The CIA/MSM Contra-Cocaine Cover-up

By Robert Parry

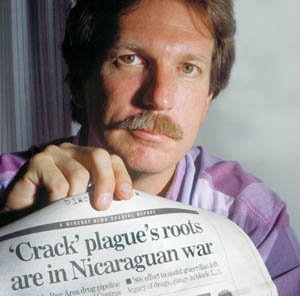

Exclusive: With Hollywood set to release a movie about the Contra-cocaine scandal and the destruction of journalist Gary Webb, an internal CIA report has surfaced showing how the spy agency manipulated the mainstream media’s coverage to disparage Webb and contain the scandal, reports Robert Parry.

By Robert Parry

In 1996 – as major U.S. news outlets disparaged the Nicaraguan Contra-cocaine story and destroyed the career of investigative reporter Gary Webb for reviving it – the CIA marveled at the success of its public-relations team guiding the mainstream media’s hostility toward both the story and Webb, according to a newly released internal report.

Entitled “Managing a Nightmare: CIA Public Affairs and the Drug Conspiracy Story,” the six-page report describes the CIA’s damage control after Webb’s “Dark Alliance” series was published in the San Jose Mercury-News in August 1996. Webb had resurrected disclosures from the 1980s about the CIA-backed Contras collaborating with cocaine traffickers as the Reagan administration worked to conceal the crimes.

Although the CIA’s inspector general later corroborated the truth about the Contra-cocaine connection and the Reagan administration’s cover-up, the mainstream media’s counterattack in defense of the CIA in late summer and fall of 1996 proved so effective that the subsequent CIA confession made little dent in the conventional wisdom regarding either the Contra-cocaine scandal or Gary Webb.

In fall 1998, when the CIA inspector general’s extraordinary findings were released, the major U.S. news media largely ignored them, leaving Webb a “disgraced” journalist who – unable to find a decent-paying job in his profession – committed suicide in 2004, a dark tale that will be revisited in a new movie, “Kill the Messenger,” starring Jeremy Renner and scheduled to reach theaters on Oct. 10.

The “Managing a Nightmare” report offers something of the CIA’s back story for how the spy agency’s PR team exploited relationships with mainstream journalists who then essentially did the CIA’s work for it, mounting a devastating counterattack against Webb that marginalized him and painted the Contra-cocaine trafficking story as some baseless conspiracy theory.

Crucial to that success, the report credits “a ground base of already productive relations with journalists and an effective response by the Director of Central Intelligence’s Public Affairs Staff [that] helped prevent this story from becoming an unmitigated disaster.

“This success has to be viewed in relative terms. In the world of public relations, as in war, avoiding a rout in the face of hostile multitudes can be considered a success. … By anyone’s definition, the emergence of this story posed a genuine public relations crisis for the Agency.” [As approved for release by the CIA last July 29, the report’s author was redacted as classified, however, Ryan Devereaux of The Intercept identified the writer as former Directorate of Intelligence staffer Nicholas Dujmovic.]

According to the CIA report, the public affairs staff convinced some journalists who followed up Webb’s exposé by calling the CIA that “this series represented no real news, in that similar charges were made in the 1980s and were investigated by the Congress and were found to be without substance. Reporters were encouraged to read the ‘Dark Alliance’ series closely and with a critical eye to what allegations could actually be backed with evidence. Early in the life of this story, one major news affiliate, after speaking with a CIA media spokesman, decided not to run the story.”

Of course, the CIA’s assertion that the Contra-cocaine charges had been disproved in the 1980s was false. In fact, after Brian Barger and I wrote the first article about the Contra-cocaine scandal for the Associated Press in December 1985, a Senate investigation headed by Sen. John Kerry confirmed that many of the Contra forces were linked to cocaine traffickers and that the Reagan administration had even contracted with drug-connected airlines to fly supplies to the Contras who were fighting Nicaragua’s leftist Sandinista government.

However, in the late 1980s, the Reagan administration and the CIA had considerable success steering the New York Times, the Washington Post and other major news outlets away from the politically devastating reality that President Ronald Reagan’s beloved Contras were tied up with cocaine traffickers. Kerry’s groundbreaking report – when issued in 1989 – was largely ignored or mocked by the mainstream media.

That earlier media response left the CIA’s PR office free to cite the established “group think” – rather than the truth — when beating back Webb’s resurfacing of the scandal in 1996.

A ‘Firestorm’ of Attacks

The initial attacks on Webb’s series came from the right-wing media, such as the Washington Times and the Weekly Standard, but the CIA’s report identified the key turning point as coming when the Washington Post pummeled Webb in two influential articles.

The CIA’s PR experts quickly exploited that opening. The CIA’s internal report said: “Public Affairs made sure that reporters and news directors calling for information – as well as former Agency officials, who were themselves representing the Agency in interviews with the media – received copies of these more balanced stories. Because of the Post’s national reputation, its articles especially were picked up by other papers, helping to create what the Associated Press called a ‘firestorm of reaction’ against the San Jose Mercury-News.”

The CIA’s report then noted the happy news that Webb’s editors at the Mercury-News began scurrying for cover, “conceding the paper might have done some things differently.” The retreat soon became a rout with some mainstream journalists essentially begging the CIA for forgiveness for ever doubting its innocence.

“One reporter of a major regional newspaper told [CIA] Public Affairs that, because it had reprinted the Mercury-News stories in their entirety, his paper now had ‘egg on its face,’ in light of what other newspapers were saying,” the CIA’s report noted, as its PR team kept track of the successful counterattack.

“By the end of September [1996], the number of observed stories in the print media that indicated skepticism of the Mercury-News series surpassed that of the negative coverage, which had already peaked,” the report said. “The observed number of skeptical treatments of the alleged CIA connection grew until it more than tripled the coverage that gave credibility to that connection. The growth in balanced reporting was largely due to the criticisms of the San Jose Mercury-News by The Washington Post, The New York Times, and especially The Los Angeles Times.”

The overall tone of the CIA’s internal assessment is one of almost amazement at how its PR team could, with a deft touch, help convince mainstream U.S. journalists to trash a fellow reporter on a story that put the CIA in a negative light.

“What CIA media spokesmen can do, as this case demonstrates, is to work with journalists who are already disposed toward writing a balanced story,” the report said. “What gives this limited influence a ‘multiplier effect’ is something that surprised me about the media: that the journalistic profession has the will and the ability to hold its own members to certain standards.”

The report then praises the neoconservative American Journalism Review for largely sealing Webb’s fate with a harsh critique entitled “The Web That Gary Spun,” with AJR’s editor adding that the Mercury-News “deserved all the heat leveled at it for ‘Dark Alliance.’”

The report also cites with some pleasure the judgment of the Washington Post’s media critic Howard Kurtz who reacted to Webb’s observation that the war was a business to some Contra leaders with the snide comment: “Oliver Stone, check your voice mail.”

Neither Kurtz nor the CIA writer apparently was aware of the disclosure — among Iran-Contra documents — of a March 17, 1986 message about the Contra leadership from White House aide Oliver North’s emissary to the Contras, Robert Owen, who complained to North: “Few of the so-called leaders of the movement . . . really care about the boys in the field. … THIS WAR HAS BECOME A BUSINESS TO MANY OF THEM.” [Emphasis in original.]

Misguided Group Think

Yet, faced with this mainstream “group think” – as misguided as it was – Webb’s Mercury-News editors surrendered to the pressure, apologizing for the series, shutting down the newspaper’s continuing investigation into the Contra-cocaine scandal and forcing Webb to resign in disgrace.

But Webb’s painful experience provided an important gift to American history, at least for those who aren’t enamored of superficial “conventional wisdom.” CIA Inspector General Frederick Hitz ultimately produced a fairly honest and comprehensive report that not only confirmed many of the longstanding allegations about Contra-cocaine trafficking but revealed that the CIA and the Reagan administration knew much more about the criminal activity than any of us outsiders did.

Hitz completed his investigation in mid-1998 and the second volume of his two-volume investigation was published on Oct. 8, 1998. In the report, Hitz identified more than 50 Contras and Contra-related entities implicated in the drug trade. He also detailed how the Reagan administration had protected these drug operations and frustrated federal investigations throughout the 1980s.

According to Volume Two, the CIA knew the criminal nature of its Contra clients from the start of the war against Nicaragua’s leftist Sandinista government. The earliest Contra force, called the Nicaraguan Revolutionary Democratic Alliance (ADREN) or the 15th of September Legion, had chosen “to stoop to criminal activities in order to feed and clothe their cadre,” according to a June 1981 draft of a CIA field report.

According to a September 1981 cable to CIA headquarters, two ADREN members made the first delivery of drugs to Miami in July 1981. ADREN’s leaders included Enrique Bermúdez and other early Contras who would later direct the major Contra army, the CIA-organized FDN. Throughout the war, Bermúdez remained the top Contra military commander.

The CIA corroborated the allegations about ADREN’s cocaine trafficking, but insisted that Bermúdez had opposed the drug shipments to the United States that went ahead nonetheless. The truth about Bermúdez’s supposed objections to drug trafficking, however, was less clear.

According to Hitz’s Volume One, Bermúdez enlisted Norwin Meneses, a large-scale Nicaraguan cocaine smuggler and a key figure in Webb’s series, to raise money and buy supplies for the Contras.Volume One had quoted a Meneses associate, another Nicaraguan trafficker named Danilo Blandón, who told Hitz’s investigators that he and Meneses flew to Honduras to meet with Bermúdez in 1982. At the time, Meneses’s criminal activities were well-known in the Nicaraguan exile community. But Bermúdez told these cocaine smugglers that “the ends justify the means” in raising money for the Contras.

After the Bermúdez meeting, Contra soldiers helped Meneses and Blandón get past Honduran police who briefly arrested them on drug-trafficking suspicions. After their release, Blandón and Meneses traveled on to Bolivia to complete a cocaine transaction.

There were other indications of Bermúdez’s drug-smuggling tolerance. In February 1988, another Nicaraguan exile linked to the drug trade accused Bermúdez of participation in narcotics trafficking, according to Hitz’s report. After the Contra war ended, Bermúdez returned to Managua, Nicaragua, where he was shot to death on Feb. 16, 1991. The murder has never been solved. [For more details on Hitz’s report and the Contra-cocaine scandal, see Robert Parry’s Lost History.]

Shrinking Fig Leaf

By the time that Hitz’s Volume Two was published in fall 1998, the CIA’s defense against Webb’s series had shrunk to a fig leaf: that the CIA did not conspire with the Contras to raise money through cocaine trafficking. But Hitz made clear that the Contra war took precedence over law enforcement and that the CIA withheld evidence of Contra crimes from the Justice Department, Congress and even the CIA’s own analytical division.

Besides tracing the evidence of Contra-drug trafficking through the decade-long Contra war, the inspector general interviewed senior CIA officers who acknowledged that they were aware of the Contra-drug problem but didn’t want its exposure to undermine the struggle to overthrow Nicaragua’s Sandinista government.

According to Hitz, the CIA had “one overriding priority: to oust the Sandinista government. . . . [CIA officers] were determined that the various difficulties they encountered not be allowed to prevent effective implementation of the Contra program.” One CIA field officer explained, “The focus was to get the job done, get the support and win the war.”

Hitz also recounted complaints from CIA analysts that CIA operations officers handling the Contras hid evidence of Contra-drug trafficking even from the CIA’s analysts.

Because of the withheld evidence, the CIA analysts incorrectly concluded in the mid-1980s that “only a handful of Contras might have been involved in drug trafficking.” That false assessment was passed on to Congress and to major news organizations — serving as an important basis for denouncing Gary Webb and his “Dark Alliance” series in 1996.

Although Hitz’s report was an extraordinary admission of institutional guilt by the CIA, it went almost unnoticed by major U.S. news outlets. By fall 1998, the U.S. mainstream media was obsessed with President Bill Clinton’s Monica Lewinsky sex scandal. So, few readers of major U.S. newspapers saw much about the CIA’s inspector general admitting that America’s premier spy agency had collaborated with and protected cocaine traffickers.

On Oct. 10, 1998, two days after Hitz’s Volume Two was posted on the CIA’s Web site, the New York Times published a brief article that continued to deride Webb but acknowledged the Contra-drug problem may have been worse than earlier understood. Several weeks later, the Washington Post weighed in with a similarly superficial article. The Los Angeles Times, which had assigned a huge team of 17 reporters to tear down Webb’s work, never published a story on the release of Hitz’sVolume Two.

In 2000, the Republican-controlled House Intelligence Committee grudgingly acknowledged that the stories about Reagan’s CIA protecting Contra drug traffickers were true. The committee released a report citing classified testimony from CIA Inspector General Britt Snider (Hitz’s successor) admitting that the spy agency had turned a blind eye to evidence of Contra-drug smuggling and generally treated drug smuggling through Central America as a low priority.

“In the end the objective of unseating the Sandinistas appears to have taken precedence over dealing properly with potentially serious allegations against those with whom the agency was working,” Snider said, adding that the CIA did not treat the drug allegations in “a consistent, reasoned or justifiable manner.”

The House committee still downplayed the significance of the Contra-cocaine scandal, but the panel acknowledged, deep inside its report, that in some cases, “CIA employees did nothing to verify or disprove drug trafficking information, even when they had the opportunity to do so. In some of these, receipt of a drug allegation appeared to provoke no specific response, and business went on as usual.”

Like the release of Hitz’s report in 1998, the admissions by Snider and the House committee drew virtually no media attention in 2000 — except for a few articles on the Internet, including one at Consortiumnews.com.

Killing the Messenger

Because of this abuse of power by the Big Three newspapers — choosing to conceal their own journalistic negligence on the Contra-cocaine scandal and to protect the Reagan administration’s image — Webb’s reputation was never rehabilitated.

After his original “Dark Alliance” series was published in 1996, I joined Webb in a few speaking appearances on the West Coast, including one packed book talk at the Midnight Special bookstore in Santa Monica, California. For a time, Webb was treated as a celebrity on the American Left, but that gradually faded.

In our interactions during these joint appearances, I found Webb to be a regular guy who seemed to be holding up fairly well under the terrible pressure. He had landed an investigative job with a California state legislative committee. He also felt some measure of vindication when CIA Inspector General Hitz’s reports came out.

However, Webb never could overcome the pain caused by his betrayal at the hands of his journalistic colleagues, his peers. In the years that followed, Webb was unable to find decent-paying work in his profession — the conventional wisdom remained that he had somehow been exposed as a journalistic fraud. His state job ended; his marriage fell apart; he struggled to pay bills; and he was faced with a forced move out of a just-sold house near Sacramento, California, and in with his mother.

On Dec. 9, 2004, the 49-year-old Webb typed out suicide notes to his ex-wife and his three children; laid out a certificate for his cremation; and taped a note on the door telling movers — who were coming the next morning — to instead call 911. Webb then took out his father’s pistol and shot himself in the head. The first shot was not lethal, so he fired once more.

Even with Webb’s death, the big newspapers that had played key roles in his destruction couldn’t bring themselves to show Webb any mercy. After Webb’s body was found, I received a call from a reporter for the Los Angeles Times who knew that I was one of Webb’s few journalistic colleagues who had defended him and his work.

I told the reporter that American history owed a great debt to Gary Webb because he had forced out important facts about Reagan-era crimes. But I added that the Los Angeles Times would be hard-pressed to write an honest obituary because the newspaper had not published a single word on the contents of Hitz’s final report, which had largely vindicated Webb.

To my disappointment but not my surprise, I was correct. The Los Angeles Times ran a mean-spirited obituary that made no mention of either my defense of Webb or the CIA’s admissions in 1998. The obituary – more fitting for a deceased mob boss than a fellow journalist – was republished in other newspapers, including the Washington Post.

In effect, Webb’s suicide enabled senior editors at the Big Three newspapers to breathe a little easier — one of the few people who understood the ugly story of the Reagan administration’s cover-up of the Contra-cocaine scandal and the U.S. media’s complicity was now silenced.

No Accountability

To this day, none of the journalists or media critics who participated in the destruction of Gary Webb has paid a price for their actions. None has faced the sort of humiliation that Webb had to endure. None had to experience that special pain of standing up for what is best in the profession of journalism — taking on a difficult story that seeks to hold powerful people accountable for serious crimes — and then being vilified by your own colleagues, the people that you expected to understand and appreciate what you had done.

In May 2013, one of the Los Angeles Times reporters who had joined in the orchestrated destruction of Webb’s career acknowledged that the newspaper’s assault was a “tawdry exercise” amounting to “overkill,” which later contributed to Webb’s suicide. This limited apology by former Los Angeles Times reporter Jesse Katz was made during a radio interview and came as filming was about to start on “Kill the Messenger,” based on a book by the same name by Nick Schou.

On KPCC-FM 89.3′s AirTalk With Larry Mantle, Katz was pressed by callers to address his role in the destruction of Webb. Katz offered what could be viewed as a limited apology.

“As an L.A. Times reporter, we saw this series in the San Jose Mercury News and kind of wonder[ed] how legit it was and kind of put it under a microscope,” Katz said. “And we did it in a way that most of us who were involved in it, I think, would look back on that and say it was overkill. We had this huge team of people at the L.A. Times and kind of piled on to one lone muckraker up in Northern California.”

Katz added, “We really didn’t do anything to advance his work or illuminate much to the story, and it was a really kind of a tawdry exercise. … And it ruined that reporter’s career.”

Now, with the imminent release of a major Hollywood movie about Webb’s ordeal, the next question is whether the major newspapers will finally admit their longstanding complicity in the Contra-cocaine cover-up or whether they will simply join the CIA’s press office in another counterattack.