Arctic Methane Emissions ‘Certain to Trigger Warming’

By Bobby Magill

Climate Central

As climate change melts Arctic permafrost and releases large amounts of methane into the atmosphere, it is creating a feedback loop that is “certain to trigger additional warming,” according to the lead scientist of a new study investigating Arctic methane emissions.

The study released this week examined 71 wetlands across the globe and found that melting permafrost is creating wetlands known as fens, which are unexpectedly emitting large quantities of methane. Over a 100-year timeframe, methane is about 35 times as potent as a climate change-driving greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, and over 20 years, it’s 84 times more potent.

Permafrost terraces in Alaska. Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildife Service Alaska/flickr

Permafrost terraces in Alaska. Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildife Service Alaska/flickr

Methane emissions come from agriculture, fossil fuel production and microbes in wetland soils, among other sources. The study says scientists have assumed that methane emissions from wetlands are high in the tropics, but not necessarily in the Arctic because of the cold temperatures there.

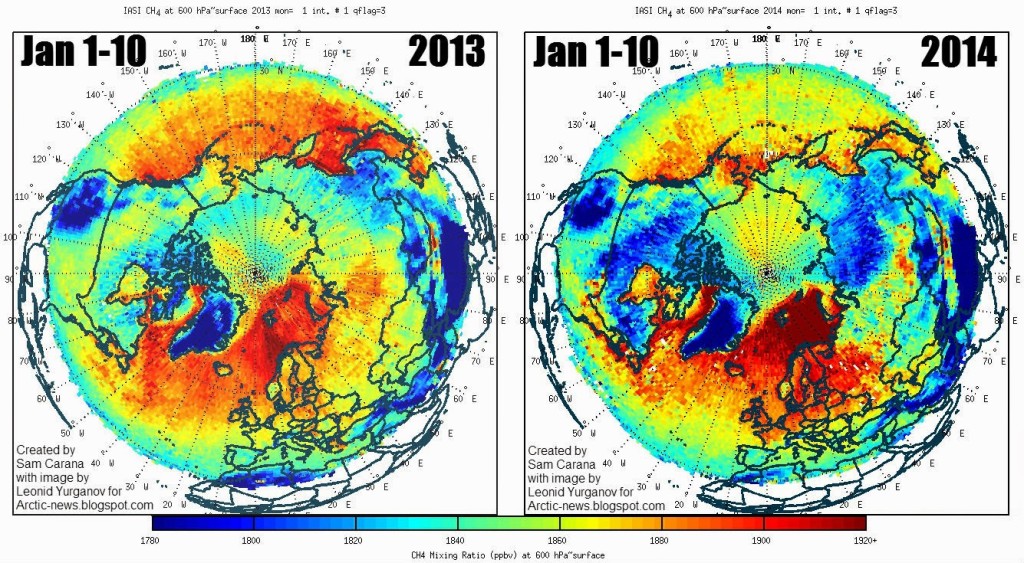

But a spike in global methane concentrations in the atmosphere seen since 2007 can be partly traced back to the formation of fens in areas where permafrost once existed, according to the study, led by University of Guelph (Ontario, Canada) biology professor Merritt Turetsky.

The methane emissions stemming from melting permafrost could be critical to determining how fast the climate will change in the future.

“Methane emissions are one example of a positive feedback between ecosystems and the climate system,” Turetsky said. “The permafrost carbon feedback is one of the important and likely consequences of climate change, and it is certain to trigger additional warming.”

Warming and thawing permafrost stimulate methane release, which enhances the greenhouse effect, creating a feedback loop, she said.

“Even if we ceased all human emissions, permafrost would continue to thaw and release carbon into the atmosphere,” Turetsky said. “Instead of reducing emissions, we currently are on track with the most dire scenario considered by the IPCC. There is no way to capture emissions from thawing permafrost as this carbon is released from soils across large regions of land in very remote spaces.”

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projected in its fifth assessment on climate change report that the earth’s average temperatures could warm by as much as 8.64°F above 1986-2005 temperatures if nothing is done to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

Coastal erosion reveals the ice-rich permafrost underlying the Arctic Coastal Plain in the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska. Credit: USGS

Coastal erosion reveals the ice-rich permafrost underlying the Arctic Coastal Plain in the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska. Credit: USGS

Turetsky’s study shows that fens in the northern latitudes created when permafrost thaws can have emissions similar to wetlands in the tropics. Emissions from fens are generally higher than bogs and some other wetland types because fens, fed by groundwater, have higher nutrient levels and more grasses than bogs, leading to more methane production.

“Our study highlights that northern wetlands without permafrost emit more methane than wetlands with permafrost,” U.S. Geological Survey research ecologist and study co-author Kimberly Wickland said.

“When permafrost is absent, wetlands can be more connected to groundwater, allowing for wetter conditions — the main ingredient for methane production,” she said. “It is possible that methane emissions from wetlands will continue to increase with continued permafrost thaw, but that will depend primarily on whether wetlands stay wet. If they dry, then methane emissions will decline.”

Gavin Schmidt, a climate scientist at NASA’s Goodard Institute for Space Studies in New York and not part of the study, said it’s too soon to draw conclusions about how much wetland methane emissions will impact global warming, though scientists widely agree that the amplified feedback is generally going to increase.

The paleo record shows that the Arctic was several degrees warmer during the last interglacial period 120,000 years ago, and there is no evidence of increased levels of methane in the atmosphere during that period, he said.

“It’s not to say at some point it won’t become an issue,” Schmidt said, adding that there is evidence of many “methane burps” across the globe in the very distant past.

“The planet is very capable of surprising us,” he said.

By surveying many wetland sites across the globe as Turetsky and her team have, scientists can gain a much broader understanding of the source of methane emissions from melting permafrost and their role in the feedback loop, Schmidt said. Many previous studies have examined just a single site whereas Turetsky’s team examined numerous sites across the globe.

“The work these people are doing in terms of trying to synthesize that information and bring it all together, I think it’s certainly going in the right direction,” he said.

Turetsky’s study, “A synthesis of methane emissions from 71 northern, temperate, and subtropical wetlands,” was published this week in the journal Global Change Biology.