orders for the contingency of a British or a Confederate naval attack on the West Coast, demonstrates beyond a doubt that London’s continuous denunciations of a “secret alliance” between Russia and the United States during the Civil War period were based on reality:

“Should a Southern cruiser attempt an assault … we shall put on steam and clear for action…. The ships of his Imperial Majesty are bound to assist the authorities of every place where friendship is offered them, in all measures which may be deemed necessary by the local authorities, to repel any attempt against the security of the place.”

The United States West Coast was never attacked.

The postwar outlook

The central determinant of world politics through the period from 1863 to 1867 was the drive of American Whigs and the Russian government to consolidate their wartime alliance into a permanent entente. Throughout the 1860s, American and Russian “Whigs” continuously pushed to secure this permanent alliance, even, in the American case, under the enormous handicaps that emerged after Lincoln’s assassination.

At the height of the celebration that engulfed the United States following the arrival of the Russian Fleet, on Oct. 17, 1863, Harper’s Weekly ran an editorial which expressed the nation’s dominant public sentiment. The editorial called for a permanent alliance with Russia, as the international strategic anchor to guarantee world peace and economic development for decades to come. This document speaks eloquently for itself:

“It seems quite doubtful, under these circumstances, whether we can possibly much longer maintain the position of proud isolation which Washington coveted….

“The alliance of the Western Powers [Britain and France], maintained through the Crimean War and exemplified in the recognition of the Southern rebels by both powers conjointly–is in fact, if not in name, a hostile combination against the United States.

“What is our proper reply to this hostile combination?|… Would it not be wise to meet the hostile alliance by an alliance with Russia? France and England united can do and dare much against Russia alone or the United States alone; but against Russia and the United States combined what could they do?

“The analogies between the American and Russian people have too often been described to need further explanation here. Russia, like the United States, is a nation of the future. Its capabilities are only just being developed. Its national destiny is barely shaped. Its very institutions are in their cradle, and have yet to be modeled to fit advancing civilization and the spread of intelligence. Russia is in the agonies of a terrible transition: the Russian serfs like the American Negroes, are receiving their liberty; and the Russian boiars, like the Southern slaveowners, are mutinous at the loss of their property. When this great problem shall have been solved, and the Russian people shall consist of 100,000,000 intelligent, educated beings, it is possible that Russian institutions will have been welded by the force of civilization into a similarity with ours. At that period, the United States will probably also contain 100,000,000 educated, intelligent people. Two such peoples, firmly bound together by an alliance as well as by traditional sympathy and good feeling, what would be impossible? Certainly the least of the purposes which they could achieve would be to keep the peace of the world….

“At the present time Russia and the United States occupy remarkably similar positions. A portion of the subjects of the Russian Empire, residing in Poland, have attempted to secede and set up an independent national existence, just as our Southern slaveowners have tried to secede from the Union and set up a slave Confederacy; and the Czar, like the government of the Union, has undertaken to put down the insurrection by force of arms. In that undertaking, which every government is bound to make under penalty of national suicide, Russia, like the United States has been thwarted and annoyed by the interference of France and England. The Czar, like Mr. Lincoln, nevertheless, perseveres in his purpose; and being perfectly in earnest and determined, has sent a fleet into our waters in order that, if war should occur, British and French commerce should not escape as cheaply as they did during the Crimean contest.

“An alliance between Russia and the United States at the present time would probably relieve both of us from all apprehensions of foreign interference. It is not likely it would involve either nation in war. On the contrary, it would probably be the best possible guarantee against war. It would be highly popular in both countries….

“The reception given last week in this city to Admiral Lisovski [Lessovsky] and his officers will create more apprehension at the Tuilleries and at St. James than even the Parrott gun or the capture of the Atlanta. If it be followed up by diplomatic negotiations, with a view to an alliance with the Czar, it may prove an epoch of no mean importance in history.”

The end of the entente

The fact that such a post-Civil War epoch of peace and development, based on a formal “superpowers” entente, did not materialize, requires no long-winded explanation. Lincoln’s assassination by a British conspiracy cost the United States Whigs the Executive. After Lincoln’s death, the White House and the cabinet fell under the sway of British agents of influence, sealing the fate of the entente.

A year and a day following Lincoln’s death, on April 16, 1866, the czar narrowly escaped assassination. This galvanized the American Whigs into action. The Republican congressional leadership drafted a resolution, which was overwhelmingly passed by Congress, authorizing the dispatch of a special envoy to Russia “to convey in person to His Imperial Majesty America’s good will and congratulations to the twenty millions of serfs upon the providential escape from danger of the Sovereign to whose head and heart they owe the blessings of their freedom.”

Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Vasa Fox was selected to head the mission. On Aug. 8, 1866, Fox, accompanied by Ambassador Clay, formally presented the joint resolution of the Congress to Alexander II, with Russian Foreign Minister Gorchakov standing in attendance. The American delegation went on a national tour, with entertainment, fireworks, and parades everywhere.

The U.S. delegation’s tour marked the post-war high-water mark of the entente. After late 1866, the cabinet of the Johnson administration, under Secretary of State Seward’s direction, successfully implemented a containment strategy against the Whig goals. The British consolidated their position in Canada, one step in reestablishing British imperial hegemony on a global scale. The consolidation included the murder of Alexander II at the hands of a British-deployed assassin in March 1881.

Humanity, then, came very close to securing the world for global industrial development, with a United States-Russian entente as its strategic core. The prospects for entente and the objective capability of a United States-Russian alliance to finish off the City of London exist today. We dare not fail a second time.